In recent years there has been a significant increase in the use of mobile phone and digital interventions for mental health. A quick search of ‘mental health’ in the Apple App Store reveals over 90 apps from a variety of providers, which aim, variably, to assist with management of mental health needs, provide education on mental health and wellbeing or deliver a digital form of counselling or coaching. It is particularly refreshing to see technology used in such an innovative way in the face of media reports which claim that social media and digital technology may be harmful to mental health.

For digital health interventions (DHIs) to be successful, it is vital to capture the views of those that will be most instrumental in implementing them; namely, mental health staff in a variety of roles. Previously it has been reported that mental health staff indicated largely neutral or positive attitudes towards the use of digital health interventions for the management of mental health problems (Carper et al., 2013; Pierce et al., 2016; Schueller et al., 2016). Despite this, staff have also highlighted some potential issues with the use of digital health interventions, and in particular appear hesitant to encourage their use in clients with complex needs (Sinclair et al., 2013). This highlights the need to explore staff views of digital health interventions in more detail, particularly in the context of severe and complex cases.

The aims of a recent qualitative study (Berry et al, 2017) were to:

- Investigate the experiences and views of mental health care staff toward clients with severe mental health problems using the internet and mobile phones to manage their mental health

- Explore opinions expressed by mental health care staff toward digital health interventions for severe mental health problems to identify the potential facilitators and barriers to the implementation of digital health interventions in mental health care services

The use of digital technology for mental health has grown significantly in recent years, despite claims that social media and technology could be harmful to mental health.

Methods

The authors ran four focus groups with 20 NHS mental healthcare professionals in the North West of England, which included staff from: psychological services, community mental health teams and rehabilitation units. The mean age of participants was 42.35 (range 27-62) and participants were predominantly White British (80%) females (80%).

Questioning in the focus groups focussed on two key areas:

- Staff’s experiences of clients use of the internet and mobile phones

- Staff’s views about the acceptability of implementing DHIs for severe mental illness in mental health care services.

To prevent the research team’s experiences affecting their analysis and interpretation of the data, the lead researcher kept a reflective journal detailing how staff responses in each focus group affected her own views, and took this into account when analysing the data. The data were analysed thematically using a cyclical process.

