For anyone working with children or young people, it will come as no surprise to discover that the prevalence of poor mental health is growing, with most teachers able to think of at least one student struggling with low mood. Recent UK data suggests that 9% of 11-16 year olds and 15% of 17-19 years have a diagnosable disorder such as anxiety or depression (Vizard et al., 2018), however many argue that this is just the tip of the iceberg, with there being many more young people just below the threshold for diagnosis (Bertha & Balazs, 2013).

It is important that we intervene early to address emerging poor mental health as studies repeatedly show that emotional disorders during childhood and adolescence can lead to consequences such as long term poor mental and physical health, low educational achievement, unemployment and increased risk of substance abuse and criminal behaviour (Clayborne, Varin, & Colman, 2018; Essau, Lewinsohn, Olaya, & Seeley, 2014; Keenan- Miller, Hammen, & Brennan, 2007).

The evidence suggests that early intervention can prevent this downward slide (Bockting, Hollon, Jarrett, Kuyken, & Dobson, 2015; Neufeld, Dunn, Jones, Croudace, & Goodyer, 2017) but it also reveals that most young people are failing to access it (Children & Young People’s Mental Health & Wellbeing Taskforce, 2015; Merikangas et al., 2011). There are many possible reasons for this including:

- Lack of knowledge about mental health leading to stigma and failure to seek help (Langer et al., 2015; Plaistow et al., 2013; Reardon et al., 2017).

- The failure of primary health care professionals such as GPs to make the necessary referrals to specialist services (O’Brien, Harvey, Howse, Reardon, & Creswell, 2016).

- The threshold for child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) being too high (Department of Health & Department for Education, 2017; Frith, 2016), leading to long waiting lists and failure to meet the threshold for treatment (Crenna- Jennings & Hutchinson, 2018).

Schools have the potential to make a real difference in terms of all three of these barriers. Not only do teachers have the advantage of already having built good relationships with young people, their experience makes them well placed to identify young people struggling with emotion and mood (Patel et al., 2018; Public Health England, 2015).

The green paper ‘Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision’ (Department of Health & Department for Education, 2017) is the start of government recognising the important role schools can play in addressing mental health concerns. The paper details how money and training have been made available for nurse-led mental health support teams to provide evidence-based interventions in a school setting (Department of Health & Department for Education, 2017).

A recent review by Gee et al (2020) examines and evaluates data from randomised controlled trials of targeted school-based interventions for treating adolescents who are already showing signs of depression and anxiety. In order to establish the quality of the evidence presented, the review also examines the methods using the ‘preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses’ (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2009) to ensure the evidence is valid and applicable.

Schools have the potential to make a real difference as teachers have the advantage of already having built good relationships with young people and their experience makes them well placed to identify young people struggling with emotion and mood.

Methods

Eight electronic databases and reference lists were searched in order to identify randomised controlled trials that met the criteria of:

- A school-based intervention

- Use of a manual

- A treatment, not a preventative measure

- Targeted young people (ages 10-19) who were already displaying signs of anxiety and depression

- Aimed at reducing the symptoms of emotional disorders.

The original research was required to meet set standards (Cuijpers et al., 2010) including those used to measure the impact of mental health interventions (Moncrieff, Churchill, Colin Drummond, and McGuire, 2001), this included the use of trained therapists, monitoring for accurate use of the manual, and anonymised data collection.

