One in eight children and young people in the United Kingdom experience at least one mental health problem (NHS Digital, 2018). Mental health support for young people can be difficult to receive, particularly during the transition between child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and adult services (Hill et al., 2019).

Timely access to mental health support options is important because experiencing a mental health problem such as depression in childhood and adolescence is linked to experiencing mental health problems as an adult (read Katie Finning’s previous elf blog), as well as poorer social outcomes (read Maria Loades’ previous elf blog). Therefore, identifying worsening mental health in young people in real-time may help to prevent future difficulties in later life.

Technology use is commonplace in society; particularly in young people. In the UK, 96% of young people aged 16-24 report owning a smartphone, whilst 94% report having at least one social media account (Statista, 2018). Wearable technology rates of ownership are comparatively lower (17%) but use by young people is increasing in the UK (Ofcom, 2019).

Such high rates of technology ownership and use mean that it might be possible to use these approaches to identify and prevent deteriorating mental health in young people. A large proportion of published research studies have identified that many adults (ages 18-70) who experience mental health problems find the idea of using technology to manage their mental health acceptable (e.g. Stawarz et al., 2019; Terp et al., 2018). However, little is known specifically about young people’s views towards using technology to help identify and monitor deteriorations in their mental health.

Therefore, the aim of a recent qualitative study (Dewa et al., 2019) was to explore the views of young adults towards the acceptability and feasibility of using wearables, social media and other technologies to detect worsening mental health.

One in eight children and young people in the UK experience at least one mental health problem and 96% of young people aged 16-24 report owning a smartphone.

Methods

All elements of the research design and analysis were co-created with young people with lived experience of mental health problems who were recruited via the research charity The McPin Foundation (www.mcpin.org) and Twitter. Following an internal selection process, seven young people were recruited to work on the study and assigned their requested role (e.g. project management, data collection and analysis or dissemination). It was agreed that the young people would be referred to as co-researchers during the study.

Participants were identified through an NHS Trust database of service users under the care of a community mental health team and approached by a consultant psychiatrist (also a co-author on the paper). The psychiatrist asked them if they would be interested in hearing more about the project from the researcher who then contacted them via telephone with further information.

The authors conducted 16 face-to-face semi-structured interviews with young adults who had received a diagnosis of a mental health problem. The mean age of participants was 22 (range 19-24) and participants were predominantly female (81%). Interviews were guided by a topic guide, which was co-created with the co-researchers.

Interview questions focussed on:

- Introductory questions (including reassurance they were in a safe space)

- Use of and attitudes toward different types of technologies (e.g. social media, wearables, smartphone apps)

- Experience of mental health worsening (e.g. what happened, how was it first identified)

- The acceptability of using technology to support mental health

- The feasibility of using technology to identify mental health deterioration.

The interviews were initially delivered by the lead author, who was shadowed on separate occasions by two co-researchers who were also given the opportunity to ask questions. The co-researchers conducted two interviews each and received debriefing and feedback by the lead author. The lead author completed the remaining interviews.

The data were analysed thematically and the authors promoted triangulation through the involvement of researchers with experience of mental health research and co-researchers with lived experience of mental health problems. The two researchers and co-researchers coded three transcripts each and co-created an initial framework to code the remaining transcripts. New codes and subsequent themes were discussed over three sequential face-to-face meetings. Analysis was completed in a 2-hour virtual meeting to finalise themes and create a thematic map.

Results

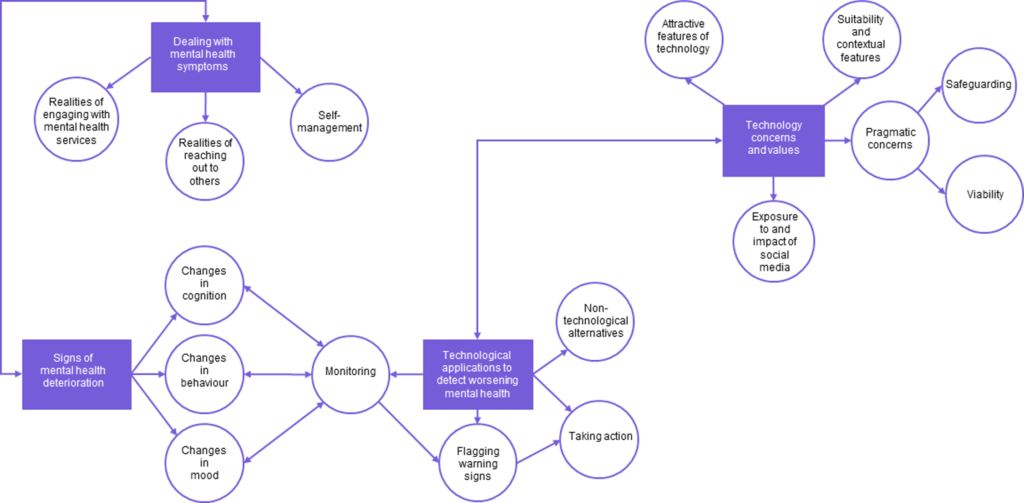

The analysis revealed a total of four main themes, which are presented in a thematic map:

Figure 1 page 5. Researchers identified 4 main themes relating to young peoples’ views towards using technology to detect worsening mental health. View full size

1. Dealing with mental health symptoms

1a. Reality of engaging with mental health services

Half the participants reported some difficulties in engaging with mental health services and several reported negative experiences of services at times of crisis. Access difficulties included lengthy waiting lists, perceptions that it was useless asking for help because none would be provided, and issues with capacity when experiencing symptoms.

In contrast, a few participants reported receiving helpful support in a timely manner which had subsequently improved their mental health.

1b. Realities of reaching out to others

There were mixed experiences of seeking support from others such as friends and family. Some participants did not reach out because of stigma or the worry that others would not understand. However, once they had reached out, participants reported receiving helpful support, particularly from friends.

1c. Self-management

Participants gave numerous examples of how they attempted to self-manage their mental health including:

- Being proactive and self-aware of their triggers;

- Using avoiding strategies and hiding symptoms;

- Using unsafe coping strategies (e.g. drinking excessively, taking drugs or self-harming)

2. Signs of mental health deterioration

All participants identified that changes in their mood, behaviour or cognition were a sign that their mental health may be worsening. Reported changes in mood included irritability, low mood, hopeless and lack of motivation, whilst reported behaviours included outbursts, excessive behaviour, social isolation and changes to routine, eating and sleep. Similarly, increases in impulsivity, hyperactivity and hearing voices were also highlighted as indicators of mental health deterioration.

3. Technology concerns and values

3a. Attractive features of technology

Participants valued the anonymity and accessibility of technology, where they felt comfortable being able to speak openly without judgment at a time and place convenient for them.

3b. Suitability and contextual factors

Mixed views were presented about whether mental health deterioration should be captured automatically (e.g. monitoring sleep and activity through wearables, smartphone apps and social media activities) or through self-report (e.g. via questions on a smartphone app). In the case of self-report, concerns were raised as to whether they would have the motivation to complete entries as they may not be in the right mindset. Several participants were also worried that social media posts may not be truly be reflective of an individual’s mental state, with two participants noting they had previously posted dark images on social media, but had not been unwell or needing help.

3c. Pragmatic concerns

Participants were concerned that there may be issues with safeguarding and validity when using technology to identify mental health deterioration. Specifically, false negatives or positives might result in help being offered when it is not needed or help not being provided when an individual’s mental health was deteriorating. Reliance on WiFi connectivity, expense of technology, loss of devices and insufficient battery were listed as issues that could affect someone getting help when needed.

3d. Exposure to and impact of social media

The majority of participants discussed being exposed to negative content on social media such as pro-anorexia content, self-harm pictures, cyberbullying, instructions on how to kill yourself and romanticising suicide.

4. Technological applications to detect worsening mental health

The final theme integrates the three previous themes through using technology to deal with mental health symptoms, identify signs of deterioration, and technological concerns and values.

Most participants agreed that monitoring their mental health using technologies such as apps, wearables and social media could be possible for spotting signs of deterioration earlier. Additionally, participants believed that whilst monitoring and flagging warning signs was needed, acting on these was vital. Suggested actions included displaying helplines, calling an ambulance or other emergency services, having immediate online access to a designated psychiatrist or psychologist or going to hospital.

Mixed views were presented about whether mental health deterioration should be captured automatically (e.g. monitoring sleep and activity through wearables, smartphone apps and social media activities) or through self-report (e.g. via questions on a smartphone app).

Conclusions

There are several key messages that can be taken from this paper when considering the acceptability of using technology to detect worsening mental health in young people.

- The young people interviewed discussed some difficulties in accessing services when help and support were required. Technology could be leveraged to help service access through identifying early individuals whose mental health is deteriorating.

- Young people were able to identify warning signs that indicated potential mental health deterioration, which included changes in mood, behaviour and cognition. Technologies could be used to monitor the signs noted by young people so that intervention options can be delivered as quickly as possible to prevent further deterioration.

- Whilst automatic activity and sleep tracking were viewed as potential indicators of mental health deterioration, some young people highlighted that social media content may not be reflective of their current feelings and behaviours.

- Young people were worried about the potential for false negatives and false positives, whereby individuals were incorrectly contacted or not contacted based on information obtained using technology. Additionally, concerns were raised about the accessibility of technology or some individuals as well as practical concerns such as WiFi connectivity and battery life.