Results

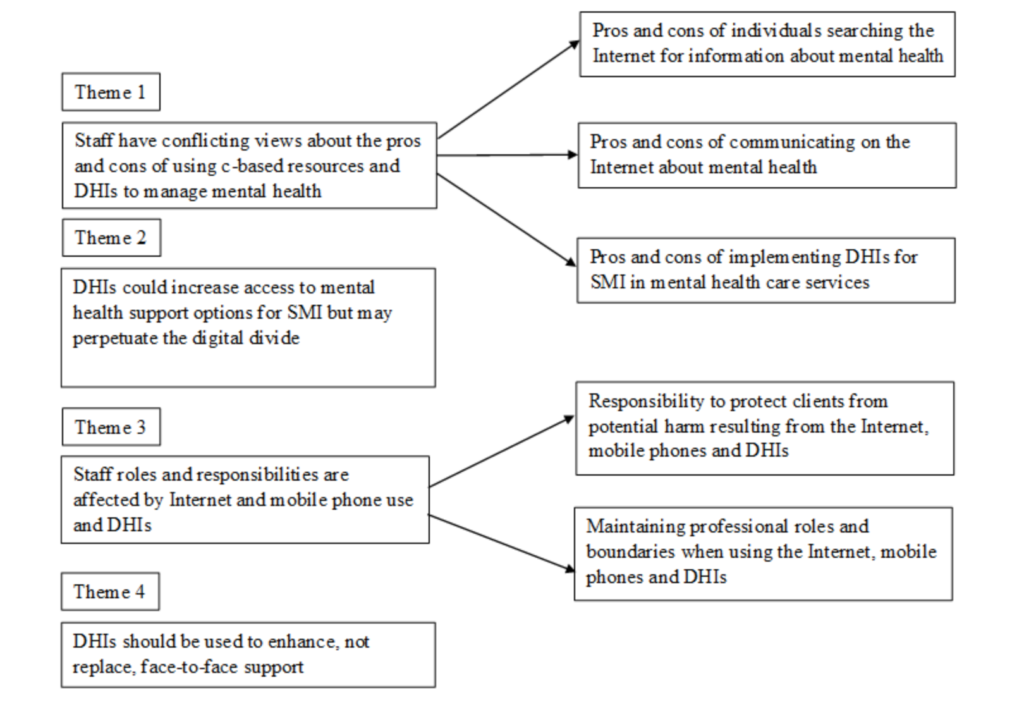

The analysis revealed a total of four themes and five sub-themes. These are outlined below in a diagram of themes lifted from the original paper.

1. Staff have conflicting views about the pros and cons of using web-based resources and digital health interventions to manage mental health

1a. Pros and cons of individuals searching the internet for information about mental health

Staff felt that it was good for people to search the internet for mental health information because it meant they could access information at any time and place, which was felt to be helpful before beginning therapy. Staff also felt that web-based resources could be helpful during sessions and drew on their experiences of using resources such as YouTube videos to help normalise client’s experiences. Finally, staff noted that they themselves often used the internet for information about their own mental health and therefore empathised with clients who were doing the same. For this reason, staff felt it was important for psychoeducation to be included in future DHIs.

Despite these favourable views, staff also raised some concerns, noting that clients would be likely to access unregulated web-based material which could be biased, inaccurate and misleading and may lead to harmful or damaging behaviours. It was felt that clients could be vulnerable and did not have the training or experience that staff did to filter out potentially biased or inaccurate information. Further, staff raised issues with the specific content of material, for instance stating that content relating to religion, conspiracy theories and anti-psychiatry messages could all reduce engagement with services and medication.

1b. Pros and cons of communicating on the internet about mental health

Staff in all focus groups were able to recall experiences of clients receiving helpful support from peers via web-based forums and social media websites. Staff felt that these experiences were positive due to the anonymous nature of these forums, and their ability to connect people with similar experiences which made clients feel more comfortable expressing themselves than they perhaps would in person. Staff also noted that severe mental illness can lead to social isolation, e.g. being unable to leave the house or not feeling comfortable speaking to people face to face. Communicating online was therefore perceived to overcome some of these barriers and went some way to enabling clients to feel connected.

Despite some staff stating that the anonymity of web-based forums was a positive factor, others felt that this could cause concern. For instance, it was posited that the anonymous nature of these forums meant that users were often not aware of the consequences of negative messages, and therefore clients were at a greater risk of being bullied, trolled or taken advantage of. Further to this, staff were concerned that client’s may disclose too much personal information online which could lead to embarrassment, distress and others targeting and taking advantage of them. This was thought to be a particular issue in the communication of messages surrounding self-harm and suicide. Staff suggested that NHS should offer moderated forums for clients to engage with to overcome some of these concerns.

1c. Pros and cons of implementing digital health interventions (DHIs) for severe mental illness in mental healthcare services

Staff, again, praised the anonymous nature of DHIs which they felt could enable clients to feel more comfortable disclosing sensitive information, particularly as this disclosure was perceived to pose less risk in regards to other people being able to access copies of their therapy materials. The other main benefit discussed was the use of DHIs to monitor symptoms, which staff noted could be of extreme utility in sessions when clients could not remember how they’ve been feeling since their last session.

In direct contradiction to the view that there was a reduced risk of others accessing client’s sensitive information, some staff raised concerns that companies or individuals may hack digital devices and obtain sensitive information, a view which fits in with the context of the recent NHS system hacking. Again, in direct contrast to staff praising the anonymity of DHIs, others felt that this could lead clients to under- or over-report symptoms with a view to reduce or increase the level of care they receive. Finally, staff were worried that symptom monitoring could become tiresome for clients and lead them to dwell on negative experiences. Staff therefore advocated that symptom monitoring should include a focus on positive experiences as well as negative ones.

