“Doctors are always recommending me to give up smoking. They just say: “Do you smoke?” And I say yeah, and they said, “Give up”. And the nurses …they can give out patches but the only real advice they give is “Now really try this time. Really try”.

– Extract from service user interview (Knowles et al, 2016).

An important study is set to challenge an entrenched belief in many practitioners that people with severe mental illness (SMI) neither can, nor indeed wish, to stop smoking (Gilbody et al, 2019). Sally Adams covered the SCIMITAR pilot trial results back in 2015, but read on to find what the full study has today reported.

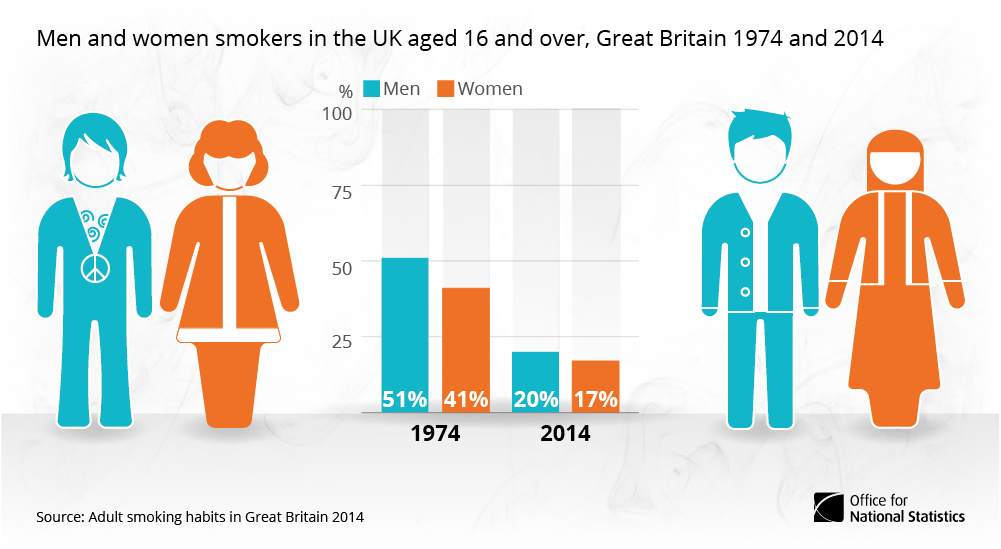

We know that the single greatest preventable cause of premature mortality in people with severe mental illness is smoking cigarettes (Brown et al, 2010). Public health policies and a focus on prevention of smoking-related diseases in primary care have seen general population smoking rates in the UK steadily fall over four decades from around 40-50% in 1974 to around 15% in 2017 alongside falls in daily cigarette consumption in those who do smoke. Yet for people with severe mental illness smoking rates remain stuck at 40-50% and most smoke heavily (Melzer et al, 2010).

Recently discharged psychiatric patients, or those in crisis services, have even higher smoking rates. What we do now to help smokers quit (nothing, or almost-nothing) is not working. The differences in mortality between people with SMI and the rest of us have got WORSE every year since the global financial crash, and UK austerity policies.

We know (at least) three things about smokers with severe mental illness:

- Most want to stop to protect their health, and often, their children’s health

- The high cost of tobacco eats into disposable income (“tobacco poverty”)

- Stop smoking programmes, that combine psychological support with medications, give all smokers the best chance of becoming permanently smoke-free.

The SCIMITAR+ trial (acronym warning: smoking cessation intervention for severe mental illness) tested this third hypothesis. They already knew that this group tend to smoke more than average smokers, and are more strongly addicted to nicotine. Discovering effective ways to help this vulnerable population to reduce or stop smoking is essential if this health inequality is to be tackled. Yet research to date has generally been small-scale, with few trials of behavioural interventions, no placebo-controlled trials of nicotine replacement therapy, and little research of how smoking cessation services should be organised (Peckham et al, 2017).

Current rates of smoking in people with severe mental illness are similar to those found in the general population in 1974.