It was felt that social media might not be reflective of current feelings and behaviours.

Strengths and limitations

The authors are to be commended for the involvement of young people with lived experience of mental health problems throughout the lifecycle of the study. Not only were young people involved in the co-creation of study materials, they also actively participated in the data collection, analysis and dissemination stages. Such a collaborative approach to co-production in qualitative research is rare and unique despite the potential for improved validity of research findings.

More information could have been provided by the authors with regards to the selection of individuals as co-researchers to the project. Specifically, it is unclear how many young people applied for the roles, whether individuals were interviewed for roles, how applicants were informed of the decision and whether feedback was provided to unsuccessful applicants. Additionally, the GRIPP2 checklist (Staniszewska et al., 2017) was not completed, which is a reporting checklist designed to improve the quality, transparency and consistency of patient and public involvement. Given the novel approach to co-production in this study, such information would be helpful for other researchers seeking to collaborate with individuals with lived experience in qualitative research studies.

Data rigour was enhanced through the triangulation of data, which was achieved by the involvement of two researchers and two co-researchers in coding and analysis. The authors note that recorded reflexivity was also a strength of the study which contributed to enhancing rigour. However, more information could have been provided about the reflexive process. For example, it would have been interesting to see excerpts of reflexive notes to understand how the authors were reflexive in interviews, coding and analysis. Additionally, member checking (where participants are recontacted with their transcript or a summary of research findings for feedback) was not carried out, which may have affected the accuracy of the findings.

The authors noted that potential participants were first approached by a consultant psychiatrist who was a co-author on the paper. However, it was unclear whether the service users had been under the caseload of this psychiatrist. It could be considered coercive for individuals to be approached by their treating clinician if they are a member of the research team. Therefore, the authors could have clarified whether this was the case and if so, what steps were taken to avoid coercion.

A clear strength of this project was meaningful collaboration with young people with lived experience of mental health problems throughout the lifecycle of the project.

Implications for practice

Although the findings are from a small subset of participants, so will not be representative of young peoples’ views more generally, some tentative implications for practice include:

- Young people generally find the potential for technology to detect worsening mental health as acceptable and feasible. Therefore, it is important that researchers explore how technology can be leveraged to support young people in this way

- Whilst young people could see the feasibility of using mobile apps and wearables for detection, they were concerned that social media activities may not be a true reflection of their feelings and behaviours. There is an increasing amount of research intending to use social media to detect deteriorations in adult mental health. These findings call into question the potential validity of using such approaches within clinical practice

- Young people were concerned that they might not be motivated to complete self-reports in mobile apps at times of deterioration or distress. Steps should be taken to explore how engagement can be promoted during these periods.

In this small study, young people generally found the potential for technology to detect worsening mental health as acceptable and feasible.

Statement of interests

Natalie Berry works as a research associate on a randomised controlled trial investigating the efficacy of a smartphone app (Actissist) for early psychosis.

Links

Primary paper

Dewa LH, Lavelle M, Pickles K, Kalorkoti C, Jaques J, Pappa S, et al. (2019). Young adults’ perceptions of using wearables, social media and other technologies to detect worsening mental health: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 14(9):e0222655.

Other references

Finning, K. What’s the relationship between adolescent depression and adult depression? The Mental Elf, 28th March, 2019.

Hill A, Wilde S, Tickle A. (2019). Transition from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) to adult mental health services (AMHS): a meta-synthesis of parental and professional perspectives. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2019 24(4) 295-306.

Loades, M. Teenage depression linked to poor psychological and social outcomes in later life. The Mental Elf, 20th Feb, 2019.

NHS Digital. (2018). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017.

Ofcom. (2019). Adults media use and attitudes report.

Statista. (2018). Smartphone usage in the UK – by age.

Statista. (2018). Social network profile creation in the UK by age.

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, Seers K. Mockford C, Goodlad S, Altman DG, Moher D. Barber R. Denegri E, Entwistle A, Littlejohns P, Morris C, Suleman R, Thomas V, Tysall C. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ. 357.

Stawarz K, Priest C, Coyle D. (2019). Use of smartphone apps, social media, and web-based resources to support mental health and well-being: online survey. JMIR Mental Health 6(7) e12546.

Terp M, Jørgensen R, Schantz Laursen B, Mainz J, Bjørnes J. (2019). A smartphone app to foster power in the everyday management of living with schizophrenia: Qualitative analysis of young adults’ perspectives. JMIR Mental Health 2018 5(4) e10157.

Photo credits

- Photo by Elena Koycheva on Unsplash

- Photo by Paul Hanaoka on Unsplash

- Photo by Chris Liverani on Unsplash

- Photo by Prateek Katyal on Unsplash

- Photo by Dylan Gillis on Unsplash

- Photo by Simon Maage on Unsplash