Self-harm typically begins during adolescence (Cipriano et al., 2017), with 18% of adolescents reporting a minimum of one self-harm incident (Muehlenkamp et al., 2012) due to reasons such as emotion regulation and communicating distress (Taylor et al., 2018).

Although treatment for self-harm exists, adolescents rarely seek help from professionals regarding self-harm (Fortune et al., 2008; Hawton et al., 2012) due to not being aware of available support, feeling that they should cope alone, and fear of being labelled an ‘attention seeker’ (Fortune et al., 2008; Rowe et al., 2014).

These barriers could be addressed via digital mental health interventions (DMHI) such as apps, particularly with the increasing number of adolescents owning mobile phones (Odgers et al., 2018). Although adolescents report a preference for DMHI (Fleming et al., 2019), a limitation of apps is poor engagement (Yeager et al., 2018).

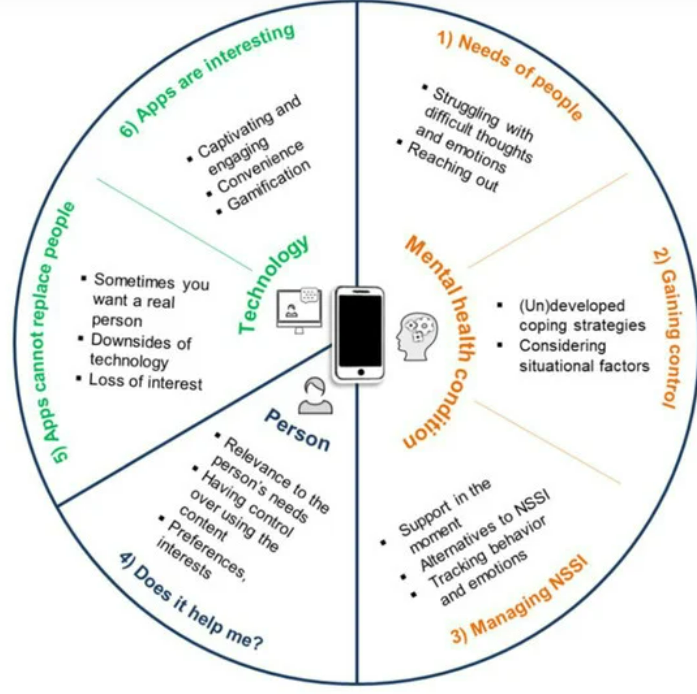

Thus, Čuš et al. (2021) aimed to investigate the needs of adolescents experiencing self-harm to help develop a framework for engaging smartphone interventions for managing self-harm.

Adolescents report having a preference for digital mental health interventions such as apps, but engagement with these interventions are currently poor.

Methods

This qualitative study used purposive sampling to interview 15 female adolescents aged 12-18 years old. Participants were patients recruited by psychiatrists at a Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for engaging in self-harm without suicidal intention for a minimum of five times in the previous year, not within the self-harm subthreshold or as a part of developmental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Interviews were semi-structured, conducted by the first and third author in their therapy office without significant interruptions. Interviewers were not clinically involved with participants before or during interviews. Interviews lasted approximately 40 minutes and were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) recommended six steps. Data analysis was cross-checked by the research team, and one follow-up interview with one participant was conducted as a member checking technique.

Results

Two themes and six subthemes emerged from the data: experiences of self-harm.

Experiences of self-harm

The needs of people who engage in self-harm

- Prior to self-harm, participants experienced negative emotions and used self-harm to self-punish.

- Self-harm helped participants feel stable and free of thoughts and emotions, but some felt guilty afterwards or noticed only temporary relief. Participants were also concerned about receiving invalidating reactions.

Gaining control over self-harm urges

- Some participants reported having no control over self-harm urges, whereas others said they could implement dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) skills, distract themselves, seek help, and/or consider the impact of self-harming on others.

App in context

Managing self-harm

- Self-harm urges lead to an inability to think clearly or read large chunks of text, so participants preferred distraction interventions or help reaching alternative thoughts.

