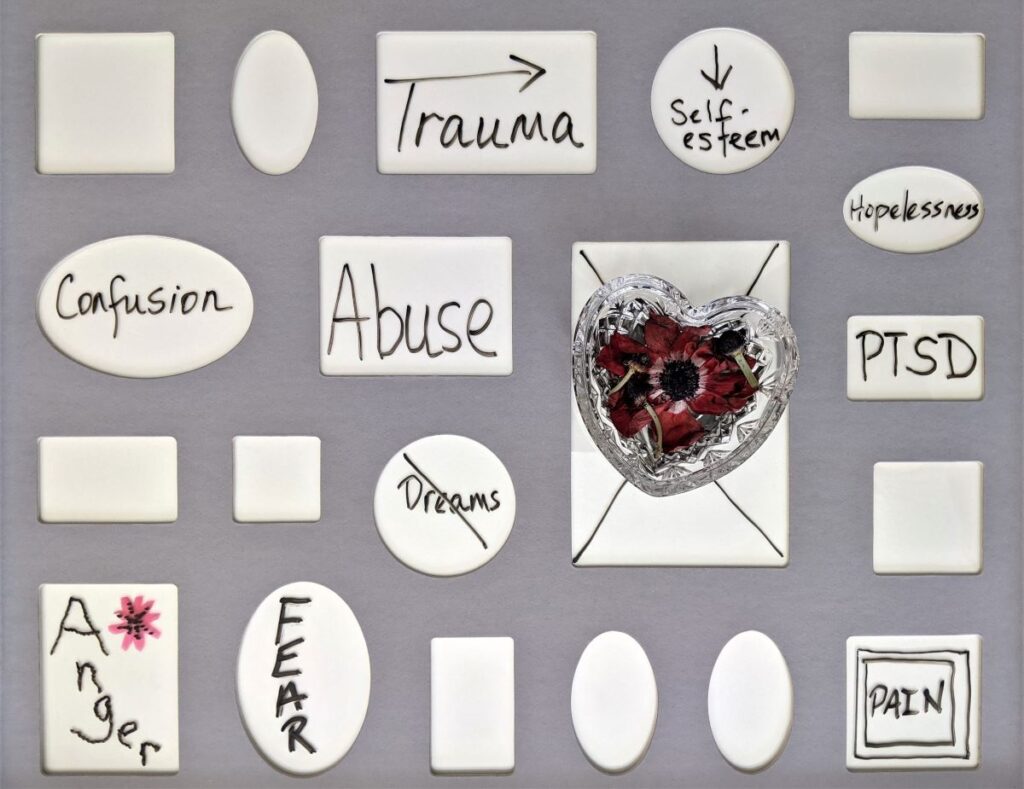

Complex PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is a new diagnosis in ICD-11 (World Health Organisation, 2018). It was first conceptualised in 1992 by Judith Herman, to describe psychological reactions to trauma that were not captured by the existing diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder: somatization, dissociation, emotional dysregulation (depression, anger, suicidality), and relationship disturbances (oscillating between intense attachment and terrified withdrawal), alterations in identity and systems of meaning (the self as contaminated and guilty, lack of personhood, fragmented sense of self) (Herman 1992). (If the reader thinks this description bares a striking similarity to “borderline personality disorder” then they are not mistaken). The syndrome was also called “Disorders of Extreme Stress Not Otherwise Specified” by van der Kolk and colleagues. Herman linked these psychological reactions specifically to “complex trauma”, by which she meant prolonged, repeated trauma, usually in the context of coercive control by another person/ persons.

Since then, the construct of complex PTSD has evolved. Arguably, one reason for this evolution was that the complex PTSD conceptualised by Herman and van der Kolk was not accepted into DSM-V (published by the APA in 2013). It was deemed flawed for a number of reasons, including significant overlap with PTSD, borderline personality disorder, and depression (Resick et al. 2012). The construct that made it into ICD-11 is broader in some ways, and narrower in others, than the original conceptualisation. Firstly, the “disturbances of self-organisation” characteristic of complex PTSD have now been narrowed down to three: “severe and pervasive problems in affect regulation, persistent beliefs about oneself as diminished, defeated or worthless and persistent difficulties in sustaining relationship and feeling close to others.”

