In recent years the number of digital or e-health solutions developed for stress management have risen substantially. The promise of cost-effective, individualised ways of helping people to reduce stress has taken flight in several sectors including business and healthcare.

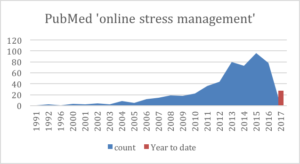

In addition, the scientific community has taken an interest in online stress management.

A quick search on PubMed, for example, shows a rising trend in the peer-reviewed literature (see figure below).

However, the overall impact of web and online interventions on stress, anxiety and depression is still unknown.

A recent meta-analysis published in the Journal for Medical Internet Research aimed to address these questions by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis.

More specifically, the research questions were:

- Are online stress management interventions effective in reducing stress, depression and anxiety compared to control?

- What types of interventions (theoretical basis, length and guidance) are more effective (and for whom)?

- Does study quality affect the relative effect size?

Can you manage stress effectively on your computer or the web?

Methods

PsychINFO, Cochrane and PubMed were searched with comparable search strings. Randomised controlled studies published between 1990 to 2016 were included, as digital products developed before 1990 are likely to be non-reflective of the current online landscape. Interventions focussing only on wellbeing were excluded and the studies needed to have at least one outcome measure relating to stress.

Results

2137 studies were found. In total 94 studies were screened in full text and 23 randomised controlled studies were included in the meta-analysis.

- The overall mean effect size for stress was Cohen’s d=0.43 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.54)

- Some additional significant but small effect sizes were found for:

- Depression (Cohen d=0.34, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.48)

- Anxiety (Cohen d=0.32, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.47)

Subgroup analyses results

Theoretical basis

The included studies are displayed in a helpful table 2 in the paper. To summarise most studies used third wave CBT techniques (13) studies and after that alternative interventions were mostly seen (7 studies) with CBT interventions present in 6 studies.

- Third Wave CBT includes interventions such as acceptance and commitment treatment, behavioral activation, and mindfulness-based approaches. In this study most of these interventions used mindfulness based exercises or problem solving and emotional regulation techniques to manage stress. For more information on Third wave CBT please see further info in another mental elf blog by fellow elf Mark Horowitz.

- Alternative interventions included present control interventions or use of olfactory products.

In terms of results for theoretical basis of the interventions, a subgroup analysis found that third wave CBT showed a significant effect size of Cohen d=0.53 (95%CI 0.35 – 0.71 n=13).

CBT interventions had a significant effect size of Cohen d=0.40 (95% CI 0.19-0.61; n=6).

Alternative interventions had a smaller, but positive, effect of Cohen d=0.24; (95%CI 0.12 – 0.36 n=7).

Length of intervention

- Short to medium size interventions produced small to medium effect sizes whilst long interventions were non-significant.

Duration of effect

- 4 to 6-month follow-up showed medium effect size whilst 1 to 3 moth follow up had a small effect size. It is important to note that not all studies included had these longer follow up times so this analysis was done on a smaller sample.

This well conducted review suggests that digital stress-management interventions can be effective and have the potential to reduce stress-related mental health problems on a large scale.

Conclusions

To refer to the main questions:

Are online stress management interventions effective in reducing stress, depression and anxiety compared to control?

- The analysis found that, yes a moderate effect size was found, with effects for up to 6 months.

What types of interventions (theoretical basis, length and guidance) are more effective (and for whom)?

- Guided interventions were more effective than unguided interventions. It’s important to highlight that guided studies were in the minority with just 7 out of 23 interventions having some form of guidance.

- Third wave CBT and CBT were moderately effective, whilst alternative interventions provided a small, but positive effect.

- Short and medium interventions (defined as up to 8 weeks) were more effective than longer interventions.

Does study quality affect the relative effect size?

- Yes, the study quality did affect the results, with low risk of bias studies having larger effect sizes compared to studies with some risk.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This is a high quality meta-analysis that clearly highlights the challenges in summarising a heterogenous pool of studies and interventions. It is generally challenging to categorise studies effectively and I think this has been done quite helpfully, which therefore provides good practical recommendations for clinicians and patients.

Limitations

There was quite some overlap between studies and the comparisons made, and a relatively small number of studies included in some of the comparisons that were made. The most common intervention type was third wave CBT, with thirteen studies assessing the effectiveness of this type of therapy on reducing stress. It may be that other, alternative interventions also work but there is limited rigorous research available on these interventions.

It is also important to note that these results only count for the studies and interventions included. Thus, although these results are positive it is likely that the results are different for interventions not included in this analysis.

Most studies came from the USA, with one from the UK. Although there are cultural similarities, it is important to keep in mind that not all findings may directly translate to a UK setting. The studies were also quite different from each other in terms of follow up period, and risk of bias was present in all studies.

Future research is needed into the cost-effectiveness of digital interventions and ideally future studies should take this into account to help build a case for business and local government.

Future research is needed into the cost-effectiveness of digital interventions.

Implications for practice

I think this study provides a positive case for offering stress management on a large scale and a good insight into the current state of the evidence for online stress reduction. However, there is also room for improvement. On the whole, and as the authors highlight, more rigorous low risk of bias studies are needed.

In addition, future research could look at:

- What works for whom

- How to best support implementation

- What personal characteristics support adherence.

If this is of interest, a recent study by Zarski et al. (2016) could be an informative read on the topic.

Another crucial point to note is that there is little evidence on the longer-term effects of e-mental health interventions. This is also the case in this meta-analysis where only 3 studies had a follow-up of one year or longer. Hence, we are not sure what the longer-term preventative effects of these interventions may be and future studies should aim to have longer follow up.

In addition, there is a need to strengthen research for e-mental health on the whole, this includes looking at effectiveness for different population groups, new ways of evaluating effects of digital mental health and effective ways to co-produce and include user views and perspectives into the evaluation of digital mental health products.

To help set priorities for research, a James Lind Alliance Digital Mental Health priority setting partnership has been set up to find the top 10 research questions for digital mental health. The survey which is aimed at people with lived experience of mental illness, their carers and health professionals, is open until the end of June.

To help address implementation, evaluation and scaling issues relating to digital mental health, the Mental Health Foundation is part of an innovation and transnational implementation platform across North West Europe (the eMEN project). This is led by Stichting Arq in the Netherlands, which looks to improve implementation of e-mental health interventions across Europe. You can read the eMEN project summary or follow the project on twitter @eMEN_EU.

Complete this 1 question survey to help define the top 10 digital mental health research questions.

Conflicts of interest

I work for the Mental Health Foundation. I am part of the eMEN project. I collaborate with the authors of this paper (from the VU Amsterdam) but had no involvement in this specific piece of work.

Links

Primary paper

Heber E, Ebert DD, Lehr D, Cuijpers P, Berking M, Nobis S, Riper H. (2017) The Benefit of Web- and Computer-Based Interventions for Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2017 Feb 17;19(2):e32. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5774.

Other references

[…] This article looks at evidence about online stress programmes. It suggests that guided online interventions based on CBT are effective. It uses the term “Third Wave CBT” to use the form of CBT commonly employed in these contexts. Third Wave CBT makes use of mindfulness. It focuses on the process rather than the content of thought. We’ve been struggling in revision lessons to come up with a sound and clear description of CBT. The descriptions we have managed now seem out of date. […]

[…] Digital interventions for stress: do they live up to their alleged potential? […]