The ‘new normal’ of lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic has forced clinical psychologists to adapt their practice. Online therapy is not new; E-therapy started in the 1990s as the Internet became increasingly common. There is a wealth of evidence for the power and potential of this medium in delivering therapies for mental health problems. However, there is still a need for more research to understand how best to implement remote delivery of therapy, and maximise engagement and effectiveness. An overview of useful recent literature, mostly reviews, on remote delivery for common mental health disorders is included at the end of this document (table 1).

The state of the world today, though, presents mental health practitioners with extra challenges. We need not only to conduct online therapy, but to do so taking into consideration the context and consequences of the ongoing pandemic.

The primary papers discussed in this blog are a series of resources produced by a team of clinical and experimental psychologists at the Oxford Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma (OxCADAT) at the University of Oxford.

Online psychological therapy has been proven to be effective and feasible.

Methods

The guidelines drawn up by the OxCADAT team are specifically for how to practice online. They generally assume that the reader will be an experienced C(B)T practitioner already. The team has extensive experience in clinical psychology practice and research, and literature references to support (face-to-face) CT practice are provided on the OxCADAT website. The methodology behind how the guidelines were developed is not discussed in detail.

Results

The OxCADAT group has published remote delivery guides on their website for conducting online therapy for social anxiety, panic disorder, memory work for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and cognitive therapy for PTSD after intensive care (one document for therapists and one document tailored to health care professionals). Two additional documents are available that provide information on evidence-based tools to support NHS frontline staff.

At the time of writing a video demonstration is available showing an example session for social anxiety, with the promise that additional videos will be added later. The video includes tips such as the use of shared screen to draw up a formulation or to write a thought record with the client.

The focus appears to be on cognitive therapy, leaving out the ‘behavioural’ component of CBT, although behavioural experiments are included: template forms are available, and an example is given of how to conduct behavioural experiments online, in the video demonstration.

The documents contain practical information and points to look out for while conducting cognitive therapy for specific disorders, and include links to relevant resources and templates. They offer solutions for questions that the reader may have regarding their practice, and the OxCADAT team give pointers for aspects of practice that may need special attention (e.g. a lack of observable cues, such that the therapist may need to ask more questions and more specific questions). For panic disorder, the link with COVID-19 symptoms of breathlessness is mentioned which is certainly something to watch out for.

The OxCADAT remote delivery guides will help therapists who are providing online support for people with PTSD, social anxiety and panic disorder.

Conclusions

Practical guidance for online cognitive therapy is timely and needed. The tips from the OxCADAT team can help practitioners as they migrate their current practice for panic, social anxiety and trauma symptoms, into an online setting.

Strengths, limitations, and recommendations

The OxCADAT guidelines are a welcome and useful support for therapists in their online practice. However, little is thus far known about interventions that have been developed to address the specific psychological needs that have arisen from current challenges posed by COVID-19.

The pandemic has triggered an outpouring of online guidance on how to improve mental health and well-being and increase resilience; by government, charities, and mental health organisations for example. These may be useful to help prevent or reduce mental health symptoms, but may not be sufficient to treat them. Guidelines for mental health mostly cover two types of interventions: general prevention and resilience building, and the translation of clinical practice to an online environment.

Even though individual circumstances are always taken into account when drawing up a CBT formulation with a client, it is vital to emphasise the overall context and effects of the pandemic more specifically. We cannot treat clinical practice as ‘business as usual’ in these unprecedented and uncertain times.

We cannot treat clinical practice as ‘business as usual’ in these unprecedented and uncertain times.

Treating mental health problems during pandemics

So, what is known about evidence for treating mental health symptoms during pandemics? Not much. Guidelines to improve mental health during COVID-19 have been drawn up speedily, but results have not yet been tested and analysed.

However, some evidence from Psychological and Emergency First Aid is available that may be relevant and helpful to illustrate what combination of approaches would be best suited.

Psychological first aid

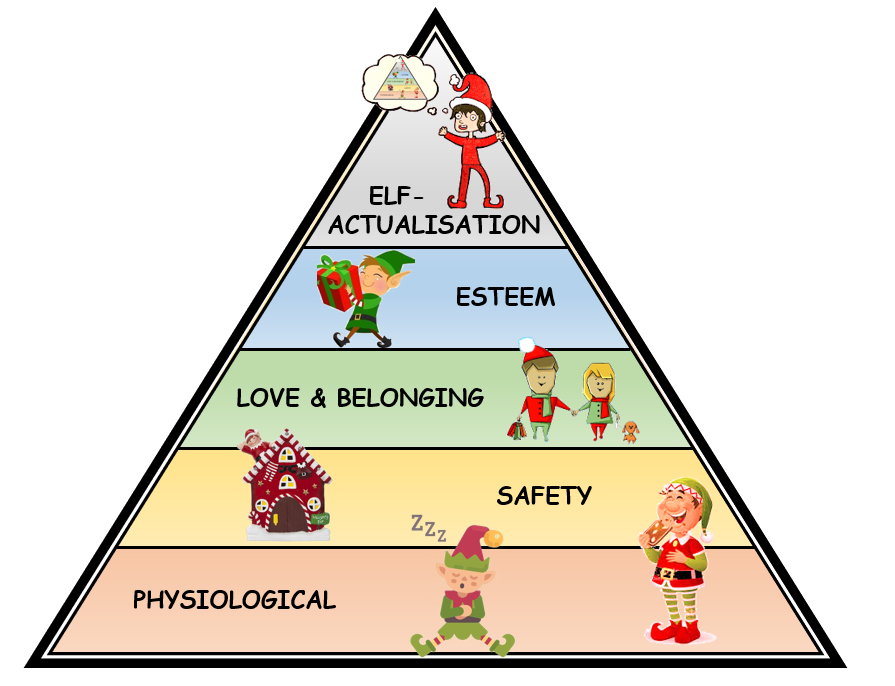

Psychological First Aid has been proven effective and is an obvious candidate to be incorporated into clinical practice in these times (see the book authored by Everly & Lating (2017) for an overview and guidance). Maslow’s (1946) pyramid of needs, long forgotten except for in Psychology 101 books in the Western world, is not only relevant in developing countries or disaster-ridden areas, but here holds the key to understanding how to intervene at the right level.

