Living with a mental health condition is an extremely subjective experience, and what is considered effective by psychiatrists may not necessarily be as effective in a patient’s opinion.

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness, is characterised by extreme changes in mood, energy level and the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Affecting more than one percent of the world’s whole population, it can have a devastating impact on one’s daily life by causing a significant amount of distress and suffering.

The first-line intervention for bipolar disorder recommended in the NICE guideline is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), a psychological therapy targeting unhelpful thoughts, beliefs and behaviours underlying a mental health condition. Despite the well-established effectiveness of CBT for symptom reduction, it is debated whether it truly eases an individual’s suffering.

Adopting a recovery approach in treating bipolar disorder may be the answer. Contrary to the traditional symptom-based medical approach, a recovery approach promotes person-centred support to enable individuals to live a purposeful and satisfying life. Many believe this is why understanding individual sources of distress should come before tackling the overarching symptoms of bipolar disorder.

Previous studies have shown that distress is prevalent among people with bipolar disorder. The distress can originate from side effects of the medication, the collapse of social relationships and a sense of losing control. While many studies have touched upon the distressing factors for people with bipolar disorder, none of them have been specifically designed to explore distress in bipolar disorder. Therefore, it is important to integrate the existing evidence and extract what bipolar disorder patients experience as distressing.

In supporting people with bipolar disorder, should we be aiming to reduce symptoms or alleviate suffering? Is there a difference between these two objectives?

Methods

Terms relating to bipolar disorder were used to search for relevant articles on scientific databases (Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO and ASSIA). The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P) statement guidelines.

To be included in the review, studies had to have a qualitative design, be written in English, include first-person accounts of distress by individuals with a bipolar disorder diagnosis from one-to-one interviews, and be based on the theme of distress. Studies that were excluded from the review were those that had a quantitative or mixed methods methodology, included individuals with an organic cause for their bipolar disorder experiences, those that compared bipolar group qualitative data with other psychiatric diagnosis, and studies that focused on a specific intervention.

5,201 records were initially found, but this was reduced to 1,369 articles after duplicated articles were removed. Reference lists from these articles were screened to identify further relevant papers. This search strategy was re-run at a later stage (July 2018) to account for any recent publications.

Findings from these qualitative studies were synthesised, a method known as ‘thematic synthesis’. This involved coding the data, line by line, to generate descriptive codes. These codes were grouped to allow for comparisons to be made across papers so overarching descriptive themes could be developed. Using these descriptive themes, higher-level analytical themes were created where further refinement of the data took place to ensure thematic synthesis was addressing the research question for this review.

Overall, 24 studies met the criteria and were included in this review.

Results

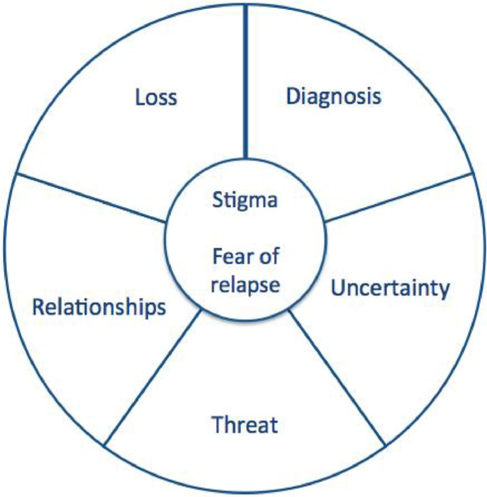

Five major ‘themes’ contributed to distress among individuals with bipolar disorder

1. Diagnosis

Patients found it difficult to accept a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and were discouraged by the negative reports of others who had the same diagnosis. Taking medication was unpleasant and sometimes ineffective for some. Others found themselves relying too heavily on medication.

2. Loss

Most people reported experiencing loss of control over their lives. This was due to their inability to manage their moods and difficulty maintaining their jobs and friendships.

3. Uncertainty

Many people also described often feeling uncertainty and confusion because before having a diagnosis, they did not understand the symptoms they were experiencing. Even after getting diagnosed they often felt confused because they could not tell when they were under the influence of medication, and they felt they were not getting enough information from mental health professionals. Uncertainty about whether or not to take medication or how to balance mental health and other responsibilities led to distress and worrying about the future.

4. Threat

The experience of bipolar disorder left many people feeling constantly under threat; mood changes were abrupt and extreme and often dangerous. This sometimes resulted in embarrassment, regret, and feelings of inadequacy.

5. Relationships

This involved loss of friends, partners, and even children. Many also felt misunderstood and neglected by their healthcare professionals.