Secondly, the person must also meet diagnostic criteria for ‘classic’ PTSD (re-experiencing symptoms e.g. flashbacks, nightmares; avoidance of trauma reminders; persistent perception of heightened current threat) (Briere et al. 1995).

Thirdly, the construct has been broadened as it was realised that single traumatic events could also lead to psychological reactions characteristic of complex PTSD (Brewin 2020). Therefore, type of trauma is no longer relevant to whether PTSD is considered “complex” or not. However, the ICD-11 does recognise that complex PTSD is more likely to occur following prolonged or repetitive traumatic events from which escape is difficult or impossible (World Health Organisation 2018).

The evolution of the construct has led to its successful inclusion in ICD-11; however, very little research has been undertaken looking at how best to help people who meet these new refined criteria for complex PTSD, since the final definition has only recently been agreed. Therefore, researchers need to look for clues in existing research with trauma survivors.

Complex PTSD has recently been recognised as a diagnosis. It refers to psychological reactions to trauma that were not captured by the existing diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Methods

Thanos Karatzias and colleagues carried out three systematic reviews and meta-analyses to try to find out what works best for helping people with complex trauma and/or complex PTSD. A systematic review is when researchers search for all published and unpublished research on a certain topic. The meta-analysis is where they pool the results of all the studies they find to crunch the numbers and come up with an “averaged” finding across studies. Because large studies tend to be more trustworthy than small studies, researchers give more weight to numbers from larger studies. This is helpful because individual studies are small and based on select samples, so it’s harder to be confident that what they found represents the truth. By pooling the numbers across similar studies, we can be more confident in the overall conclusion.

In two of the meta-analyses, the authors focussed on people who had experienced complex trauma. In one study this was defined as trauma that was extreme and prolonged or repetitive in nature and experienced as extremely threatening or horrific and difficult or impossible to escape from (Coventry et al. 2020); in the other this was defined simply as interpersonal trauma i.e. involving threat or violence from another person/ people (Mahoney et al. 2019).

The third meta-analysis focussed on people with difficulties akin to the ICD-11 diagnosis of complex PTSD (Karatzias et al. 2019). Importantly, because complex PTSD has been so understudied and its precise conceptualisation in ICD-11 is very new, they were not able to determine whether study participants met criteria for complex PTSD. Instead, they used an “analogue” or “proxy” definition to find people who were experiencing a similar set of difficulties. They did this by looking for people who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, and who also had at least one of the “disturbances in self-organisation” linked to ICD-11 complex PTSD i.e. emotion dysregulation, negative self-concept, and disturbed relationships. Consistent with the ICD-11 conceptualisation of complex PTSD, the authors included studies in which participants had experienced a range of different types of trauma, including both interpersonal trauma (such as abuse) and non-interpersonal trauma (such as natural disasters).

Results

Two of the reviews included only randomised controlled trials (Karatzias et al. 2019, Mahoney et al. 2019); the third included some non-randomised trials (Coventry et al. 2020). “Non-randomised” means that whether a person received the intervention or the comparator treatment was not decided at random. This makes it harder to avoid biases in who gets what treatment, which can skew the results. If randomisation is not done properly this can also skew the results; all three reviews complained that some study authors did not publish enough information for them to be able to assess this.

For people with a history of complex trauma (Coventry et al. 2020)

- Psychological treatments were found to be helpful for treating PTSD, anxiety, and depression and improving sleep

- Psychological treatments that focussed on processing the trauma, such as trauma-focussed CBT and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), seemed to be most helpful of all for treating PTSD (although slightly less helpful for veterans and war-affected populations)

- Medication was less effective than psychological interventions for treating PTSD symptoms and improving sleep.

Looking specifically at group therapy for people with a history of complex trauma (Mahoney et al. 2019)

- Group therapies involving processing the trauma were more helpful than usual care for improving depression, PTSD symptoms and psychological distress

- There was some indication that trauma-processing group therapies may be more helpful than psychoeducation for improving PTSD symptoms, whilst psychoeducation may be more helpful for improving depression and psychological distress. However, this finding was statistically nonsignificant (i.e. uncertain and may have occurred by chance).