Food

Right now, even basic physiological needs may be in danger. Besides the obvious immediate risks to health, the pandemic may have caused people to experience financial hardship due to job loss; food may not be as accessible especially for the elderly and vulnerable who have been forced to isolate; and for those in dire need, school meals may not be available. Moreover, even though food may be available to an individual, the growing awareness of vulnerabilities in the supply chain and the precariousness of day-to-day life may well lead to formerly unknown feelings of unease.

Safety, grief and powerlessness

At the second level, safety (or at least sense of safety) is endangered for all of us. This is especially true for workers who have jobs that force them to go out and mingle with others, those working frontline jobs with COVID-19 patients, the elderly and vulnerable, and for those who live with others that are not self-isolating. At the third level, some people may be unable to afford reliable internet access, interfering with their capability to connect with others. The isolation resulting from lockdown may be felt even more strongly in those who live alone, and must not be underestimated (Armitage & Nellum, 2020). Some may have lost loved ones, and in these days, grief may be even more distressing because of the inability to connect in those final days, and not having been able to say goodbye due to the forced social distancing and at a later stage, limitations on funeral services. For healthcare staff the picture is similarly bleak: they suffer long hours, changes in work place and disruption to schedules, possibly having to live away from home, and prolonged exposure to excruciating events unfolding and in many cases being powerless to save lives.

Uncertainty

Even when physiological, safety, and belonging needs are still met, the internet is working, and one still has their job, food is on the table (thanks to stocking up for Brexit), daily and family life has been changed dramatically, posing its own challenges with consequences for all of us, and on all of Maslow’s levels. We all want to know when life will be back to normal, but there remains a great uncertainty over when and how the lockdown will be lifted, and what remaining measures of social distancing will still be in place. Uncertainty has been identified as a major stressor, and poses a risk factor in the development of mental health disorders (Wu et al., 2020). And even when some day in the near future life is functioning again, it may be in a different job, without some of our favourite shops and restaurants, and without our loved ones. Though it can be reassuring and be helpful to try to live our lives as before as much as possible, we can’t by any means pretend that life is normal, and the same applies to clinical practice. So, what can we do?

Elf-actualisation can only be fulfilled after other, more basic needs are fulfilled: physiological needs; safety; love & belonging; and (elf-)esteem (adjusted from Maslow, 1946).

How can we support individuals during the pandemic?

How can we take all these factors into account? Depending on the individual, it may not be best to launch immediately into challenging of thoughts. We may first need to climb down the pyramid and address more basic needs.

Psychological first aid

Here is where the value of Psychological First Aid comes in. In common practice for disaster relief (Everly & Lating, 2017), the role of the mental health professional may be one of having oversight, starting with asking the affected individual what they need, and how the person may be able to help. In many cases, the needs may not be treating mental health symptoms at all, but rather priorities such as housing, health, safety and access to food. From a mental health therapeutic perspective, the approach of Emergency Psychology First Aid is a client-centred one, with emphasis on validation of subjective experiences, thoughts and feelings. Challenging of thoughts at an early stage where the client is overwhelmed would be contra-indicated and would lead to the loss of therapeutic rapport. Social support has been proven to be the key factor in mental recovery in a disaster context (e.g. Cook & Bickman, 1990) and this is also true for more general social embeddedness, and for non-kin support (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993). Building rapport and trust have a central role in the therapeutic attitude and interactions with the client.

So looking at Maslow’s pyramid, cognitive behavioural therapy may come later, after physiological and safety needs are met. Some warnings are in place though. For example, in CBT practice, ‘irrational’ thoughts are identified and addressed, weighing up the evidence for these negative beliefs. Techniques such as thought records or behavioural experiments are used to change any overly negative thoughts into more realistic thinking that is assumed to help decrease low mood and anxiety, and change behaviour accordingly. In some cases, ‘irrational’ thoughts about risk are actually realistic, and assessment should make it clear which is which.

We must also stop to consider whether standard cognitive therapy practice bears a risk of aggravating any rumination patterns. Attention training, or ‘attention bias modification’, a fancy phrase for learning to use distraction to promote good mental health, may sometimes be more suitable. This may be especially true in the current situation. Debriefing after natural disasters is not necessarily beneficial (Van Emmerik et al., 2002) and in cases, focusing on memories of traumatic events (of which there may be plenty at the moment) can increase risk for the development of trauma symptoms (Zetsche et al., 2009).

When we look at the B in CBT, the common techniques of Behavioural Activation and Behavioural Experiments may be limited due to a different way of living during lockdown and social distancing. It’s important for the therapist to be creative here! OXCADAT have a good example of a behavioural experiment in their video on social anxiety, where the therapist involves a few of her colleagues for the experiment.

Looking at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, cognitive behavioural therapy may come later, after physiological and safety needs are met.

Acceptance and commitment therapy

Here is a pragmatic example. A randomised trial offering face-to-face, facilitator-guided, group self-help intervention has been proven useful in relieving distress in Sudanese refugees within a short period of time (Tol et al., 2020). This intervention used structured self-help including components from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). ACT emphasises the role of psycho-education in normalisation and validation of mental health symptoms, fitting well in a Psychological First Aid framework. ACT also aims to increase psychological flexibility, or ‘the ability to contact the present moment more fully and to maintain or change behaviour so that the person behaves in a way that is consistent with their subjectively identified value’ (Tol et al., 2020, p.e257; from: Hayes et al., 2011). What is especially relevant for life during COVID-19, is that in ACT, adapting to (new) situations, without losing sight and losing touch with the key values that someone lives by.

ACT has proven to be helpful for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) by improving emotion regulation (Treanor et al., 2011). This is relevant as a key characteristic of GAD is worrying and catastrophising, something to be expected in these challenging times.

Researchers in Germany have started an online intervention study called ‘CoPE It’ (Bäuerle et al., 2020). As for the Sudanese programme, easy access to the intervention is guaranteed by including ‘boots on the ground’, empowering nurses and social workers to carry out the intervention. ‘CoPE It’ consists of four structured modules including psycho-education, mindfulness and cognitive behavioural skills training. Mindfulness is, like ACT, considered part of the ‘third-wave’ in CBT, and may help individuals emotionally detach from the content of their thoughts. This technique may in the first instance lead individuals to become more aware and focus more on their thoughts and inner experiences. This may be disadvantageous for some individuals who may be at higher risk of developing trauma symptoms. Mindfulness may be protective against the development of trauma from natural disasters, but evidence is slim (Hagen et al., 2016). Mindfulness has been found to be beneficial for distress in military staff before deployment, but no effect was found when practice started after deployment (Atti et al., 2017). I look forward to seeing the results of the ‘CoPE It’ study and understanding if there are any differences between individuals who would benefit most from this intervention in the current context.