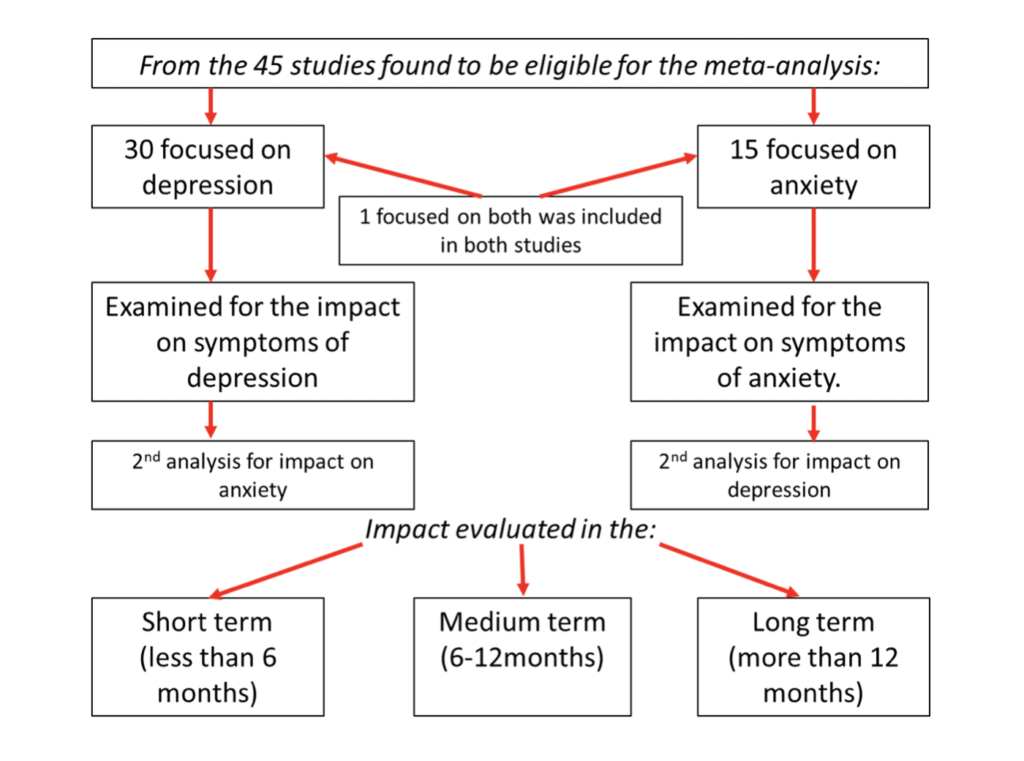

From using this process 45 studies were found to be eligible for the meta-analysis, 30 focused on depression, 15 on anxiety and 1 on depression and anxiety.

Results

Anxiety focused interventions

Group interventions targeting anxiety were more effective than those for depression. It is believed that this is because the use of a group normalised anxiety whilst providing peer support and modelling in a social environment (Wergeland et al., 2014).

Anxiety interventions delivered outside of school were more effective than those delivered internally (Reynolds et al., 2012), potentially because school-based interventions were unable to use the exposure-based strategies available to external groups (Bernstein, 2010; Drmic, Aljunied, & Reaven, 2017; Masia-Warner et al., 2016).

Depression focused interventions

One to one sessions appear to have been more effective than group interventions (Wergeland et al., 2014), but the original researchers highlight that numbers involved were low so this should be viewed with caution. Surprisingly, the study also revealed that parental involvement had little impact on the symptoms of depression, possibly due to practical difficulties, such as resources and time, surrounding this (Drmic et al., 2017; Melnyk, Kelly, & Lusk, 2014). This is significant as other research and guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) encourage parental involvement (Dardas, van de Water, & Simmons, 2018; NICE, 2005).

Effectiveness of interventions delivered by school staff

From examining data across the 45 studies, researchers established that school-based interventions delivered by specialists were more effective than a do nothing approach.

Unfortunately, when interventions were delivered by school staff, there was no significant impact on either depression or anxiety symptoms; this is believed to be due to failure to adhere fully to the programme or manual. This is a crucial finding as in order for school based interventions to be sustainable, school staff need to able to take part in delivery, consequentially this is something that needs further examination (Herzig-Anderson, Colognori, Fox, Stewart, & Masia-Warner, 2012).

Long-term impact

Disappointingly the research showed that the long-term impact of all school-based interventions was limited with only a slight impact on depression symptoms for up to 6 months after the intervention, and no significant long-term effects on anxiety. This suggests that additional strategies are needed to prolong the efficacy of such interventions once they have come to an end.

