It has been well established for several decades that both cannabis (Gage et al, 2016) and tobacco smoking (Gurillo et al, 2015) are statistically associated with psychosis. As is often said, correlation does not always equal causation, and in both cases, it has been extremely difficult to clarify the reasons for the association. Two questions have been particularly challenging.

The first question is, what is the direction of causality? In other words, do these drugs have a causative role to play in psychosis, or are they merely more likely to be used by people with psychosis, to alleviate symptoms, or the adverse effects of medication?

The second question is, to what extent are these associations confounded? We know that people who develop psychosis are more likely than average to live in cities, experience childhood stresses and to be drawn from socially disadvantaged groups. The same applies to tobacco and cannabis smoking. So could these associations give rise to a spurious correlation between smoking and psychosis?

To make matters even more complicated, smoking cigarettes and cannabis are themselves highly correlated. Or, more accurately, cannabis smokers constitute a subset of tobacco smokers, since very few people smoke cannabis without tobacco; whether separately or mixed in with cannabis. It is therefore very difficult to study the effects of cannabis alone.

We know both cannabis and tobacco are statistically associated with psychosis, but what is the direction of causality and to what extent are these associations confounded?

Broadly speaking, the assumptions that most people, including health professionals and researchers, tend to hold about these two drugs are opposite:

- In the case of tobacco, the starting assumption is usually that any association is likely to be explained by self-medication or confounding

- With cannabis, however, we are much more inclined to believe in a causal association.

But why make such a distinction between these two drugs? Both are psychoactive substances that are often consumed in adolescence, known to be a critical period of neurodevelopment, and a sensitive period during which many of the risk factors for psychosis can have their strongest effects. The fact that tobacco is legal, and more socially acceptable than cannabis (at least until recently) is irrelevant to their neurobiological effects. Similarly, the fact that cannabis, but not nicotine, can cause psychosis-like symptoms acutely, should not be given too much weight. After all, LSD intoxication causes states that are akin to psychosis, yet hallucinogens have only a modest association with schizophrenia, much less than that of cannabis (Nielsen et al, 2017). That said, this new study focuses on psychotic symptoms, not psychotic disorders (more on that, later).

Do we need to question our long-standing assumptions about tobacco and cannabis?

Methods

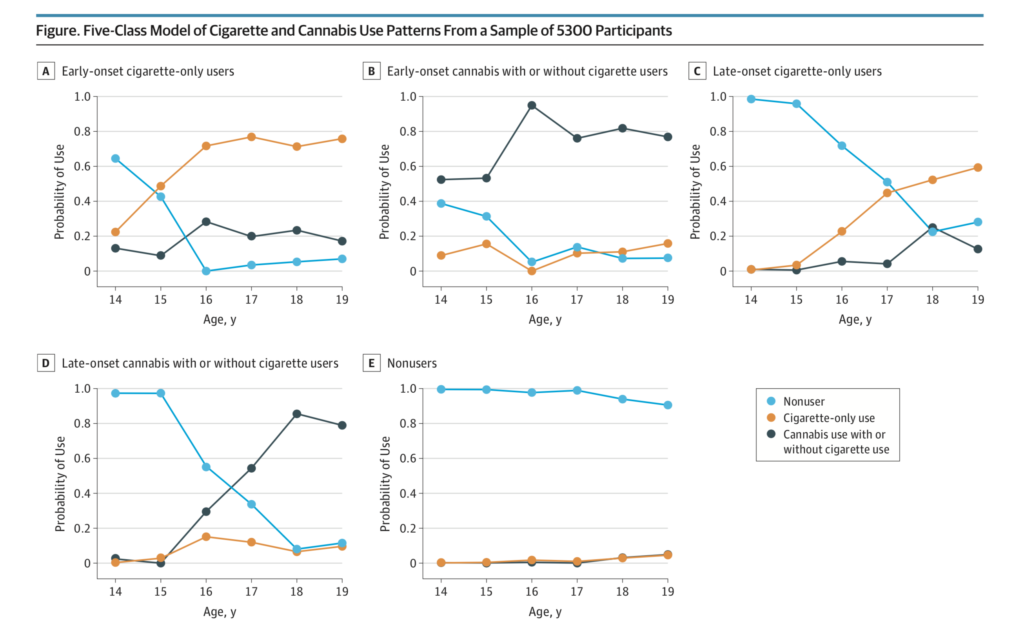

The recent study by Jones et al explores the associations between different combinations of cannabis and tobacco and subclinical psychotic symptoms. The participants were drawn from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents And Children (ALSPAC) cohort study. Cigarette smoking cannabis use was measured at four points between ages 14 and 17. Non-clinical psychotic symptoms were measured at 12 and 18. Latent class analysis was used to classify the participants into five groups based on their tobacco and cannabis use over time. The five classes were described as follows:

A. Early onset tobacco only

B. Early onset cannabis, with or without tobacco

C. Late onset tobacco only

D. Late onset cannabis, with or without tobacco

E. No tobacco or cannabis use

Here is where it gets difficult to interpret. We know from previous studies from this research group, in this cohort, that the vast majority of cannabis smokers use tobacco in their cannabis joints, even if they do not describe themselves as tobacco smokers. A previous study from the same cohort showed that of people who self-reported using cannabis but not tobacco, around 43 out of 46 (94%) revealed that they mixed tobacco in with cannabis when questioned further. Therefore a more accurate description of the five groups is as follows:

A. Early onset tobacco only

B. Early onset cannabis and tobacco

C. Late onset tobacco only

D. Late onset cannabis and tobacco

E. No tobacco or cannabis use

Results

- People in groups A and B (with an early onset of tobacco only, or both cannabis and tobacco) had higher rates of psychotic symptoms at age 18, with odds ratios (OR) of 3-4

- When adjustments were made for potential confounders, the association persisted for cannabis plus tobacco, and diminished for tobacco only, with the OR dropping to 1.8, and the confidence interval crossing 1. This suggests that, if cannabis or tobacco is causally related to psychotic symptoms, the combination of cannabis and tobacco appears to have a stronger effect than tobacco alone

- Late-onset cannabis and tobacco was associated with an increased risk of psychotic symptoms, with an odds ratio of around 3

- Late onset tobacco alone showed no association

- In a separate analysis, the authors investigated the associations between experiencing psychotic symptoms at age 12 (for non-smokers) and subsequently taking up tobacco and/or cannabis smoking. There were no significant associations, although these analyses were poorly powered.

Before adjusting for confounders: cannabis and tobacco were both associated with subsequent psychotic experiences. After adjusting, only cannabis use remained consistently associated with psychotic symptoms.

Strengths and limitations

The study is based on enviable data and the ability to examine changes in smoking habit longitudinally is particularly useful. The research group in Bristol is pre-eminent in this field, so not surprisingly, the quality of the analysis and writing is excellent. I do however have some reservations about some of the methods used.

I suspect the authors chose the latent class approach because it allowed them to make use of all the data, and to include participants with missing data at some timepoints, and this was probably a sensible decision; it does, however, make the study difficult to interpret. For less statistically minded readers, latent class analysis is a sophisticated data reduction technique, which assumes that the population contains two or more sub-types (classes) and uses the data to classify people empirically into different classes on the basis of a set of variables (in this case, smoking status at each time point). Some subjectivity is required on the part of the statistician do decide how many classes are the best fit for the data, but otherwise this is essentially a data-driven approach.

Five-Class Model of Cigarette and Cannabis Use Patterns From a Sample of 5,300 Participants. The probability axis represents the probability of a class member being a nonuser, a cigarette-only user, or a cannabis with or without cigarette user at each time point.

The problem is, there is no guarantee that the classes that emerge from the analysis correspond to clinically recognisable or reproducible subtypes. In this instance, as can be seen in the above figure taken from the paper, the classes do seem to correspond approximately to their descriptions, but the discrimination is far from perfect. For example, while class E is probably the clearest, it still contains a small proportion of people who start smoking at age 18 or 19. More worryingly, in class C, described as ‘late onset cigarette-only users’, only around 50% are using cigarettes at age 18, when the psychotic symptoms were measured. By contrast, in the late onset cannabis group, around 85% were smoking cannabis by age 18. Therefore, if cannabis and tobacco had equal associations with psychotic symptoms, we would expect the ‘late onset cannabis’ group to have a stronger association with psychotic symptoms than the ‘late onset tobacco’ group, simple because 85%, as opposed to 50%, were using the substance in question. So to compare these two groups, and then make inferences about the relative contributions of cannabis and tobacco smoking to the risk of psychotic symptoms, is not really a fair comparison. In my view, a simple classification based on whether subjects smoked or not at age 14 and 18 would have been more readily interpretable and would have allowed clearer conclusions to be drawn.