Two cross-cutting sub-themes

Linking these five themes were stigma and fear of relapse. Patients felt labelled and treated differently because of their diagnosis, and expressed a constant fear of minor symptoms escalating into depressive or manic episodes.

Figure 1. A model of the themes reported to cause distress.

Conclusions

This paper was the first to explore what people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder experience as distressing.

Among the five emerging key themes, “loss” (relating to loss of control, social connection, identity) was the largest theme. A central feature of this loss concerns the unattainability of goals (Kelly et al., 2013), which may manifest in a variety of other life contexts, such as job loss or even injury. The sense that one may have to change patterns of living and goals creates a sense of discontinuity and distress.

Stigma, a sense of social isolation may emerge and individuals “seeing themselves as the disorder” are experiences of distress that transcend the clear boundaries of symptom categories in bipolar disorder.

Interestingly, these interpersonal and intrapersonal themes of distress seem to occur across mental health conditions, as they have also been described by individuals with first episode psychosis (Griffiths et al., 2018).

People with bipolar disorder report finding diagnosis, loss, uncertainty, threat, relationships, stigma and fear of relapse as distressing experiences.

Strengths and limitations

As no literature has previously explored distress among individuals with bipolar disorder, this qualitative meta-synthesis provides valuable insight into experiences which seem to be largely unaddressed by modern psychological treatment. Importantly, its conclusions are drawn from a rigorous methodological design. The thematic synthesis of methodologically strong qualitative studies allows for greater combination of information from multiple qualitative approaches.

However, a major limitation lies in the data extraction and coding being conducted by one author, even though discussions took place in later stages. This not only risks biasing the interpretations made, it also lacks valuable insight that could emerge in a more collaborative, reflective process in the development of themes relating to distress. This absence of reflexivity, which is central to qualitative research (Braun and Clarke, 2013), was also identified by the authors as a limitation in included studies. Authors’ and participants’ relationships, which are meaningful additions to interviews, had not been discussed.

Finally, the exclusion of studies not conducted in English, and the subsequent inclusion of studies conducted in predominantly high-income western countries, substantially limits the generalisability of findings to other contexts. Authors need to be explicit, because they risk assuming a universality of concepts, when they were in fact described in a specific, limited context.

Only one author extracted and coded data for this review, which is likely to have limited the amount of insight that could have emerged, compared with a more collaborative and reflective process involving two or more researchers.

Implications for practice

Overall, this meta-synthesis sheds light on the limitation of current psychological therapies in effectively targeting the experiences that people with bipolar disorder report as most distressing. The good news: the overarching themes influencing distress appeared relatively consistent across studies reviewed, and are known to be experienced in other mental health conditions, indicating that they may be promising directions for the field of mental illness treatment as a whole. Concerning the noteworthy theme of loss of control, one promising new direction of treatment would be to “disentangle” sources of threat and anxiety (Jones et al., 2013), rather than “change” of symptoms, which seems to be the current model of psychological therapies.

Finally, this study has highlighted something that is easily lost in a world of standardised measurements and treatments: the importance of practicing therapy focused on the individual needs of each patient. One way to achieve this, as suggested by the authors, would be to use interview techniques to explore what each individual finds distressing, and use it as a personalised goal of therapy.

When supporting people with bipolar disorder, have you considered using interview techniques to explore what each individual finds distressing, and use it as a personalised goal of therapy?

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Emily Roxburgh, Amal Althobaiti, Amy Lewins (@AmyLewins1), Eirini Melegkovits (@melengovits), Natasha Melunsky, Idongesit Eseneyen (@IdongesitEsene2), Lidushi Nagularaj (@Lidushi_97), Siddhi Shah, Nura Bejani and Peiyao Tang (@TangPeiyao).

Conflicts of interest

None.

UCL MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a group of students on the Clinical Mental Health Sciences MSc at University College London. A full list of blogs by UCL MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Warwick H, Mansell W, Porter C, Tai S. (2019) ‘What People Diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Experience as Distressing’: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research. Journal of Affective Disorders, 248, 108-130.

Other references

Jones, S., McGrath, E., Hampshire, K., Owen, R., Riste, L., Roberts, C., Davies, L., Mayes, D., (2013). A randomised controlled trial of time limited CBT informed psychological therapy for anxiety in bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry 13 (1), 54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-54.

Griffiths, R., Mansell, W., Edge, D., Tai, S., (2018). Sources of distress in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318790544.

Photo credits

- Photo by Caleb George on Unsplash

- Photo by Mike Enerio on Unsplash

- Photo by Taylor Smith on Unsplash

- Photo by Filip Bunkens on Unsplash