Besides timing of specific interventions, individual risk factors deserve special attention in online therapies as these are different in times of lockdown and forced isolation. Ongoing assessment must take account of health conditions, as the situation may change rapidly, and not just for the client, but also for their loved ones. This may have direct implications for the case formulation on which the therapy is based, and for engagement with the therapy.

Conducting online therapy confidentially may be a challenge; parents or partners may be in the room. There is already evidence of increased occurrence of domestic violence, which may have consequences for safeguarding policies.

Confidential online therapy may not be possible for everyone because of their specific household circumstances.

You can’t pour from an empty cup

As none of us are immune, therapists must be extra aware of their own health and mental health conditions. All of us are under prolonged stress, with variations dependent on our individual circumstances, and these increased stress levels can have potential consequences for concentration and mental resilience. In addition, isolation in itself can also have negative psychological impact (Brooks et al., 2020) and has negative effects on concentration (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009).

Online therapy in a time of pandemic is an uncharted territory. As a result, therapists may experience an additional sense of responsibility towards their clients. At the same time, they may not feel they have the same means to address their clients’ needs as they would during practice-as-usual. This may be especially true when the client is personally affected by loss, or in the context of a difficult or risky home situation. Clients may also not be able to take part in remote therapy despite a wish to continue with treatment, increasing a sense of helplessness in the therapist.

Secondary traumatisation can occur when therapists are exposed to the trauma stories of their clients. Shared traumatic situations occur when the therapist experiences the same challenging and potentially traumatic circumstances as their clients, which poses risks for both primary and secondary traumatisation of the therapist (Dekel & Baum, 2010). In social mental health workers, there seems to be more emphasis on understanding stressors and stress outcomes, but less so on moderators of the stress process (Coyle et al., 2005).

Resilience-building techniques, reflective practice and peer-supervision may all support the therapist and ensure effectiveness, but research is needed into their effectiveness and suitability.

In these challenging times, it is not just the client but also the therapist that needs to practice self-compassion and self-care.

Implications for practice

In the current situation, individuals are likely to experience various health and mental health problems (Zhang et al., 2020). Mental health support, including psychological support for healthcare workers, educating COVID-19 health workers, screening patients for mental health symptoms in hospital and monitoring clients with known mental health disorders have all been recommended as part of good clinical practice, in face-to-face as well as online therapy and it is important to address the sense of uncertainty, fear and isolation (Xiang et al., 2020).

As the situation evolves, more and more research is being conducted on the effects of COVID-19 on mental health and funding is being made available.

No-one yet knows what the most suitable interventions in the current climate will prove to be. But we can look at ingredients of the pandemic situation and draw from studies of previous situations with similar challenges and risk factors, and we can embrace guidelines for approaches outside of the regular clinical psychology therapeutic field.

Likely candidates are Emergency First Aid materials, and elements from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. These have proven effective, and they could easily fit within a CBT framework and be incorporated in online clinical practice. Though for the use of ACT, when used as a stand-alone therapy, training would be required, elements from ACT may be adaptable to incorporate into CBT treatment (see the BABCP ACT web page). Psycho-education should have a prominent place, and assessment and formulation should be drawn up carefully keeping all potential contextual factors in mind. Obtaining regular updates and feedback on the effects of certain techniques is recommended, especially techniques that may inadvertently exaggerate any anxiety symptoms (e.g. worrying; catastrophising) in clients that may be considered at risk for developing or sustaining these symptoms.

Extra attention may be paid to meta-cognitions, or beliefs about thoughts and experiences, and specific reactions of the individual client. It may be worthwhile to incorporate elements from meta-cognitive therapy in the treatment when the formulation shows hindering meta-cognitive beliefs (see the references on meta-cognitive therapy below).

Not all symptoms that are to be expected during and after the COVID-19 crisis have been addressed in the OxCADAT guidance. Additional advice would be helpful for mental health problems such as low mood or depressive symptoms; more generalised anxiety in the form of worrying, rumination and catastrophising; health anxiety and obsessive-compulsive thoughts and behaviours to ward off anxiety. In addition, support for grief, though not a recognised disorder, will certainly deserve our attention.

The psychological impact of surviving a pandemic can be huge (Garder & Moallef, 2015). But we also need to keep an eye on those who did not get ill or seem to be coping well in the aftermath.

Emergency First Aid and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy have proven effective and could easily fit within a CBT framework and incorporated in online clinical practice.

Trauma

When it comes to the development of trauma symptoms in the longer-term, it is advised to keep risk factors in mind when screening for, or assessing, mental health symptoms. For example, depression is a proven risk factor for trauma symptoms (Freedman et al., 1999).

Also, pre-trauma symptoms can predict trauma symptoms (Kessler et al., 2014), and it is possible to predict trauma symptoms after disaster (Adams & Boscarino, 2006), both prospectively (Rosselini et al., 2018), and retrospectively (Kesller et al., 2014) from risk profiles, combining risk factors. A study on effects of flooding in China shows that loss, medical trauma, lack of social support, and negative coping style all hinder recovery (Dai et al., 2016). A study conducted after the World Trade Centre attacks shows demographic (younger age, being female, ethnicity) and negative events (number of traumatic events, number of additional negative life events) as risk factors (Adams & Boscarino, 2006). In addition, reduced social support and self-esteem also increased likelihood for the development of PTSD within the first two years after the events (Adams & Boscarino, 2006).

Moral injury in healthcare workers

In the treatment of healthcare workers, attention should be paid in the assessment and formulation to the potential existence of moral injury, when ‘profound psychological distress which results from actions, or the lack of them, which violate one’s moral or ethical code’ (Litz et al., 2009 in: Williamson, Murphy & Greenberg, 2020; Gustavsson et al., 2020). In the COVID-19 situation, the following potential risk factors have been noted for healthcare workers: loss of life, lack of support in general and of responsibility leaders in specific; concurrent exposure to other traumatic events; being unaware or unprepared for the emotional or psychological consequences of decisions (Williamson, Murphy & Greenberg, 2020).

