The relationship between work and mental health is becoming a priority both for policy makers and employers. We know that when our workplaces support our ability to thrive, the identity, income and purpose that work can bring can be good for our mental health. Equally, much has been written about the impact of toxic working environments in terms of the impact of bullying, harassment and discrimination at work.

To date, much of the focus of debate has been on the cost of lost productivity due to mental ill health; of the order of £26 billion per year. According to recent research using Labour Force Survey data (Mental Health Foundation, 2016), the value added by people in the UK working with mental health problems is as many as nine time greater at £226 billion per year, or 12.1% of total GDP (gross domestic produce).

We need to know more about how to protect and improve mental health as a workplace asset. Prevention is a major focus of interest in workplace mental health going forward, but the evidence for interventions are in their infancy, a topic covered by Laurence Palfreyman in a Mental Elf blog in June 2014.

A thriving work environment can bring a sense of identity and purpose for individuals, as well as the income they need to survive.

Methods

The authors adopted a robust search strategy for English language reviews using MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Embase and the Cochrane Collaboration databases. The review included only papers that considered common mental health problems, specifically depression, anxiety and/or work related stress, in which the role of work or work related risk factors were considered.

The quality of selected reviews was assessed using the AMSTAR checklist, with the quality of reviews presented throughout the findings, emphasising evidence that came from reviews with moderate or high quality scores.

Results

A wealth of evidence supporting a relationship between work and common mental health problems.

From an initial search screen of 7,542 studies, 40 full texts were screened and 37 reviews were found to meet the inclusion criteria. Of these, seven reviews scored as being of at least moderate quality on AMSTAR. These seven included analysed 213 primary research studies, with evidence of only minimal overlap between studies included. Twelve work related risk factors were identified amongst the included reviews. These factors were assessed in relation to a number of existing models for framing stress and distress in the workplace.

Summary of Evidence Relating to Established Models of Workplace Mental Health

Job Demand-Control-Support (JDCS) Model

Asserts that jobs where low control over factors such as decision making are combined with high demands, such as increased workload/time pressure created a ‘high strain’ situation and can be associated with the highest risk of illness and reduced wellbeing.

Some evidence suggests that good social support in the workplace may moderate these adverse effects (Sanne, Mykletun, Dahl et al, 2005).

Good evidence for a relationship between poorer employee mental health and high job demand, low job control and low social support.

- Stansfield and Candy (2006) found that the risk of an employee developing a common mental health problem could be predicted by low job control, high psychological demands and low occupational social support.

Theorell et al (2015), Nieuwenhuijsen et al (2010) and Netterstrom et al (2008) found a connection between these factors and the development of depression, and the occurrence of stress related disorders.

The review found strong evidence for a relationship between high job demand, low job control, low social support and poor employee mental health.

Effort Reward Imbalance (ERI) Model

Based on an employee’s perception of the balance between the effort they put into their work and the reward (financial and otherwise) they received for this. It proposes that the most stressful situations are those where the reward is lower than the effort (Siergrist, Stark, Chadola et al, 2004).

Three reviews of moderate quality explored the impact of high ERI on the mental health of workers.

- Stansfield and Candy (2006) concluded that High ERI is associated with increased risk of common mental disorders; based on comparison of two longitudinal studies with over 12,000 subjects.

- Nieuwenhuijsen et al (2010) found a significant association between high ERI and stress related disorders on the workplace.

Theorell et al (2015) identified some limited evidence for a relationship between high ERI and increased depression symptoms.

Unsurprisingly, jobs that had high effort and low reward were associated with an increased risk of common mental disorders.

Organisational Justice Model

The organisational justice model (Elovainio et al, 2002) refers to the fairness of rules and social norms within companies in three dimensions:

- The distribution of resources and benefits (Distributive Justice)

- The methods and processes governing that distribution (Procedural Justice)

- Interpersonal relationships (Interactional Justice), which includes two elements:

- The level of dignity and respect received from management (Relational Justice)

- The presence or absence of adequate information from management about workplace procedures (Informational Justice)

Two moderate quality and one low quality review explored this relationship, with most studies focusing on relational and procedural justice.