Staff held conflicting views about the pros and cons of searching online for mental health information, communicating about mental health online and implementing digital health interventions.

2. Digital health interventions (DHIs) could increase access to mental health support options for severe mental health problems, but may perpetuate the digital divide

Despite staff acknowledging that internet and mobile phone use was very much the norm, especially for young people, there was still a concern from staff that some people did not have the technology skills required to use DHIs. Further to this, it was noted that not everybody had access to the internet or mobile phones. Both of these access issues were thought to pose significant barriers to implementation.

Whilst staff advocated the provision of skills training courses to help clients gain the necessary technology skills required to use DHIs, they felt strongly that the NHS should not provide clients with access to the technology itself required to access DHIs (e.g. mobile phones, tablets). Staff felt that limited money should be spent on other interventions (e.g. medication) and also raised concerns that devices may be lost, sold or damaged.

Despite staff’s concerns over the access to DHIs, participants in all focus groups were able to identify experiences of clients successfully accessing digital devices to self-manage their mental health. For instance, staff recalled clients:

- Accessing information about medication, diagnoses, symptoms, personal stories and coping strategies

- Using forums and social media websites to discuss mental health

- Using mobile phone cameras to photograph formulations during therapy sessions

- Using alarms and calendars on mobile phones for appointment and medication reminders

- Using apps to receive already existing self-management options.

Staff raised concerns that digital health interventions may perpetuate the digital divide.

3. Digital health interventions impact on staff roles and responsibilities

3a. Responsibility to protect clients from potential harm

Staff raised concerns that clients were vulnerable to over-disclosure online, and were fearful that clients would access inappropriate content such as extreme beliefs, antipsychiatry messages, pornographic material and gambling websites, which could exacerbate symptoms and decrease engagement with services. Because of this, most staff felt that the use of digital devices should be monitored by staff, with staff being responsible for limiting and controlling the websites and apps that could be used, and conducting risk assessments before allowing access.

Further to this, staff were worried about their moral, legal and professional obligations to assess risk information such as suicide ideation and behaviour if clients were monitoring symptoms via digital devices. Because of this, staff did not advocate the automatic communication of monitored symptoms to them but instead felt that clients should bring their own symptom reports to appointments. This was felt to reduce the level of burden and responsibility on them whilst simultaneously empowering the client and giving them control over the information they choose to share.

3b. Maintaining professional roles and boundaries

Staff exerted mixed views on the exchange of SMS messages to clients. Whilst some had sent appointment reminders to clients, and shared their personal mobile phone numbers to clients (with the understanding that there were limits on when clients could contact them), others were concerned about breaches in data confidentiality and the risk of clients contacting them outside working hours.

Participants in all focus groups agreed that it was a misuse of trust and power to monitor client’s social media profiles for information about daily functioning and risk. Staff spoke about this particularly emotively and asserted that it could damage the therapeutic relationship.

Staff felt strongly that monitoring client’s social media profiles for information about daily functioning and risk was a misuse of their trust.

4. Digital health interventions should be used to enhance, not replace, face-to-face support

Whilst staff viewed DHIs as empowering and a unique way for clients to take control and responsibility for their own mental healthcare, they also said that DHIs should not be offered as an alternative to traditional face-to-face support. Staff felt that DHIs could not mimic the important therapeutic relationship between staff and clients, and also felt DHIs were unable to deliver interventions in the same personal way in which staff worked.

However, staff did feel that DHIs could be used to help extend the support options available to clients. Staff suggested numerous ways in which this could be done:

- App-based symptom monitoring could be used by services for routine outcome monitoring

- DHIs could be used at the end of therapy to allow clients to access coping mechanisms and strategies developed in sessions

- Community mental health team members could offer home visits to support them working with DHIs, to ensure that clients were not left to deal with their issues alone.