Finally, for people with PTSD who were experiencing at least one aspect of the “disturbances in self-organisation” consistent with complex PTSD (Karatzias et al. 2019)

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), exposure therapy, and EMDR were found to be more helpful than usual care for improving PTSD symptoms

- Both CBT and EMDR were more helpful than usual care for improving emotion dysregulation, negative self-concept and disturbed relationships

- Exposure therapy was more helpful than usual care for improving negative self-concept and disturbed relationships, but no studies had measured its effect on emotion dysregulation

- Some of the positive findings on EMDR came from a single study, so caution is warranted as the findings require replication

- The authors found that psychological interventions were less helpful (but still helpful overall) for people whose trauma had occurred in childhood, compared to people who had only experienced trauma in adulthood.

Across the three meta-analyses, findings from 181 studies were evaluated. They all pointed towards trauma-processing therapies as being key.

Conclusions

Across these three meta-analyses, some common threads stand out. For people who have experienced complex trauma, and/or who have symptoms of complex PTSD, interventions focussed on processing the trauma seem to be helpful. Talking about what happened, making sense of it and understanding its impact, can help. When trauma is complex, sometimes the prospect of working through what happened can feel too daunting to contemplate. Clinician and survivor alike can sometimes fear that it will be too much to bear. But the data seems to suggest that – on average – facing what happened head on seems to help. However, there are still large gaps in our understanding of the helpfulness of this approach.

There’s also some preliminary evidence that processing the trauma can help with the “disturbances of self-organisation” linked to complex PTSD. However, it is clear that we don’t know enough about what helps with this as not enough studies have been conducted.

Talking about what happened can help people with complex PTSD, but there is more we still need to understand.

Strengths and limitations

The reviews were all conducted using rigorous systematic review and meta-analytic methodology. The authors worked hard to ensure no stone was left unturned in their search for relevant data, including having multiple people independently comb through their search results and data to ensure that any oversights by one person could be corrected by another pair of eyes.

The main limitation, acknowledged by the authors themselves, has been highlighted earlier in the blog. Namely that – due to the novelty of the complex PTSD diagnosis and the evolution of the construct over time – very little research has been conducted evaluating psychological interventions for people explicitly identified as having complex PTSD as defined in ICD-11. Instead, the authors had to use proxy measures – either people exposed to complex trauma (but without being sure that they met diagnostic criteria for complex PTSD), or people with classic PTSD who seemed to have at least one aspect of the complex PTSD “disturbances of self-organisation”. Future research should overcome this limitation by evaluating psychological interventions for people who clearly meet diagnostic criteria for complex PTSD.

Additionally, the inclusion of non-randomised studies in one of the reviews makes it harder to avoid biases in who gets what treatment, which can skew the results. If randomisation is not done properly this can also skew the results; all three reviews complained that some study authors did not publish enough information for them to be able to assess this. Overall, Coventry et al. (2020) assessed 37% of the studies they included as being at low risk of bias, 23% as at moderate risk of bias, and 39% as at high risk of bias. Karatzias et al. (2019) assessed 34% of the studies they included as of moderate quality, 38% as low quality, and 28% as very low quality. Finally, Mahoney et al. (2019) complained that only 3 of the 36 studies they included presented a low risk of bias. The included studies fell down on issues such as not using a structured clinical interview to diagnose PTSD, not reporting whether the intervention was delivered with fidelity to the treatment model, and not being clear about how they conducted follow-up assessments.

These 3 rigorously conducted systematic reviews from 2019-2020 are limited by a lack of clarity in what defines complex PTSD.

Implications for practice

Overall, the findings indicate that trauma-focussed interventions may be helpful for people experiencing complex PTSD. However, many questions remain.