- Nieuwenhuijsen et al (2010) found that low relational justice and low procedural justice were associated with increased risk of stress related disorders

- Theorell et al (2015) found more limited evidence for the impact on either procedural or relational justice on depression symptoms

- One lower quality review (Ndjaboue et al, 2012) found that low procedural justice and low relational justice were associated with increased likelihood of mental health problems amongst employees

Low relational and procedural justice were associated with an increased risk of stress.

Additional Factors Considered

Organisational Change and Job Security

Organisational change is now a given in working life in most fields. Bamberger et al (2012) reviewed 17 studies assessing various forms of organisational change. Eleven of these studies observed a negative relationship between organisational change and mental health.

There is some evidence for a relationship between job insecurity and poor mental health with one review of three studies reporting a moderate odds ratio between the factors (Stansfield and Candy, 2006). In contrast Theorell et al (2015) concluded that there was only limited evidence for an association between job insecurity and depression symptoms.

Employment Status and Atypical Working Hours

Virtanen et al (2005) reported that temporary employees have higher psychological morbidity compared with permanent employees. Harvey et al point out though that the definition of psychological morbidity is not clear, and also reflect that many people with mental health problems are more likely to be offered temporary contracts compared with ‘healthy individuals’.

In terms of working hours, the review points mainly to the impact of long working hours. Theorell et al (2015) show limited evidence of an association between a ‘long working week’ and depressive symptoms.

Workplace Conflict and Bullying

The authors identified five meta-analyses that examined the impact of workplace conflict and bullying on the development of mental disorders.

Theorell et al (2015) showed moderately strong evidence for an association between workplace bullying and increased depression symptoms. In the same review, there was only limited evidence for an impact of workplace conflict with superiors and co-workers on depression symptoms. Verkuil et al (2015) showed that workplace bullying increased symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress related psychological symptoms, although there were some questions raised about the quality of this review.

Role stress

The two most researched aspects of role stress in relation to mental health are:

- Role ambiguity: where an employee lacks information about their role’s responsibilities and objectives

- Role conflict: when there are two or more opposing expectations about the employee’s role.

One meta-analysis of 32 studies (Schmidt et al, 2014) analysed by the authors found that role conflict and role ambiguity were related to an increase in depressive symptoms.

Lack of clarity about work role was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

A new model for linking and understanding potential risk factors in the workplace.