Psychological strain is a particular hazard for health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more in Heather McClelland’s blog on Neil Greenberg’s recent BMJ editorial.

Summary

Even though the current situation with the COVID-19 pandemic is challenging for mental health professionals, there is a huge amount of evidence-based information and resources available on online CBT and Psychological First Aid, and on the effects of natural disasters and SARS on mental health, that can potentially be applied to the current COVID-19 circumstances. Experts from all areas, including OxCADAT, are contributing to new developments for remote delivery of therapy, and online cognitive behavioural therapy.

If we all pull together, we can make a difference: we can advance our field, support our colleagues, and deliver the best possible mental healthcare, both during and after the pandemic.

Online CBT is effective, but you can ask for adjustments in drawing up exercises together with the client – don’t be afraid to improvise!

Table 1: Overview of recent literature on online therapy for common mental health disorders

Almost all of the papers included below are reviews*

| Condition/ population | References |

| Anxiety | Olthuis et al. (2015) |

| Stefanopoulou et al. (2019) | |

| Anxiety in adolescents | Stefanopoulou et al. (2018) |

| Stjerneklara et al. (2018) | |

| Childhood anxiety | Rooksby et al. (2015) |

| Santilhano (2019) | |

| Mixed anxiety and depression | Newby et al. (2014) |

| Anxiety and depression | Andrews et al. (2018) |

| Newby et al. (2017) | |

| Titov et al. (2011) | |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al. (2014) | |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al. (2017) | |

| Anxiety and depression in adolescents | Grist et al. (2019) |

| Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents | O’dea et al. (2015) |

| Richardson et al. (2010) | |

| Stasiak et al. (2015) | |

| Beattie et al. (2009). Qualitative study | |

| Social anxiety | Tulbure (2011) |

| Depression | Andersson et al. (2013) |

| Hedman et al. (2014) | |

| Karyotaki et al. (2018) | |

| Pugh et al. (2014). Case-study. | |

| Renton et al. (2014) | |

| Saddicha et al. (2014) | |

| Sztein et al. (2018) | |

| Stefanopolou et al. (2018) | |

| Wagner (2014) internet versus face-to-face CBT | |

| Zhao et al. (2017) | |

| Depression in adolescents | Martinez et al. (2019) |

| Wozney et al. (2017) Treatment design | |

| Trauma | Kuester et al. (2016) |

| Lewis et al. (2018) | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Aboujaoude (2017) comparing computerised / online / virtual reality platforms |

| Vogel et al. (2012) phone versus video; case-series | |

| Wootton et al. (2015) elf-guided internet CBT | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder for youth | Storch et al. (2011) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | Christensen et al. (2014) |

| Richards et al. (2015) | |

| Psychosis | Baker et al. (2018) |

| Lal et al. (2020) | |

| Online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions | Clarke et al. (2015) |

| Pros and cons of online CBT | Andersson & Cuijpers (2008) |

| Support factors in therapy | Shim et al. (2017) |

| Guidance to improve the therapeutic relationship when working remotely | Helgadottir (2009) |

| A psychodynamic perspective on online psychotherapy for adults | De Bittencourt Machado et al. (2016) |

| Use of different platforms for online therapy | Aboujaoude (2015) describing computerised / internet / mobile / virtual reality versions |

* Resources obtained via systematic search by Liesbeth Tip on 25-03-2020 using EMBASE, with as search terms ‘online AND therapy AND (CBT OR cognitive behavioural therapy) AND review’ Additional relevant literature was identified via colleagues on Twitter, received from Dr Simona di Folco (University of Edinburgh); the ACT article from Tol et al. (2020) and the Face COVID eBook based on ACT were received from Dr David Gillanders (University of Edinburgh). Retrieval of any other article and additional open access resources was conducted by Liesbeth Tip from March 2020 until 29-04-2020 inclusive. All resources are either included in this table and/or described or referred to throughout this blog.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Dr. Simona di Folco (University of Edinburgh) for her invaluable input on Psychological First Aid and inside knowledge of clinical psychology developments in Italy, and contribution of resources on the subject.

Thanks also go to Dr David Gillanders, Prof Liz Gilchrist, Dr Donatella Tamborrini, Prof Matthias Schwannauer and Dr Rachel Happer (all associated with the University of Edinburgh) for their feedback and pointing out some of the links/materials.

Disclaimer

Liesbeth Tip is a registered Clinical psychologist (HCPC), trained Cognitive Behavioural Therapist and accredited CBT scientist (VGCT, The Netherlands). She is a Clinical Fellow and PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, School of Health in Social Science. Her PhD subject is ‘Social anxiety in psychosis’.

She teaches on the Masters of Psychological therapies (https://www.ed.ac.uk/health/subject-areas/clinical-psychology/postgraduate-taught/msc-psychological-therapies). This Master’s programme offers courses on CBT for mental health professionals (not just for psychologists!). The CBT courses have a blended structure and some courses and course elements can be followed online. Adapting CBT practice to remotely delivered CBT is part of the curriculum.

Liesbeth is also involved in the development of the new Centre for Psychological Therapies at the University of Edinburgh, which is linked to the Master’s programme.

Useful links

Note: This list, though extensive, is by no means exhaustive.