- Support should be self-harm specific during acute states. Participants also wanted support via the app before and after self-harm incidents, and after they have stopped engaging in self-harm.

- Participants wanted to track absence of self-harm, emotional states, and helpfulness of DMHI interventions.

- Those with DBT experiences wanted ‘DBT skills’ built into the app.

- Participants wanted to learn about self-harm alternatives and why they engaged in self-harm, as opposed to learning about self-harm generally.

- Participants wanted to connect with therapists or people with past and/or present self-harm experience via the app, with these interactions being moderated to avoid triggering self-harm between peers.

Does it help me?

- Participants wanted to include their own content and align this with their preferences and interests within the app.

- Participants wanted the choice of engagement and how much time they spend on it.

Apps cannot replace people

- Strategies that required too much effort were seen as a hurdle.

- Some participants did not seem to like that there was not a real person on the other side and viewed speaking to a chatbot as an obstacle.

- Some participants suggested talking to others instead of using technology to manage self-harm.

- Participants struggled to envision relevant content or an appealing format, partly as they were not aware of what can be implemented digitally.

Apps are interesting

- Using an app was perceived as a novelty; convenient and accessible.

- Participants were excited about gamification within the app such as collecting badges, challenges, unlocking new content, and taking care of a character.

- Participants wanted a visually appealing and simplified app, which is user-friendly and categorised, perhaps with videos.

Some participants did not like the lack of human engagement from mental health apps and mentioned the desire to connect with others via an app with interactions being moderated to avoid triggering self-harm between peers.

Conclusions

Overall, this study suggests that digital mental health interventions (such as apps) could be useful for adolescents engaging in self-harm, particularly if the apps consider the participants’ needs, expectations, and suggestions such as including their own content and gamification which may improve engagement. Additionally, those who have seen improvements in their mental wellbeing may engage more with apps compared to those currently experiencing psychological crisis.

This study also suggests that an effective framework for a self-harm management app would be to include evidence-based therapeutic approaches and design strategies, and to develop the app in collaboration with those with lived experience to ensure the app is engaging and relevant.

See below for more information regarding a framework from Čuš et al.’s (2021) study for designing an engaging app for self-harm management.

Strengths and limitations

Although this study has the inherent limitation of authors reaching different data interpretations due to the nature of qualitative research, the authors addressed this through reflexivity, cross-checking data analysis, and member checking, all of which can improve validity and credibility. (Lima et al., 2019; Probst, 2015).

Moreover, whilst all participants were female by chance, which limits the generalisability to all genders, research suggests that females are more likely to engage in self-harm compared to other genders (Bresin et al., 2015). Thus, the sample was representative of the majority of those who engage in self-harm. Still, having male and non-binary participants may have made the study more generalisable, particularly as there may be gender differences.

Another limitation of the study is that interviews were conducted within a therapy office. Although a therapy office may be appropriate as it may prevent interruptions and others hearing the conversation, there is potential for power dynamics to be present (see Edwards & Holland, 2017 for a discussion on this). Thus, the authors could have instead offered a more neutral space for participants, perhaps even asking participants where they would feel most comfortable holding the interview and using the therapy room as a suggestion rather than the only option.

All participants were female, which although is representative of the majority of those who engage in self-harm, means that generalisability to other genders is poor.

Implications for practice

Considering that participants struggled to envision content and format, and the various factors that may influence engagement with apps for self-harm management, it may be useful to design an app in collaboration with mental health professionals, software developers, and those with lived experience (Hollis et al., 2017; Doherty et al., 2010).

Low-effort strategies and techniques from different therapies such as DBT could be used within the app, as suggested by some participants. This would also increase the evidence-base of the app, and should be feasible, as techniques from therapies have previously been successfully implemented into digital formats (Hollis et al., 2017; Schroeder et al., 2018) as seen in, for example, the ‘DBT Coach’ app.

It may be the case that adolescents who do not wish to disengage from self-harm or are in acute mental states might not use an app to manage their urges. Thus, it is important to consider the specific target audience of a self-harm management app, which may help clinicians have a better idea of who to suggest the app to. This is crucial as using the app without it being helpful could lead to negative outcomes.