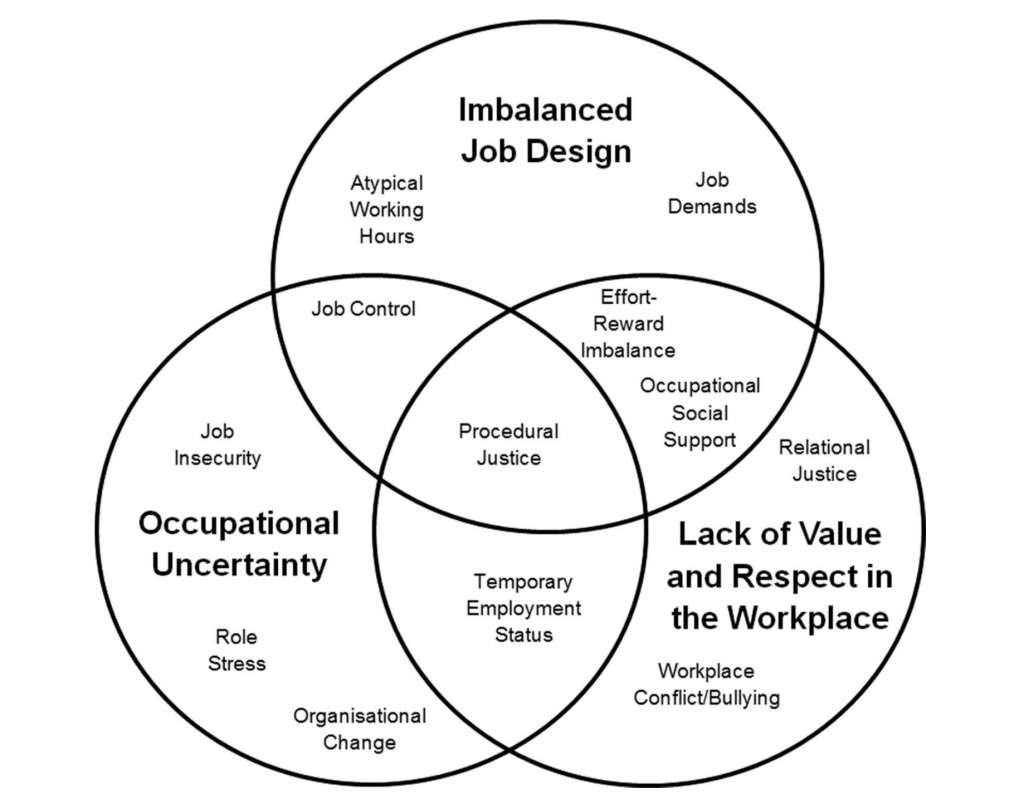

Based on the findings of the review, the authors present a new, unifying model of the psychosocial workplace with three overlapping clusters of workplace risk factors; imbalanced job design, occupational uncertainty and a lack of value and respect within the workplace.

The unifying model of workplace risk factors.

Subject to the limitations discussed below and identified by the team, the review suggests four conclusions regarding the relationship between work and common mental disorders:

- There is consistent evidence for an association between some workplace situations and common mental health problems, though methodological concerns mean casual inferences must be made with caution

- There are a further range of emerging work factors that appear to increase the risk of common mental health problems, but where further research is needed

- There is no magic bullet or single source of toxicity, but there are new overlaps between factors emerging

- The interaction between individual and organisational factors is complicated, and there is a need for better methodologies to assess the direction of causality.

Strengths and limitations

A strong meta-review, with some reservations about methodological weaknesses in some of the included studies.

It is perhaps a surprise that efforts to bring together themes relating to risk factors for common mental health problems in the workplace has not been done before. The authors appear to have produced a robust, valuable review that uses a strong methodology, and errs on the side of caution in both inclusion criteria and in anticipating potential concerns in reporting and limitations of the study.

As the team point out, meta-review methodologies allow coverage of a wide range of themes, and this has certainly been the case here, drawing together evidence on twelve separate potential risk factors. The down side, as identified, is that the time taken for reviews to be published can lead to primary research of potential conclusion altering relevance not being included in a ‘definitive’ meta-review.

There are key areas in the model proposed where the pace of change in workplace contexts is such that there are gaps which could and should be filled. Most notably these could include studies relating to insecure employment in zero-hours contracts or other precarious employment.

There are some key limitations in the body of primary research that are picked up by the authors and are worthy of further consideration.

Firstly the authors point to the challenges of using self-reporting questionnaires to source data from employees about their experiences both of distress, and of circumstances relating to their employment. It is possible that a wide range of personal beliefs, attitudes and individual factors will influence respondents’ ability to accurately comment on their experience.

The authors also point to the possibility of reverse causation being a factor:

Reverse causation is also a possibility via early life mental illness increasing the risk of an individual finding themselves working in a suboptimal environment.

People with life history of mental health problems are still subject to profound inequalities, including in accessing and thriving in the labour market. If we are to address the very real challenges of ensuring work environments support people with declared and undeclared lived experience, we must see both sides of this equation; understanding not just how working life affects the development of mental health problems, but also how these same competing pressures interact with existing mental health concerns and personal factors such as experience of trauma. Research looking at mental health and the workplace must pay due regard to this complexity, and we must seek methodologies that enable robustness and replicability, without becoming too in-vitro and artificial.

Future research efforts need to reflect the complexity of work life with a mental health problem.

Implications for practice

We have much more to do to understand the hazards of modern employment to mental health, so that we can prevent distress early.

Samuel Harvey and his team present a meta-review seeking to understand the relationship and interaction between risk factors for common mental health problems in the workplace. With a strong design, and new model proposed for understanding the interplay between factors, this paper is a useful addition to the evidence that is accessible and usable by practitioners, and HR professionals. It presents fertile ground for the development and testing of interventions in this field.

There is an abiding narrative in public policy today that work is good for health, and mental health in particular. There is ample evidence to support the fact that ‘good’ work can support good health, but far less focus on the hazards to mental health of poor working conditions. This review helps to develop our understanding of psychological hazards in the workplace. In practice this should help ensure that we have due regard for obligations to staff under health and safety legislation, and to ensure that staff who experience distress or mental health problems can join the workforce and thrive in the workplace.