School-based interventions delivered by specialists worked better than those delivered by school staff.

Conclusions

This review of 45 studies of school-based interventions revealed that, dependent on a number of factors, they can have a positive impact on both depression and anxiety, but that the long-term benefits have yet to be demonstrated.

As the government and local authorities begin to implement the Green Paper by introducing Mental Health Support Teams into schools, it is ever more vital that we understand the lessons of previous interventions in order to create effective and sustainable treatment programmes to target the growing number of young people with emerging emotional disorders.

School-based interventions can have a positive impact on teen depression and anxiety, but the long-term benefits are still uncertain.

Strengths and limitations

- The results are potentially biased due to not being able to obtain missing data for all eligible studies.

- It was not possible to adjust data from cluster randomised trials due to missing data, meaning results may be skewed.

- The analysis of subgroups is not directly comparable due to them not being randomised, therefore results should be treated with caution.

Implications for practice

There is a need for more high quality trials of school-based interventions for anxiety and depression, which also need to incorporate longer term follow-ups.

There is an urgent need for research into psychological interventions delivered in post 16 years old education and specialist schools including those for expelled students.

Research needs to look at the potential costs and adverse effects of school-based psychological interventions.

There is an urgent need for more high quality trials of school-based interventions.

Conflicts of interest

None reported.

Links

Primary paper

Gee, B., Reynolds, S., Carroll, B., Orchard, F., Clarke, T., Martin, D., Wilson, J. and Pass, L. (2020) Practitioner Review: Effectiveness of indicated school‐based interventions for adolescent depression and anxiety – a meta‐analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13209

There’s a video abstract featuring first author Brioney Gee on @TheJCPP Twitter.

Other references

Bernstein, E. R. (2010). Transportability of evidence-based anxiety interventions to a school setting: Evaluation of a modularized approach to intervention. University of Wisconsin- Madison.

Bertha, E. A., & Balazs, J. (2013). Subthreshold depression in adolescence: A systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 22, 589–603.

Bockting, C. L., Hollon, S. D., Jarrett, R. B., Kuyken, W., & Dobson, K. (2015). Clinical Psychology Review: A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: The contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 16–26.

Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Taskforce (2015). Future in mind: Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. London.

Clayborne, Z. M., Varin, M., & Colman, I. (2018). Adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58, 72–79.

Crenna-Jennings, W., & Hutchinson, J. (2018). Access to children and young people’s mental health services: 2018. Available from: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/32275/.

Cuijpers, P., Van Straten, A., Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D., & Andersson, G. (2010). The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: A meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychological Medicine, 40, 211–223.

Essau, C. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., Olaya, B., & Seeley, J. R. (2014). Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. Journal of Affective Disorders, 163, 125–132.

Melnyk, B. M., Kelly, S., & Lusk, P. (2014). Outcomes and feasibility of a manualized cognitive-behavioral skills building intervention: Group COPE for depressed and anxious adolescents in school settings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 27, 3–13.

Department of Health & Department for Education (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. Cm 9523.

Drmic, I. E., Aljunied, M., & Reaven, J. (2017). Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary treatment outcomes in a school-based CBT Intervention Program for Adolescents with ASD and Anxiety in Singapore. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3909–3929.

Frith, E. (2016). Children and young people’s mental health: State of the Nation. London: Education Policy Institute. Available from: https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-House

Herzig-Anderson, K., Colognori, D., Fox, J., Stewart, C. E., & Masia-Warner, C. (2012). School-based anxiety treatments for children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21, 655–668.

Keenan-Miller, D., Hammen, C. L., & Brennan, P. A. (2007). Health outcomes related to early adolescent depression. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 256–262.

Langer, D. A., Wood, J. J., Wood, P. A., Garland, A. F., Landsverk, J., & Hough, R. L. (2015). Mental health service use in schools and non-school-based outpatient settings: Comparing predictors of service use. School Mental Health, 7, 161–173.