Digital health interventions should be used to extend, not replace, traditional face-to-face interventions.

Conclusions

A number of key messages can be deduced from this paper which point towards some of the potential barriers and facilitators of implementing DHIs for severe mental health.

First, the anonymity granted by the internet was generally viewed as a positive factor of DHIs. Staff felt that this anonymity enabled clients to feel more comfortable disclosing sensitive information, in terms of symptom monitoring and also in terms of connecting with other people in similar situations to themselves. This added benefit that a digital intervention brings could therefore be viewed as a facilitator to implementation.

Second, staff raised concerns about the unregulated content of both information found on the internet and forums used to communicate about mental health. Clients were generally viewed as vulnerable and staff feared that they would not have the ability to filter biased information, would over disclose personal information, and could be targeted by others. Staff adopted a somewhat paternalistic view in asserting the need for client’s access and use of online resources to be monitored and limited where appropriate.

Third, staff noted that access to DHIs could pose a barrier and even perpetuate the digital divide, with some clients not possessing either the skills or technology needed to benefit from such resources. Despite this, staff acknowledged and detailed the ways in which clients were already using digital devices to manage their mental health needs, which could be taken as a facilitator to the implementation of DHIs.

Fourth, it was posited by staff that the introduction of digital resources could change the role of the therapist. For instance, sending text messages to clients could remove the professional boundary between staff and client. Further to this, it was felt that DHIs would lose the important therapeutic relationship and also may omit the personal touch that staff currently bring to therapy. Despite this, staff gave a number of suggestions for how DHIs could be used to extend the support currently given, which again could be taken as a facilitator to the implementation of DHIs.

Strengths and limitations

The authors should be commended for their rigorous application of qualitative methods. The reflexive journal kept by the lead author indicates the research team’s strong commitment towards maintaining objectivity and scientific rigour, a basis for which qualitative research is often criticised.

Despite this, the paper is not without its limitations. Focus groups were conducted in already established work teams, including the service lead in each team. This may have made participants feel uncomfortable about expressing their true and honest opinions. Conversely, taking part in the study as part of a pre-established peer group may have enabled participants to communicate more freely, as part of a trusted group.

Again, the use of a reflexive journal should be commended here, as the authors were able to use this to assess the group dynamics of each focus group. Review of the reflexive journal indicated that there were no issues with participant’s level of comfort in sharing their views and experiences.

Summary

This paper has illustrated that staff had a wide range of positive and negative experiences of clients using the internet and mobile phones for self-management of mental health needs. Further to this, it appears that staff were cautious, but optimistic, about the implementation of DHIs.

The present paper provides the much-needed, rich and detailed views and experiences of staff around clients use of internet and mobile phones to manage their mental health needs. This paper is of clear utility for those working in NHS mental healthcare services who are interested in how DHIs may help or hinder the provision of mental healthcare to those with severe mental health needs.

Mental health staff were cautious but optimistic about the implementation of digital health interventions for people with severe mental illness.

Links

Primary paper

Berry N, Bucci S, Lobban F. (2017) Use of the Internet and Mobile Phones for Self-Management of Severe Mental Health Problems: Qualitative Study of Staff Views. JMIR Ment Health 2017;4(4):e52 DOI: 10.2196/mental.8311

Other references

Carper et al. (2013) The dissemination of computer-based psychological treatment: A preliminary analysis of patient and clinician perceptions. Admin Policy Ment Health; 40(2): 87-95.

Pierce et al. (2016) Perspectives on the use of acceptance and commitment therapy related mobile apps: results from a survey of students and professionals. J Contextual Behav Sci; 5(4): 215-224.

Schueller et al. (2016) Exploring mental health providers’ interest in using web and mobile-based tools in their practice. Internet Interventions; 4(2): 145-151.

Sinclair et al. (2013) Online mental health resources in rural Australia: clinician perceptions of acceptability. J Med Internet Res; 15(9): e193.

Photo credits