Resources for remote delivery of therapy

Minddistrict, information on video sessions and online therapy: https://www.minddistrict.com/video-sessions?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=paid-tweet&utm_campaign=video-calling&utm_content=conversation-image

NHS England guide for remote therapy: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/publication/iapt-guide-for-delivering-treatment-remotely-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

Mentalhealthonline.org.au, which is an organisation that offers online therapy, has published a practical guide on their website for video mental health consultation: https://www.mentalhealthonline.org.au/pages/video-mental-health-consultation

British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP): https://www.babcp.com/Therapists/Remote-Therapy-Provision.aspx

British Psychological Association (BPS); general guidance on therapy delivere during COVID-19, including advice for remote delivery: https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/www.bps.org.uk/files/News/News%20-%20Files/Guidance%20for%20Psychological%20Professionals%20during%20Covid-19.pdf

British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP): https://www.bacp.co.uk/media/2162/bacp-working-online-supplementary-guidance-gpia047.pdf and https://www.bacp.co.uk/news/news-from-bacp/coronavirus/working-online-resources/

Information from professional bodies for COVID-19

British Psychological Society: https://www.bps.org.uk/member-microsites/division-clinical-psychology/resources

British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy: https://www.bacp.co.uk/news/news-from-bacp/coronavirus/faqs-about-coronavirus/

Psychological First Aid

Psychological First Aid guide by National Child Traumatic Stress Network and National Center for PTSD:

https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//pfa_field_operations_guide.pdf

https://www.nctsn.org/treatments-and-practices/psychological-first-aid-and-skills-for-psychological-recovery/about-pfa

Psychological First Aid (PFA) and Skills for Psychological Recovery (SPR) by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network: https://learn.nctsn.org/course/index.php?categoryid=11

Course on psychological first aid to people in an emergency by employing the RAPID model: Reflective listening, Assessment of needs, Prioritization, Intervention, and Disposition, organised by Johns Hopkins University. The course is free and open access, or you can pay to obtain a certificate of participation: https://www.coursera.org/learn/psychological-first-aid

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in a CBT context

For more information on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in a CBT context, information is on the BABCP website: https://www.babcp.com/Membership/SIG/ACT.aspx

Also, the Association of Clinical Psychologists runs seminars on ACT as part of their COVID-19 response: https://acpuk.org.uk/covid_19_response/

Face COVID guide by the British Association of Pediatric Surgeons: https://www.baps.org.uk/professionals/covid-19-information-for-paediatric-surgeons/attachment/face-covid-by-russ-harris-pdf-pdf/ also, google for Face COVID ebook, on website https://www.actmindfully.com.au/wp-content/uploads/ (behind Captcha I’m not a robot security wall)

Face COVID video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmvNCdpHUYM

Meta-cognitive therapy

Meta-cognitive therapy, research from the MCT Institute: https://mct-institute.co.uk/research/

General resilience resources for COVID-19

Samaritans support and resilience information: https://www.samaritans.org/scotland/how-we-can-help/support-and-information/if-youre-having-difficult-time/if-youre-worried-about-your-mental-health-during-coronavirus-outbreak/

Mind support and information: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/coronavirus/coronavirus-and-your-wellbeing/

Centre for Mental Health managing our mental health during COVID-19: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/coronavirus-update

NHS Lothian https://services.nhslothian.scot/LanfineService/COVID19/mentalhealth/Pages/default.aspx

Trauma

There are lots of resources and links on the UCL COVID Trauma Response Workgroup: https://www.traumagroup.org/ Including a document on Psychological First Aid: https://232fe0d6-f8f4-43eb-bc5d-6aa50ee47dc5.filesusr.com/ugd/6b474f_a6f6d0a5cba34ce98629bfd03a2a9c8b.pdf

Guidelines for bereavement

Bereavement charter for children and adults in Scotland: https://scottishcare.org/bereavement/

Children and young people

NHS Lothian https://services.nhslothian.scot/camhs/Resources/Pages/ResourcePacks.aspx

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde https://www.nhsggc.org.uk/kids/supporting-children-and-young-people-during-covid-19/

Anna Freud Centre https://www.annafreud.org/what-we-do/anna-freud-learning-network/coronavirus/

Useful links are on the website for the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive & Critical Care Societies

Resources for parents and carers to help support children & young people with their worries and anxiety around COVID-19, from Emerging Minds: https://emergingminds.org.uk/advice-for-parents-carers-supporting-children-young-people-with-worries-about-covid-19/

Unicef: https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/how-talk-your-child-about-coronavirus-covid-19

Risk & Safeguarding, domestic abuse:

Guidance for working with children at-risk by collaborators (PDF) from King’s College London, UKRI Violence Abuse and Mental Health Network, Survivors’ Voices

Reference: Chevous. J, Oram. S, Perôt. C (2020), Supporting ‘off-radar’ children & young people at risk of violence and abuse in their household.Survivors’ Voices, UKRI Violence Abuse and Mental Health Network, McPin Foundation. London.

Scottish Government https://www.gov.scot/news/support-for-victims-of-domestic-violence-during-covid-19-outbreak/

Safelives https://safelives.org.uk/news-views/domestic-abuse-and-covid-19

Scottish Women’s Rights Centre https://www.scottishwomensrightscentre.org.uk/news/covid-19coronavirus-info/domestic-abuse-during-covid-19coronavirus-what-can-i-do/

Support for key workers

Pandemic Influenza Plan – Psychosocial Services Preparedness (PDF) by the Missouri Department of Health (https://health.mo.gov/)

Managing mental health challenges faced by health careworkers during covid-19 pandemic (PDF). Document by Neil Greenberg and colleagues (2020) BMJ 2020;368:m1211 DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m1211

Samaritans have a mental health hotline for NHS staff: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-52202570

UCL video of guidelines for hospital staff: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WFWvkjJ755Y&feature=youtu.be

The Cost of Living site ‘is for all people interested in the politics, economics and sociology of health and health care’; it has guidance based on research with A & E doctors: https://www.cost-ofliving.net/we-need-rest-not-reflection-psychological-support-for-the-medical-frontline/

Academic journals / institutions that cover remote delivery for mental health

The Academic Journal Internet Interventions offers open access articles on the application of information technology in mental and behavioural health: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/internet-interventions

The Journal of Medical Internet Research is a peer-reviewed journal for digital medicine and health and health care in the internet age: https://www.jmir.org/

Frontiers in Psychiatry has a research topic on ‘Digital Interventions in Mental Health: Current Status and Future Directions’, which includes an eBook: https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/9243/digital-interventions-in-mental-health-current-status-and-future-directions#articles

Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, provides peer reviewed coverage of developments in telemedicine and e-health: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/jtt

In 1997, the International Society for Mental Health Online (ISMHO) was formed, ‘to promote the understanding, use and development of online communication, information and technology for the international mental health community’ : http://ismho.org/ismho/about-ismho/

Research on mental health and COVID-19

How Psychology Researchers Are Responding To The COVID-19 Pandemic. BPS website: https://digest.bps.org.uk/2020/03/26/how-psychology-researchers-are-responding-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/amp/

University of Oxford, Co-Space study: COVID-19: supporting parents, adolescents and children during epidemics. https://oxfordxpsy.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3VO130LTKOcloMd

The Lancet published an article, pointing out key ethical questions for research during COVID-19: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30150-4

Pre-print by Inchausti et al. (2020) on psychological interventions and the COVID-19 pandemic: https://psyarxiv.com/8svfa Inchausti, F., MacBeth, A., Hasson-Ohayon, I., & Dimaggio, G. (2020, April 2). Psychological interventions and the Covid-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8svfa

Pre-print by Van Bavel et al. (2020) on PsyArXiv on social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 response: Van Bavel, Jay J., Katherine Baicker, Paulo Boggio, Valerio Capraro, Aleksandra Cichocka, Molly Crockett, Mina Cikara, et al. 2020. “Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response.” PsyArXiv. March 24. doi:10.31234/osf.io/y38m9.