Masia-Warner, C., Colognori, D., Brice, C., Herzig, K., Mufson, L., Lynch, C., . . . & Klein, R. G. (2016). Can school counselors deliver cognitive-behavioral treatment for social anxiety effectively? A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 11, 1229–1238.

Melnyk, B. M., Kelly, S., & Lusk, P. (2014). Outcomes and feasibility of a manualized cognitive-behavioral skills building intervention: Group COPE for depressed and anxious adolescents in school settings. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 27, 3–13.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., . . . & Olfson, M. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the national comorbidity survey Adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 32–45.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., Antes, G., . . . & Tugwell, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6, e1000097.

Moncrieff, J., Churchill, R., Colin Drummond, D., & McGuire, H. (2001). Development of a quality assessment instrument for trials of treatments for depression and neurosis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 10, 126–133.

Neufeld, S. A. S., Dunn, V. J., Jones, P. B., Croudace, T. J., & Goodyer, I. M. (2017). Reduction in adolescent depression after contact with mental health services: A longitudinal cohort study in the UK. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4, 120–127.

NICE (2005). Depression in children and young people: Identification and management. London: British Psychological Society, Royal College of Psychiatrists.

O’Brien, D., Harvey, K., Howse, J., Reardon, T., & Creswell, C. (2016). Barriers to managing child and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review of primary care practitioners’ perceptions. British Journal of General Practice, 66, e693–e707.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., . . . & Un€ Utzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet, 392, 1553–1598.

Plaistow, J., Masson, K., Koch, D., Wilson, J., Stark, R. M., Jones, P. B., & Lennox, B. R. (2013). Young people’s views of UK mental health services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 8, 12–23.

Public Health England (2015). Promoting children and young people’s emotional health and wellbeing. A whole school and college approach. PHE publications gateway number: 2014825. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_Vizard

Reardon, T., Harvey, K., Baranowska, M., O’Brien, D., Smith, L., & Creswell, C. (2017). What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 623–647.

Reynolds, S., Wilson, C., Austin, J., & Hooper, L. (2012). Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 251–262.

Vizard, T., Pearce, N., Davis, J., Sadler, K., Ford, T., Goodman, A., & McManus, S. (2018). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017: Emotional disorders. NHS Digital. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017.

Wergeland, G. J. H., Fjermestad, K. W., Marin, C. E., Haugland, B. S. M., Bjaastad, J. F., Oeding, K., . . . Heiervang, E. R. (2014). An effectiveness study of individual vs. group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 1–12.

Photo credits

- Photo by You X Ventures on Unsplash

- Photo by Bill on Unsplash

Some good points. However, government have been discussing having counsellors since 2015. All dependent on whether a secondary school wants to implement it. Studies conducted on PSHE in 2015 also found that the knowledge and delivery of it was poor in two thirds of secondary schools in the UK. As a nation, we keep focusing on the problem. We are talking about adolescents here. Going through one of the most difficult development stages of a human being spanning up to 25. Going through self identity crisis issues possibly. Told what to do. Stuck in classes of 30. Told what to learn. Its not right. They need to have autonomy in the school and classroom. We need to focus on autonomy, self efficacy and wellbeing. Most mental illness begin during adolescency. We need to be proactive as a society, as practitioners to make the journey of adolescency worth living.

As for CAMHS, I’ve noticed that some young people have had to wait till they end up in hospital taking an overdose before they get seen. In addition they are conducting CBT with practitioners that are not qualified. Theyve not put in the resources required for such a large organisation. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy both one to one and group work has shown improvement in studies. Perhaps theres a way to begin replicating this in secondary schools, to do group work. Studies have also shown that any intervention programs has to be on going. If you think about it, it has to. An adolescent brain is rewiring itself. Any program needs to go all the way through school, every week. Its taken decades just to get PSHE on the statutory curriculum. Sweden are heading in the right direction giving more autonomy to their students by being able to pick their own subjects. Now no longer have to do the statutory subjects unless they want to.