I have been a psychiatrist for 60 years. I have seen many changes in clinical practice, but I have to admit that the present situation is without precedent. The flow of people suffering from mental illness is likely to be accentuated by COVID-19. There will be an increased need for treatments such as psychotherapy. However, the need for social distancing makes face-to-face treatments more difficult to deliver.

In this blog, I summarise a recent article examining online psychotherapy interventions. I also describe a long-neglected school of psychotherapy which sprang from the darkest event in my lifetime, and which has valuable lessons for our approach to psychotherapy in a pandemic.

Online psychotherapy has a number of advantages, including accessibility and cost saving.

Methods

McDonald et al presented a narrative review of the evidence for online psychotherapy and described its use in health services around the world.

Results

Online therapy presents several possible advantages compared to face-to-face treatments. Chief of these is accessibility. Treatment can be offered to people who cannot physically visit therapists, full-time employees, and to those in low- and middle-income countries. A further advantage is the potential to lower the cost of treatment, bringing it within reach of lower income people without access to free healthcare, or those who do not be the criteria of healthcare services.

Early online psychotherapy programmes were driven by geographical barriers to treatment. For example, Australia developed Mood GYM and Blue pages, New Zealand developed SPARX in response to poor mental health in a dispersed population of young people.

In the UK, it is recognised that expanding digital technology could control the increasing costs of health care. Government publications such as The NHS Longterm Plan suggests a seamless integrated care across the NHS and associated services.

Research into online treatments have focussed on two key outcomes:

- the improvement of mental wellbeing or symptoms

- the extent of user engagement

(See supplementary Table 1 (Word doc) from McDonald et al)

The evidence base chiefly represents cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) programmes. Packages for anxiety showed weak effects of uncertain significance (observed effect sizes 0.07 to 0.42), however mindfulness programmes, designed to treat people with bipolar disorder, have shown a distinct improvement (effect size of 0.52). Still, such treatment programmes report significant attrition rates.

There is evidence for online psychotherapy, particularly cognitive behavioural therapy.

Conclusions

McDonald et al conclude by looking ahead to the development of autonomous online psychotherapy services that can be tailored to the needs of the individual patient and treatments that seek to be entertaining as well as therapeutic. They suggest that:

Themed interaction with another’s mind, through an internet programme, offers a fresh framework through which earlier negative experiences might be reconsidered, reappraised and restructured for future well-being.

Strengths and limitations

This article is a narrative review. This means that the authors did not systematically search the literature to identify all of the studies that might have been relevant, and they did not synthesise the results in a prescribed way or conduct a meta-analysis. However, they provided an engaging overview of the state of the field that was interesting to read and open access if you want to take a look yourself.

Implications for practice in the pandemic era

McDonald et al published their article in 2019, long before the outbreak of Covid-19. Mental health professionals fear that strict social isolation and in a lockdown, may lead to a tsunami of suffering from mental illness. It is unclear what form of psychotherapy may be most helpful to people suffering from the psychological consequences of pandemic restrictions.

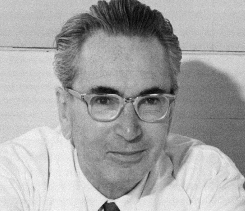

In my six decades of clinical practice, I saw many therapies come and go. Some, like insulin coma therapy and lobotomies, were rightly consigned to the history books. However, some useful modes of treatment have been neglected. In this respect, I am of the opinion that a little-known form of psychotherapy is of particular value in the COVID-19 epoch. It was developed by Viktor Frankl, and is known as the Third School of Viennese – the School of Logotherapy.

Frankl (1905 – 1997) was an Austrian Neurologist and Psychiatrist. He was Jewish. He and his family were deported to the concentration camps. His wife, father, mother and brother were killed. Not only did he survive, which was itself a miracle, but he helped others to survive too, by his psychotherapy, whose central idea is summed up in the title of his most famous book: ‘Man’s Search For Meaning’.

Viktor Frankl survived the concentration camps and agreed with Nietzsche that those who have a ‘Why’ can withstand any ‘How’.

Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy

Firstly, Frankl emphasised that in order to survive the hellish concentration camps, one needed a reason for living. Without that, you lost the will to live, and died. Frankl agreed with Nietzsche that those who have a ‘Why’ can withstand any ‘How’.

Secondly, Frankl also articulated that although the dehumanising conditions turned prisoners into walking dead, the prisoners had to keep their sense of identity. They had to realise that whatever possessions were taken from them, they still had the freedom to choose.

This speaks eloquently of the way that we can survive today. Individuals and families are facing grief, financial hardship and educational disruption added to the loneliness of social distancing. In our efforts to provide online psychological support we must help them to find a reason for continuing to live; to see that there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

Thirdly, Frankl highlights ‘that the most depressing influence of all was that a prisoner could not know how long his term of imprisonment would be. He had been given no date for his release.’ This has become a great issue in the present crisis, reflected in the constant questions regarding when lockdown restrictions may be lifted completely. Unfortunately, the answer is still in doubt, and honesty insists that we depend on the scientific data, which suggests that the danger may not pass for many months. This will be a cause of great tension to be addressed in any psychotherapy. Even as Frankl states, ‘With the end of uncertainty, there came the uncertainty of the end’. It is already clear that the world may never be the same again.

The Public Health Consultant, John Ashton, states that: ‘Historians in the future are likely to regard this global crisis as marking an end of an era and the beginning of a new one in which the new technologies will take centre stage. There will surely be total transformation of … the way we practise medicine … as we totally rebase. Our attitude to the meaning of life in the age of global threats to public health, of gross inequalities, of frivolous international travel, of the internet and social media.’

‘Hope springs eternal in the human breast’ – Alexander Pope.

Summary

- Online psychotherapy is gaining traction as a mental health intervention. As McDonald and colleagues described, it has a developing evidence base, particularly for CBT.

- COVID-19 is likely to increase the need for psychological support and makes face-to-face treatment difficult, therefore online options must be harnessed.

- Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy was born from the horrors of Auschwitz. His legacy can show us how to help our fellow human beings endure today’s crisis.

Statement of interests

I have no interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Jude Harrison for earlier comments on the manuscript.

Links

Primary paper

McDonald, A., Eccles, J., Fallahkhair, S., & Critchley, H. (2020) Online psychotherapy: Trailblazing digital healthcare. BJPsych Bulletin, 44(2), 60-66. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2019.66

Other references

Frankl, Viktor (1959). Man’s Search for Meaning. ISBN 9780807014295.

Logotherapy. Wikipedia. Accessed 19 May 2020 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logotherapy

Photo credits

- Photo by Samantha Borges on Unsplash

- Photo by visuals on Unsplash

- Photo by Ahmed Hasan on Unsplash

Fascinating, clearly written and so timely. Thank you David

What an inspiring and proactive piece of work.