Within these results lie a range of potential interventions that researchers should seek to develop and evidence for preventing mental health problems developing. The three overlapping clusters of workplace risk factors: imbalanced job design, occupational uncertainty and a lack of value and respect within the workplace provide a framework for action on which all stakeholders could be building, innovating and evidencing.

We need to recognise that people are working in rapidly changing environments where the risk of psychological injury is high. We need to recognise that the riskiest jobs; those with the most demand and the least control, the least reward per effort, and where the organisational justice is negligible are those often occupied by people with mental health problems. This review doesn’t include any evidence about precarious employment, working multiple jobs, or the effect of compulsion into any employment arising from social security policy, a gap which we need to understand.

We need to stop seeing mental health at work as something which is ‘reasonably adjusted’ for those with mental health problems to an asset we all have and which is at major risk in every modern workplace. Then, when we have come to terms with the need to manage risk, we need to move beyond risk to promotion, moving beyond prevention of illness to improving mental capital.

This review started with a question. Can work make you mentally ill? The answer is yes, it seems it can. We have much more to do to understand the hazards, alongside the benefits of modern employment to mental health.

We need to move beyond risk to promotion, moving beyond prevention of illness to improving mental capital.

Conflicts of interest

Chris O’Sullivan works for the Mental Health Foundation, a national mental health charity focused on prevention in mental health, with an interest in promoting mental health at work.

Links

Primary paper

Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, et al (2017) Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med Published Online First: 20 January 2017. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104015 [Abstract]

Other references

Bamberger SG, Vinding AL, Larsen A, et al (2012). Impact of organisational change on mental health: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2012;69:592–8.

Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Vahtera J. (2002) Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health 2002;92:105–8.

Mental Health Foundation (2016) Added Value: Mental Health as a Workplace Asset; London; 2016

Ndjaboue R, Brisson C, Vezina M (2012) Organisational justice and mental health: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med 2012;69:694–700.

Netterstrom B, Conrad N, Bech P, et al (2008) The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev 2008;30:118–32.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bruinvels D, Frings-Dresen M (2010) Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup Med (Oxford) 2010;60:277–86.

Sanne B, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, et al (2005) Testing the Job Demand-Control-Support model with anxiety and depression as outcomes: the Hordaland Health Study. Occup Med (Lond) 2005;55:463–73

Schmidt S, Roesler U, Kusserow T, et al (2014) Uncertainty in the workplace: examining role ambiguity and role conflict, and their link to depression—a meta-analysis. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2014;23:91–106.

Siergrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, et al (2004) The measurement of effort-reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1483–99.

Stansfeld S, Candy B (2006) Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review [PDF]. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:443–62.

Theorell T, Hammarstrom A, Aronsson G, et al (2015) A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015;15:738.

Verkuil B, Atasayi S, Molendijk ML (2015) Workplace bullying and mental health: a meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS ONE 2015;10: e0135225.

Virtanen M, Kivimaki M, Joensuu M, et al (2005) Temporary employment and health: a review. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:610–22.

Photo credits

[…] Work can make you mentally ill, but we still have a lot to learn about the links between employment … […]

[…] “Work can make you mentally ill, but we still have a lot to learn about the links between employment and mental health” (The Mental Elf) […]

[…] Common mental health problems like stress, depression and anxiety affect one in six of us in any given week. Research tell us that people with mental health problems contribute £226 billion to the UK economy each year (Mental Health Foundation, 2016). A number of facets of the modern workplace can contribute to the development of mental health problems, examined in the excellent review by Harvey et al (2017) that I reviewed earlier this year. […]

[…] Samuel Harvey et al (2017) examined the workplace factors associated with common mental health problems, proposing a new model for assessing these risks in a systematic review and meta-analysis that I blogged for Mental Elf earlier this year. […]

[…] Sabrina accompanied me as I was still spitting feathers – so much so that I had done a bit of research and found that there are medical studies which prove that work can actually cause or contribute to poor mental health. I’ve included a link at the bottom if you want to read more about this click here […]

[…] with the international evidence and the practice research undertaken over the last ten years. I’ve blogged on Samuel Harvey’s excellent review of risk factors for common mental health proble…, which set out a daring new model describing the pinch points of modern working life that our […]