Although some participants seemed to dislike the fact that there was not a real person on the other side (i.e., some apps use chatbots), if mental health apps become more popular this may improve the psychological wellbeing of some adolescents, put less strain on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and help adolescents manage their self-harm urges both generally and during the typically long waiting lists within CAMHS. This may be particularly useful for those with negative experiences of utilising crisis hotlines, etc., as apps could give them another avenue for managing self-harm.

However, there may be a safeguarding concern with chatbots in the context of high-risk behaviours; Although not mentioned in the study by participants or authors, it may be beneficial from a safeguarding perspective to encourage safety plans, self-referrals to crisis teams, etc. Additionally, these types of apps are arguably a grey area regarding ethics as they capture information about a person’s desire to self-harm or recent self-harm behaviour; Perhaps future research should consider how this information can be passed on to clinicians and/or emergency services to help safeguard those using these apps.

Lastly, consideration regarding the age range for those who may benefit from this type of app is needed. Future research could investigate this and even consider what a similar app for children as well as adults could also look like.

Future research should consider collaboration with mental health professionals and those with lived experience on the development of an app to help adolescents manage self-harm urges.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Čuš, A., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Ohmann, S., Plener, P. L., & Akkaya-Kalayci, T. (2021). “Smartphone Apps Are Cool, But Do They Help Me?”: A Qualitative Interview Study of Adolescents’ Perspectives on Using Smartphone Interventions to Manage Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(6), 3289.

Other references

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Bresin, K., & Schoenleber, M. (2015). Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 38, 55-64.

Cipriano, A., Cella, S., & Cotrufo, P. (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1946.

Doherty, G., Coyle, D., & Matthews, M. (2010). Design and evaluation guidelines for mental health technologies. Interacting with computers, 22(4), 243-252.

Edwards, R., & Holland, J. (2013). What is qualitative interviewing?. A&C Black.

Fleming, T., Merry, S., Stasiak, K., Hopkins, S., Patolo, T., Ruru, S., … & Goodyear-Smith, F. (2019). The importance of user segmentation for designing digital therapy for adolescent mental health: findings from scoping processes. JMIR mental health, 6(5), e12656.

Fortune, S., Sinclair, J., & Hawton, K. (2008). Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: a descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC public health, 8(1), 1-13.

Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet, 379(9834), 2373-2382.

Hollis, C., Falconer, C. J., Martin, J. L., Whittington, C., Stockton, S., Glazebrook, C., & Davies, E. B. (2017). Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems–a systematic and meta‐review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 474-503.

Lima, R. S., & Gonçalves, M. F. C. (2019). Pesquisa qualitativa de sucesso: Um guia prático para iniciantes. Rev. enferm. UFPE on line, 1-2.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 6(1), 1-9.

Odgers, C. (2018). Smartphones are bad for some teens, not all. Nature, 554(7693), 432-434. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-02109-8

Probst, B. (2015). The eye regards itself: Benefits and challenges of reflexivity in qualitative social work research. Social Work Research, 39(1), 37-48.

Rowe, S. L., French, R. S., Henderson, C., Ougrin, D., Slade, M., & Moran, P. (2014). Help-seeking behaviour and adolescent self-harm: a systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(12), 1083-1095.

Schroeder, J., Wilkes, C., Rowan, K., Toledo, A., Paradiso, A., Czerwinski, M., … & Linehan, M. M. (2018, April). Pocket skills: A conversational mobile web app to support dialectical behavioral therapy. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15).

Taylor, P. J., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., & Dickson, J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of affective disorders, 227, 759-769.

Yeager, C. M., & Benight, C. C. (2018). If we build it, will they come? Issues of engagement with digital health interventions for trauma recovery. Mhealth, 4.

Photo credits

- Photo by Rami Al-zayat on Unsplash

- Photo by Aedrian on Unsplash

- Photo by Kate Kalvach on Unsplash

- Photo by Dainis Graveris on Unsplash

- Photo by Brooke Cagle on Unsplash