Methods

Over 15 months, SCIMITAR+ recruited 526 people with SMI, aged over 18, who were living in the community. All had expressed a wish to quit smoking but were not in a stop smoking service. A computer programme randomised them into two groups: the trial group (behavioural treatments plus medications) and control group, meaning usual care under primary and mental health care. Researchers and clinicians could easily learn to which group each person was allocated, so this could not be a “double blind” trial where neither “subject” nor researcher know who gets what. Treatment was delivered mostly by smoking cessation-trained psychiatric nurses:

- Several assessments before quit date; up to 12 meetings (some had one)

- Offering nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) before that quit

- Advice to person and their clinicians about quit assistance drug, Varenicline (we know that psychiatrists hardly ever prescribe this, as in this study)

- Face to face support around quit time, including home visits

The control group also had access to standard offers: quit helpline and local stop smoking services (now a diminishing resource under cuts to public health) – researchers knew that people with SMI are less likely to attend these.

Both groups were followed up at 6 and 12 months. Smoking status was determined by a carbon monoxide monitor, and all participants filled out questionnaires throughout, too numerous to mention.

Results

526 participants recruited from 21 community mental health teams and 16 primary care sites across England were randomised to receive either a bespoke smoking cessation intervention (N=265) or care as usual (N=261). Documented diagnoses included schizophrenia (50%), other psychotic illness (15%), schizoaffective disorder (13%) and bipolar disorder (22%).

Most (96%) participants were recruited from community mental health teams; the remaining 4% came through primary care. Average age 46 yrs; 59% males, 41% females.

Participants typically had been smoking about 30 years. A majority reported that smoking adversely affected their health. A majority reported previously receiving advice from their doctor to stop smoking.

All outcome measures were assessed at baseline, 6 months and 12 months. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups.

The trial showed that people generally engaged with the bespoke intervention:

- 88% attended at least one quit smoking session

- The average number of sessions attended was 6.4 (SD 3.5)

- A session typically lasted about 35 minutes (range 5–120 mins)

The use of smoking cessation interventions was much higher in those receiving the treatment programme than in those receiving ‘usual care’.

The trial biochemically verified that at 6 months over twice as many patients receiving the bespoke smoking cessation intervention had quit. This result was statistically significant (OR 2·4, 95% CI 1·2 to 4·6; p=0·010).

However by 12 months, while results still favoured the intervention group, the difference in quit rates between the groups was no longer significant (OR 1·6, 95% CI 0·9 to 2·9; p=0·10).

The trial group did NOT gain weight, and improved on most mental health measures. These are two important findings: fear of gaining weight and the perception of poorer mental health in people who quit have become two obstacles to quit conversations.

The SCIMITAR+ bespoke smoking cessation intervention was successful in the short-term (6 months), but no longer statistically significant at 12 months.

Conclusions

David Shiers

Gilbody et al. found that people with severe mental illnesses more readily engaged a bespoke smoking cessation intervention than usual care, and were significantly more likely to quit smoking in the short term.

Although those receiving the intervention were still more likely to have quit, the difference was no longer significant by 12 months. The authors conclude that further research is needed to determine how long-term quitting can be supported.

Peter Byrne

The authors regret (as I do) how few were offered Varenicline; an effective drug against nicotine craving. Historical concerns about its mood effects, since disproved, have taken it from many doctors’ toolkits. Add to this, the potential for new generation electronic cigarettes to assist quitting, and I hope no one will conclude “why try?” when it comes to supporting people to quit. The authors point out that changes to local stop smoking services (and “changes” never means more resources these days) make the task of fewer people with SMI smoking even harder.

My take home message is that playing the long game will mean coproduction as standard care, and I want to see peer support workers paid to train, and work in, smoking cessation.

It’s time for the V-compromise: varenicline and vaping. Partnership with service users means resources for peer support workers.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- UK’s first large-scale randomised controlled trial to successfully combine a behavioural and pharmacological approach in a way that could meet the needs of people with severe mental illness

- Pragmatic design that facilitates real-world implementation into clinical practice

- Builds on increasing evidence for the safety and effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for nicotine dependence in people with severe mental illness.