The methodology of this study make it difficult to interpret the results and apply them in the real world.

Implications

It is very important to keep in mind that the outcome in this study is not schizophrenia or any clinically defined psychotic disorder, but psychotic experiences. There is often a conflation between psychotic symptoms and psychosis, or even schizophrenia, and an assumption that risk factors for psychotic symptoms will generalise to psychosis, but this is ill-founded (David, 2010). Psychotic experiences are not only an order of magnitude more common than psychotic disorders, but they are only weakly associated with the development of diagnosable mental health disorders (Bhavsar et al, 2017). Furthermore, any associations that do exist, seem to be at least as strong for common mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, as for severe mental illnesses including psychosis (Scott et al, 2009). This study, therefore, tells us very little about the relationship between cannabis or tobacco smoking and psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia.

So what can this study add to the existing knowledge about the relationship between smoking and psychotic symptoms? The results are compatible with the view that cannabis has a stronger effect than tobacco, but, since cannabis is almost always taken along with tobacco, and tobacco alone showed some association, an effect of tobacco cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the results are compatible with a synergistic effect whereby the combination of tobacco and cannabis gives rise to psychotic symptoms.

Finally, the study drives another nail into the coffin of the self-medication hypothesis. In children who did not smoke at age 12, the presence of symptoms at age 12 was not associated with taking up cannabis or tobacco smoking later on.

This study supports the view that cannabis has a stronger association with psychotic experiences than tobacco, but an association between tobacco and psychotic symptoms cannot be ruled out.

Links

Primary paper

Jones HJ, Gage SH, Heron J, et al. (2018) Association of Combined Patterns of Tobacco and Cannabis Use in Adolescence With Psychotic Experiences. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):240–246. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4271

Other references

Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S. (2016) Association Between Cannabis and Psychosis: Epidemiologic Evidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:549-556. [PubMed abstract]

Gurillo P, Jauhar S, Murray RM, MacCabe JH. (2015) Does tobacco use cause psychosis? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:718-725.

Nielsen SM, Toftdahl NG, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. (2017) Association between alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit substance abuse and risk of developing schizophrenia: a nationwide population based register study. Psychol Med. 2017;47:1668-1677. [PubMed abstract]

David AS. (2010) Why we need more debate on whether psychotic symptoms lie on a continuum with normality. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1935-1942. [PubMed abstract]

Bhavsar V, Maccabe JH, Hatch SL, Hotopf M, Boydell J, McGuire P. (2017) Subclinical psychotic experiences and subsequent contact with mental health services. BJPsych Open. 2017;3:64-70.

Scott J, Martin G, Bor W, Sawyer M, Clark J, McGrath J. (2009) The prevalence and correlates of hallucinations in Australian adolescents: results from a national survey. Schizophr Res. 2009;107:179-185. [PubMed abstract]

Photo credits

- Photo by Cristian S. on Unsplash

- Photo by Drew Taylor on Unsplash

- Photo by Smoke & Vibe on Unsplash

- Oatsy40 CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Mathew MacQuarrie on Unsplash

Cannabis law reform groups CLEAR and UKCIA have long lobbied for a safer use campaign aimed at encouraging cannabis consumers not to smoke with tobacco, the campaign is called “Tokepure”. The UK government has always refused claiming it would increase the risk of cannabis use. (Anne Milton, Health Secretary, 2013)

I don’t see the point in all this other than providing grants to keep academics in the luxury they are used to. Will it affect anything? Probably not. Is it relevent, no. Do cannabis users care? No. Will it contribute to the overall knowledge on this astonishingly useful plant? Not a lot.

[…] Joint risks? Tobacco and cannabis and psychotic symptoms […]

[…] There has been a bit of a flurry of activity recently with another study expertly analysed in an Elf blog by James MacCabe in […]

[…] for making people ‘high’. But a substantial and ever growing body of evidence links it to an increased risk of psychosis (Gage, Hickman, & Zammit, 2016), and there is evidence of an association with depression and […]

[…] blog by James MacCabe from last year covers this topic […]

[…] blog by James MacCabe from last year covers this topic […]