Pre-print by IJzerman et al. (2020) on PsyArXiv on the readiness of psychological science for crises: https://psyarxiv.com/whds4 IJzerman, H., Lewis, N. A., Jr., Weinstein, N., DeBruine, L. M., Ritchie, S. J., Vazire, S., … Przybylski, A. K. (2020, April 27). Psychological Science is Not Yet a Crisis-Ready Discipline. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/whds4

Generation Scotland, a research group at the University of Edinburgh, is conducting research: https://www.ed.ac.uk/covid-19-response/latest-news/survey-of-covid-19-s-impact-on-our-everyday-lives

Courses

University of Glasgow, MSc Digital Health Interventions: https://www.gla.ac.uk/postgraduate/taught/digitalhealthinterventions/

Links

Primary paper

OxCADAT (2020) OxCADAT COVID-19 resources. Oxford Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma website, last accessed 1 May 2020.

Remote Delivery Guidance:

- Cognitive Therapy for PTSD – Remote delivery guidance for memory work (PDF)

- Cognitive Therapy for Social Anxiety – Remote delivery guidance (PDF)

- Cognitive Therapy for Panic Disorder – Remote delivery guidance (PDF)

Other references

Aboujaoude, A., Salame, W. & Naim, L. (2015). Telemental Health: a status update. World Psychiatry, 14, 223-230.

Aboujaoude, E. (2017). Three decades of telemedicine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A reviewacross platforms. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 14, 65-70.

Adams, R. E. & Boscarino, J. A. (2006). Predictors of PTSD and delayed PTSD after disaster. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 7, 485-493. DOI:10.1097/01.nmd.0000228503.95503.e9.

Andersson, G. & Cuijpers, P. (2008). The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193, 270-271. oi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054080

Andersson, G., Hesser, H., Veilord, A., Svedling, L., Andersson, F., Sleman, O., Mauritzson, L., Sarkohi, A., Claesson, E., Zetterqvist, V., Lamminen, M., Eriksson, Th. & Carlbring, P. (2013). Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial with 3-year follow-up of internet-delivered versus face-to-face group cognitive behavioural therapy for depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151, 986-994.

Andrews, G., Basu, A., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., English, C. L., Newby, J. M. (2018). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 7-78.

Armitage & Nellum (2020). COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. The Lancet Public Health. DOI: htps://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

Atti, S., Alfalasi, R., Mahon, S. E. & Ciottone, G. (2017) Mindfulness in Disaster Response. Prehospital and disaster medicine, 32, S1, 181. DOI: 10.1017/S1049023X17004812

Baker, A. L., Turner, A., Beck, A. Berry, K., Haddock, G., Kelly, P. J. & Bucci, S. (2018). Telephone-delivered psychosocial interventions targeting key health priorities in adults with a psychotic disorder: systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 48, 16, 2637-2657.

Bäuerle, A., Skoda, E., Dörrie, N., Böttcher, J. & Teufel, M. (2020) Psychological support in times of COVID-19: the Essen community-based CoPE concept. Journal of Public Health, fdaa053, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa053

Beattie, A., Shaw, A., Kaur, S. & Kessler, D. (2009). Primary-care patients. Expectations and experiences of online cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a qualitative study. Health Expectations, 12, 45–59

De Bitencourt Machado, D., Braga Laskoski P., Trelles Severo C., Margareth Bassols A., Sfoggia A., Kowacs C., et al (2016). A Psychodynamic Perspective on a Systematic Review of Online Psychotherapy for Adults. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 32, 79-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12204

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wesseley, S., Greenberg, N. & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Cacioppo, J. T. & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13, 10, 447-454. DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005

Christensen, H., MacKinnon, A. J., Batterham, Ph. J., O’dea, B., Guastella, A. J., Griffiths, K. M. (2014). The effectiveness of an online e-health application compared to attention placebo or Sertraline in the treatment of Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Internet interventons, 1, 169-174.

Clarke, A. M., Kuosmanen, T. & Barry, M. M. (2015). A Systematic Review of Online Youth Mental Health Promotionand Prevention Interventions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1, 1-24. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-014-0165-0

Cook, J. D. & Bickman, L. (1990). Social support and psychological symptomatology following a natural disaster. Journal of traumatic stress, 3, 4, 541-556.

Coyle, D., Edwards, D., Hannigan, B., Fothergill, A. & Burnard, Ph. (2005). A systematic review of stress among mental health social workers. International Social Work, 48, 2, 201–211. DOI: 10.1177/0020872805050492

Dai, W., Wang, J., Kaminga, A. C., Chen, L., Tan, H., Lai, Z., Deng, J. & Liu, A. (2016). Predictors of reovery from post-traumatic stres disorder after the dongting lake flood in China: a 13-14 year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 382. DOI 10.1186/s12888-016-1097-x

Dekel, R. & Baum, N. (2010). Intervention in a shared traumatic reality: a new challenge for social workers. British Journal of Social Work, 40, 6, 1927-1944. DOI: 10.1093/bjsw/bcp137

Van Emmerik, A. A. P., Kamphuis, J. H., Hulsbosch, A. M. & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2002). Single session debriefing after psychological trauma: a meta-analysis. The Lancet, 360, 9335, 7766-771. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09897-5

Everly, G. & Lating, J. M. (2017). The Johns Hopkins Guide to Psychological First Aid. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Freedman, S. A., Brandes, D., Peri, T. & Shalev, A. Y. (1999). Predictors of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: A prospective study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 4, 353-359.