Limitations

- 16% of participants were lost to follow-up. However attrition was equal across the study, making bias towards one study arm unlikely

- Some participants experienced difficulty obtaining pharmacotherapy due to changes in local commissioning arrangements. In some areas GPs were reluctant to prescribe nicotine replacement therapy because of smoking cessation services being contracted out to third parties where prescribing was conditional on participants enrolling into their service

- The study population was drawn from community patients and findings may not be generalisable to inpatient services

- The trial recruited a population likely to have had their psychiatric disorder for many years (although illness duration was not presented). The potential extra benefits for providing the intervention to people early in the course of psychosis, 59% of whom smoke (Myles et al, 2012), remains unexplored.

There was missing data for up to 41% of the trial, and the biggest single unknown was varenicline prescription.

Implications for practice

David Shiers

- The positive recruitment and retention to this trial is evidence in itself that people with severe mental illness are concerned about smoking and interested in finding effective ways to quit

- Practitioners should routinely ask their patients about smoking status and, if they wish, help them access effective smoking cessation services

- Health systems should provide smoking cessation interventions that are responsive to the needs of people with severe mental illness.

Peter Byrne

- All health professionals need to keep smoking at the top of every Problem List

- Bespoke interventions like SCIMITAR work, but need resources

- We have the drugs (NRT and Varenicline), our patients have the means (motivation, sometimes electronic cigarettes) to get this right. Local solutions must be made to work

- My conclusion is that peer support workers will help show the way, and support people with SMI to achieve a permanent quit.

Health systems should provide smoking cessation interventions that are responsive to the needs of people with severe mental illness.

Conflicts of interest

David Shiers was a member of the Trial Steering Group of SCIMITAR+ that provided trial oversight to the trial funders and sponsors on matters such as ethical approval, safety of trial participants, trial progress, and adherence to protocol. David is an expert advisor to the NICE centre for guidelines and a member of the current NICE guideline development group for Rehabilitation in adults with complex psychosis and related severe mental health conditions; Board member of the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH); views are personal and not those of NICE or NCCMH.

Peter Byrne is on the clinical advisory group of Equally Well, contributed to ASH Stolen Years Report, and wrote the RCPsych Position Statement on Varenicline and Vaping. He has never accepted, or would accept funding, from manufacturers of electronic cigarettes or varenicline, or Big Tobacco, obviously.

Links

Primary paper

Gilbody S, Peckham E, Bailey D, Arundel C, Heron P, Crosland S, Fairhurst C, Hewitt C, Li J, Parrott S, Bradshaw T, Horspool M, Hughes E, Hughes T, Ker S, Leahy M, McCloud T, Osborn D, Reilly J, Steare T, Ballantyne E, Bidwell P, Bonner S, Brennan D, Callen T, Carey A, Colbeck C, Coton D, Donaldson E, Evans K, Herlihy H, Khan W, Nyathi L, Nyamadzawo E, Oldknow H, Phiri P, Rathod S, Rea J, Romain-Hooper C, Smith K, Stribling A, Vickers C. (2019) Smoking cessation for people with severe mental illness (SCIMITAR+): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30047-1

Other references

Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, et al. (2010) Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196: 116-121.

Knowles , Planner C, Bradshaw T, Peckham E, Man M, Gilbody S. (2016) Making the journey with me: a qualitative study of experiences of a bespoke mental health smoking cessation intervention for service users with serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry (2016) 16:193

McManus S, Meltzer H, Campion J. (2010) Cigarette smoking and mental health in England. Data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. National Centre for Social Research; 2010.

Myles N, Newall, HD, Curtis J, et al. (2012) Tobacco use before, at and after first-episode psychosis – a systematic meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2012: 73: 468-475.

Peckham E, Brabyn S, Cook L, Tew G, Gilbody S. (2017) Smoking cessation in severe mental ill health: what works? An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:252

Office for National Statistics (2016) 40 Years of Smoking. March 9th 2016 (Website accessed 4/4/19).

Useful links

RCPsych (2018) The prescribing of varenicline and vaping (electronic cigarettes) to patients with severe mental illness: position Statement on Varenicline & Vaping. Royal College of Psychiatrists

ASH (2016) Stolen Years Report.

Photo credits

- Office for National Statistics (2016) 40 Years of Smoking.

- Photo by Finn Gross Maurer on Unsplash