A common debate in thinking about complex PTSD is whether phased interventions are needed, whereby emotion dysregulation and other disturbances in self-organisation are addressed first, before only later moving on to explicitly explore trauma (Cloitre et al. 2012). The rationale is to increase emotional, psychological and social resources to improve functioning in daily life, and secondly, to use these resources to enhance the effectiveness of trauma-focused work. However, others have argued this could lead to unhelpful delays in using more trauma-focused interventions (De Jongh et al., 2016). The authors of the reviews lament that, due to the lack of evidence on phased interventions, it is not yet possible to say whether phased interventions are more or less helpful than non-phased interventions. They also suggest that future research could evaluate whether attachment-based and relational therapies are helpful for the disturbances in self-organisation linked to complex PTSD. They recommend that further work may be needed to improve intervention for people with a history of childhood trauma, since existing interventions seemed on average less effective for this group.

Finally, the review authors suggest that more evidence should be gathered on the safety of trauma-focussed interventions, since there have been concerns that for some people with complex PTSD these could exacerbate emotional dysregulation and lead to increased self-harming behaviour. Reading this made me reflect on my own work with individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder who also had PTSD, of whom 74% also met criteria for probable complex PTSD. They were offered dialectical behaviour therapy with prolonged exposure for PTSD. This is a phase-based approach as described above, whereby dialectical behaviour therapy was offered first, and then, once a person is able to stop self-harming and increase their emotion regulation skills, they are offered a trauma processing treatment called prolonged exposure. It has previously been shown in the US to be safe and effective (Harned et al. 2014). However, in our UK evaluation, we found that whilst 60% of participants said they would try prolonged exposure if offered, only 35% of these have received it and only 43% of these completed it. Interviews with patients and therapists suggested that some patients found it very helpful whilst others struggled to tolerate the distress of going over the trauma in depth. Speaking with the therapists, it was clear that delivering trauma-focussed interventions can be challenging, and that expert therapist supervision and team support is crucial. Further research should investigate the contextual factors that are important for successful delivery of trauma-focussed interventions for people with complex PTSD, such as access to expert supervision and team support.

Complex PTSD – many questions remain, such as the potential harms of therapy on some patients.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary papers

Coventry PA, Meader N, Melton H, Temple M, Dale H, Wright K, Cloitre M, Karatzias T, Bisson J, Roberts NP, Brown JVE, Barbui C, Churchill R, Lovell K, McMillan D, Gilbody S. (2020). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Med.19;17(8):e1003262.

Karatzias T, Murphy P, Cloitre M, Bisson J, Roberts N, Shevlin M, Hyland P, Maercker A, Ben-Ezra M, Coventry P, Mason-Roberts S, Bradley A, Hutton P. Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019 Aug;49(11):1761-1775.

Mahoney A, Karatzias T, Hutton P. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of group treatments for adults with symptoms associated with complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders; 243:305-321.

Other references

Brewin CR. (2020). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder: a new diagnosis in ICD-11. British Journal of Psychiatry Advances 26(3), pp. 145 – 152.

Briere J, Elliott DM, Harris K, Cotman A. (1995). Trauma symptom inventory: psychometrics and association with childhood and adult victimization in clinical samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence;10(4):387–401.

Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J and Lu Lassell F (2012). An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depression and Anxiety 29, 709–717.

De Jongh A, Resick PA, Zoellner LA, van Minnen A, Lee CW, Monson CM, Foa EB, Wheeler K, Broeke ET, Feeny N, Rauch SA, Chard KM, Mueser KT, Sloan DM, van der Gaag M, Rothbaum BO, Neuner F, de Roos C, Hehenkamp LM, Rosner R and Bicanic IA (2016) Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depression and Anxiety 33, 359–369.

Harned, M. S., Korslund, K., & Linehan, M. M. (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy with and without the dialectical behavior therapy prolonged exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behavior Research and Therapy, 55, 7–17.

Herman JL. Trauma and recovery: the aftermath of violence – from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books; 1992.

Resick PA, Bovin MJ, Calloway AL, Dick AM, King MW, Mitchell KS, Suvak MK, Wells SY, Stirman SW, Wolf EJ. (2012). A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: implications for DSM-5. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3):241-51.

World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

Photo credits

- Photo by Emiliano Vittoriosi on Unsplash

- Photo by Susan Wilkinson on Unsplash

- Photo by Silas Köhler on Unsplash

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

- Photo by Emily Morter on Unsplash

- Photo by Ruben Ramirez on Unsplash