Gardner, P. J. & Moallef, P. (2015). Psychological impact on SARS survivors: critical review of the English language literature. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 56, 1, 123–135.

Garrido, S., Millington, C., Cheers, D., Boydell, K., Scubert, E. & Meade, T. (2019). Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression andAnxiety in Young People. Frontiers in Psychiatry. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00759

Grist, R., Croker, A., Denne, M. & Stallard, P. (2019). Technology Delivered Interventions for Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22, 147–171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0271-8Technology Delivered I

Gustavsson, M., Arnberg, F., Juth, N., & Von Schreeb, J. (2020). Moral Distress among Disaster Responders: What is it? Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 35, 2, 212-219. doi:10.1017/S1049023X20000096

Hadjistavropoulosa, H. D., Pugham N. E., Nugent, M. M., Hesser, H., Andersson, G., Ivavnovd, M., Butz, C. G.Butzd, Marchildone, G., Asmundsona, G. J. G., Klein, B. & Austin, D. W. (2014). Therapist-assisted Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for depression and anxiety:Translating evidence into clinical practice. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 884–893

Hadjistavropoulosa, H. D., Schneidera, L. H., Edmondsa, M., Karinb, E., Nugenta, M. N., Dirksea, D., Dearb, B. F. & Titovc, N. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy comparing standard weekly versus optional weekly therapist support. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 52, 15-24.

Hagen, C., Lien, L., Hauff, E. & Heir, T. (2016). Is mindfulness protective against PTSD? A neurocognitive study of 25 tsunami disaster survivors. Journal of negative Results in Biomedicine, 15, 13. DOI: 10.1186/s12952-016-0056-x

Hayes, S. C., Villatte, M., Levin, M., Hildebrandt, M.. (2011). Open, aware, and active: contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 141–68.

Hedman, E., Ljotsson, B., Kaldo V., Hesser, H., El Alaoui, S., Kraepelien, M., Andersson, E., Ruck, C., Svanborg, C., Andersson, G. & Lindefors, N. (2014). Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in routine psychiatric care. Journal of Affective Disorders, 155, 49-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.023

Helgadottir, F.D., Menzies, R.G., Onslow, M., Packman, A. & O’Brian, S. (2009). Online CBT I: Bridging the gap between Eliza and modern online CBT treatment packages. Behaviour Change, 26, 245-253. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.26.4.245

Kaniasty, K. & Norris, F. H. (2017). A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 3, 395-408.

Karyotaki, E., Ebert, D.D., Donkin, L., Riper, H., Twisk, J., Burger, S., Rozental, A., Lange, A., Williams, A.D., Zarski, A.C., Geraedts, A., Van Straten, A., Kleiboer, A., Meyer, B., Unlu Ince, B.B., Buntrock, C., Lehr, D., Snoek, F.J., Andrews, G., Andersson, G., Choi, I., Ruwaard, J., Klein, J.P., Newby, J.M., Schroder, J., Laferton, J.A.C., Van Bastelaar, K., Imamura, K., Vernmark, K., Boss, L., Sheeber, L.B., Kivi, M., Berking, M., Titov, N., Carlbring, P., Johansson, R., Kenter, R., Perini, S., Moritz, S., Nobis, S., Berger, T., Kaldo, V., Forsell, Y., Lindefors, N., Kraepelien, M., Bjorkelund, C., Kawakami, N. & Cuijpers, P. (2018). Do guided internet-based interventions result in clinically relevant changes for patients with depression? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.007

Kessler, R.C., Rose, S., Koenen, K.C., Karam, E.G., Stang, P.E., Stein, D.J., Heeringa, S.G., Hill, E.D., Liberzon, I., McLaughlin, K.A., McLean, S.A., Pennell, B.E., Petukhova, M., Rosellini, A.J., Ruscio, A.M., Shahly, V., Shalev, A.Y., Silove, D., Zaslavsky, A.M., Angermeyer,M.C., Bromet, E.J., De Almeida, J.M.C., De Girolamo, G., De Jonge, P., Demyttenaere, K., Florescu, S.E., Gureje, O., Haro, J.M., Hinkov, H., Kawakami, N., Kovess-Masfety, V., Lee S., Medina-Mora, M.E., Murphy, S.D., Navarro-Mateu, F., Piazza, M., Posada-Villa, J., Scott, K., Torres, Y. & Viana, M.C. (2014). How well can post-traumatic stress disorder be predicted from pre-trauma risk factors? An exploratory study in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. World Psychiatry, 13, 265–274.

Kuester, A., Niemeyer, H. & Knaevelsrud, C. (2016). Internet-based interventions for posttraumatic stress: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology review, 43, 1-16.

Lal, S., Abdel-Baki, A., Sujanani, S., Bourbeau, F., Sahed, I. & Whitehead, J. (2020). Perspectives of Young Adults on Receiving Telepsychiatry Services in an Urban Early Intervention Program for First-Episode Psychosis: A Cross-Sectional, Descriptive Survey Study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00117

Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Bethell, A., Robertson, L. & Bisson, J. I. (2018). Internet-based cognitive and behavioural therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. Art. No.: CD011710. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011710.pub2.

Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E. et al. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 695–706.

Martinez, A., Rojas, G., Martinez, P., Gaete, J., Zitko, P., Vöhringer, P. A. & Araya, R. (2019). Computer-Assisted Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy to Treat Adolescents With Depression in Primary Health Care Centers in Santiago, Chile: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 552. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00552

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motication. Psychological Review, 50, 4, 370-396.

Newby, J. M., Mewton, L. & Andrews, G. (2017). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 25–34.

Newby, J. M., Mewton, L., Williams, A. D. & Andrews, G. (2014). Effectiveness of transdiagnostic internet cognitive behavioural treatment for mixed anxiety and depression in primary care. Journal of affective disorders, 165, 45-52.

O’dea, B., Calear, A. L. & Perry, Y. (2015). Is e-health the answer to gaps in adolescentmental health service provision? Current opinion in Psychiatry, 28, 4, 336-42. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000170.

Olthuis, J. V., Watt, M. C., Bailey, K., Hayden, J. A. & Stewart, S.H. (2015). Therapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD011565. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011565.

Pugh, N. E., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Klein, B. & Austin, D..(2014). A Case Study Illustrating Therapist-Assisted Internet Cognitive BehaviorTherapy for Depression. Cognitive and Behavioural Practice, 21, 64-77.

Richards, D., Richardson, Th., Timulak, L. & McElvaney, J. (2015). The efficacy of internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxietydisorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Internet Interventions, 2, 272-282.

Renton, T., Tang, H., Ennis, N., Cusimano, M. D., Bhalerao, S., Schweizer, T. A., Topolovec-Vranic, J. (2014). Web-based intervention programs for depression: a scoping review and evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.3147

Richardson, Th., Stallard, P. & Velleman, S. (2010). Computerised Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for the Preventionand Treatment of Depression and Anxiety in Childrenand Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 275–290. DOI 10.1007/s10567-010-0069-9

Rosselini, A. J., Dussaillant, F., Zubizaretta, J. R., Kessler, R. C. & Rose, S. (2018). Predicting Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Following a Natural Disaster. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 15-22. DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.010.

Rooksby, M., Elouafkaoui, P., Humphris, G., Clarkson, J. & Freeman, R. (2015). Internet-assisted delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for childhood anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 29, 83-92.

Saddicha, S., Al-Desouki, M., Lamia, A., Linden, I. A. & Krausz, M. (2014). Online interventions for depression and anxiety – a systematic review. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 2, 1, 841-881, DOI:10.1080/21642850.2014.945934

Santilhano, M. (2019). Online intervention to reduce pediatric anxiety: An evidence‐based review. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 32, 197-209.

Shim, M., Mahaffey, B., Bleidistel, M & Gonzalez, A. (2017). A scoping review of human-support factors in the context of Internet-basedpsychological interventions (IPIs) for depression and anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 129-140.

Stasiak, K., Fleming, T., Lucassen, M. F. G., Shepherd, M. J., Whittaker, R. & Merry, S. N. (2016). Computer-Based and Online Therapy for Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26, 3, 235–245.

Stefanopoulou, E., Lewis, D., Taylor, M., Broscombe, J., Ahmad, J. & Larkin, J. (2018). Are Digitally Delivered Psychological Interventions for Depression the Way Forward? A Review. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89, 779-794. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9576-5

Stefanopoulou, E., Lewis, D., Taylor, M., Broscombe, J. & Larkin, J. (2019). Digitally delivered psychological interventions for anxiety disorders: a comprehensive review. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90, 197-215. DOI: htttps://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-018-9620-5

Stjerneklara, S., Hougaarda, E., Nielsenb, A., Gaardsviga, M. M. & Thastuma, M. (2018). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with anxiety disorders: A feasibility study. Internet Interventions, 11, 30-40.

Storch, E. A., Caporino, N. E., Morgan, J. R., Lewin, A. B., Rojas, A., Brauer, L., Larson, M. J. & Murphy, T. K. (2011). Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy foryouth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 189, 407-412.

Sztein, D. M., Koransky, C. E., Fegan, L. & Himelhoch, S. (2018). Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapydelivered over the Internet for depressivesymptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24, 8, 527–539.

Tol, W. A., Leku, M. R., Lakin, D. P., Carswell, K., Augustinavicius, J., Adaku, A., Au, T. M., Brown, F. L., Bryant, R. A., Garcia-Moreno, C., Musci, R. J., Ventevogel, P., White, R. G., Van Ommeren, M. (2020). Guided self-help to reduce psychological distress in South Sudanese female refugees in Uganda: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health, 8, e254-263.

Treanor, M., Erisman, S. M., Salters-Pednault, K., Roemer, L. & Orsillo, S. (2011). An acceptance-based behavioral therapy for GAD: effects on outcomes from three theoretical models. Depression and Anxiety, 2, 127–136. DOI:10.1002/da.20766.

Titov, N., Dear, B. F., Schwencke, G., Andrews, G., Johnston, L., Graske, M. G. & McEvoy, P. (2011). Transdiagnostic internet treatment for anxiety and depression: A randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 441-452.

Tulbure, B. T. (2011). The efficacy of Internet-supported intervention for social anxiety disorder: A brief meta-analytic review. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 552 – 557.

Vogel, P. A., Launes, G., Moen, E. M., Solem, S., Hansen, B., Tellefsen Haland, A., Himle, J. A. (2012). Video conference-and cell phone-based cognitive-behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder:A case series. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 158-164.

Wagner, B., Horn, A. B. & Maercker, A. (2014). Internet-based versus face-to-face cognitive-behavioral intervention for depression: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152-154, 113-121.

Williamson, Murphy & Greenberg (2020). COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. Occupational Medicine. DOI: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa052

Wootton, B. M., Dear, B. F., Johnston, L., Terides, M. D. & Titov, N. (2015). Self-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) for obsessive–compulsive disorder: 12 month follow-up. Internet Interventions, 2, 243-247.

Wozney, L., Huhuet, A., Bennett, K., Radomski, A. D., Dyson, M., McGrath, P. J. & Newton, A. S. (2017). How do eHealth Programs for Adolescents With Depression Work?A Realist Review of Persuasive System Design Components inInternet-Based Psychological Therapies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, 8, e266. DOI: http://www.jmir.org/2017/8/e266/

Wu, D. Yu, L., Cottrell, R., Peng, S., Guo, W. & Jiang, S. (2020). The Impacts of Uncertainty Stress on Mental Disorders of Chinese College Students: Evidence From a Nationwide Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 243. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00243

Xiang, Y., Yuang, Y., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Cheung, T. & Ng C. H. (2020). The Lancet Psychiatry, 7, 228-229. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8

Zetsche, U., Ehring, Th. & Ehlers, A. (2009). The effects of rumination on mood and intrusive memories after exposure to traumatic material: an experimental study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40, 499-514.

Zhang, S., X., Wang, Y., Rauch, A. & Wei, F. (2020). Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112958. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958

Zhao, D., Lustria, M. L. A. & Hendrickse, J. (2017). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Patient education and counselling, 100, 1049-1072.

Photo credits

- Photo by Zachary Nelson on Unsplash

This is an excellent review. I think it is helpful for a range of mental health professionals, even those with a different training to CBT.

interesting positive reviews…

(online CBT with a human via tx)

https://uk.trustpilot.com/review/iesohealth.com?utm_medium=trustbox&utm_source=MicroCombo

p.s. I have no connection