Last month, Public Health Scotland reported that 833 people had died by suicide in 2019, while suicide rate for males was three times higher compared to females (Scottish Public Health Observatory, 2020). Earlier in the year, the Office for National Statistics report for England and Wales showed 5,691 deaths by suicide in 2019 (ONS, 2019). Every single one of these deaths is a tragedy and we must get better at supporting people who experience suicidal thoughts, and at preventing people from feeling suicidal in the first place.

Studies about online support for people with suicidal thoughts tend to focus on evaluating tools such as apps, or the impact of online support, or the characteristics of those who seek help. A recent study by Lucy Biddle and colleagues is interesting because it goes beyond looking at whether people seek information and support on the internet when suicidal, to asking about their experiences of online help (Biddle et al, 2020). I have a personal and professional interest in this, having been a user of online support provided by both formal services and through peer support communities, as well as being involved in conversations about how to ensure people can access support when they need it, including online.

It’s unusual for research studies to look at what people think of accessing online support for people who are suicidal.

Methods

53 individuals were interviewed by researchers. Participants were selected from three groups:

- Community-based sample of young people (21–23 years) from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children reporting suicide-related internet use in a questionnaire

- Adult hospital patients presenting to the Emergency Departments of two major hospitals in South West England following a suicide attempt and reporting suicide-related internet use when assessed

- Community-based sample of adults who had reported suicide-related internet use in an online survey by Samaritans

The interviews were supported by a topic guide to ensure consistency, but the structure of the questions was flexible and led by the direction of the participant. A coding scheme was developed to explore emerged themes and identify similarities and differences on data related to help use.

Results

All participants reported suicidal thoughts or self-harm, with 34 describing a suicide attempt. 51/53 participants reported viewing suicide-related online help content, with a fifth of them only viewing this indirectly, rather than having deliberately searched for it; for example as a “pop-up” or because a clinician directed them to it.

Negative experiences are highlighted in the paper:

- These included the online support feeling too impersonal or “corporate”, only providing information and lack of age specific content. Interestingly, younger participants felt there was a lack of information for young people, whereas older people felt it was too focused on younger age groups.

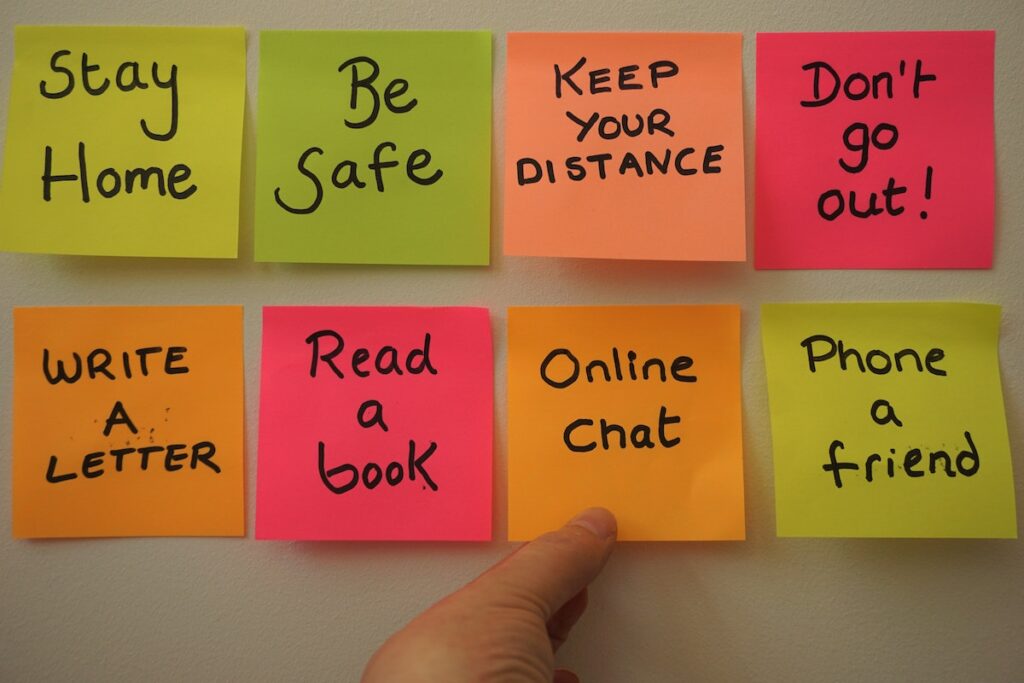

- The limitations of signposting were also highlighted, as providing potentially insensitive or unrealistic advice. For example, in places where social support is not an option, or when people experience or fear stigma (if they seek support), lack of energy or motivation.

Positive experiences and suggestions for improvements to support were also discussed by participants:

- There were frequent suggestions that online instant messaging and live chat would be beneficial in providing immediate support.

- Online forums were also identified commonly by participants as options to facilitate peer support and community, with discussion also about the need for professional presence through affiliation with support providers or organisations to ensure it was a safe space.

- Lived experience content was also highlighted by participants as valuable to offer “hope, inspiration to get better, personal connection”.

- Self-help tools rather than articles and signposting to “real world” support seemed preferred by some participants.

Here’s where you need to go for help, but here’s where you need to go for inspiration’ [… ] that would have helped me at the time.

Participants discussed the benefits of online peer support and messages of hope and inspiration, but also the impersonal character of resources and limitations of signposting.

Conclusions

One of the important findings noted by researchers is that engagement varied across levels of distress. Participants were less likely to engage in online support when suicidal thoughts were most severe. Participants criticised online support as being impersonal and too focused on information giving. They highlighted the need to focus on personal connection, tangible actions and strategies, and immediate responses. This included interactive support such as live chat, forums and lived experience content. Participants referred to positive experiences of using these where they had been available.

The paper concludes that the findings of this study suggested a need to change the way online help services are delivered to ensure that they meet users’ needs and are effective in preventing suicide and supporting people when they are in distress. Further research to consider when and why people access online support and how they can best be engaged is suggested. In particular, further research on how to “retain” people who are experiencing severe suicidal thoughts is suggested, which will be important given the finding that those people are less likely to search out and engage with support.

Once you’ve already made the effort to look for online help, why are you then going to do something else and pick up the phone […] it’s so much effort when it’s easier to go the other way.

This study highlights the need to focus on personal connection, tangible actions and strategies, and immediate responses to support people who are suicidal. This included interactive support such as live chat, forums and lived experience content.

Strengths and limitations

The interview style used, with individuals encouraged to talk about their experiences, and interviewers being led by them, supported by a topic guide to ensure core areas were covered, allowed for in depth exploration of the issues identified by participants. This feels important, not only for the research, but to also allow participants to remain in control of their own narrative and share the parts of their experience. Analysis and data collection happened at the same time which is another strength, allowing for understanding to develop as the study progressed. The inclusion of quotes from participants adds depth and value to the paper.

Another key strength is that the research steering group included two advisers with lived experience of suicidal thoughts and internet use. This should be the norm in mental health research, with their knowledge, experience and advice valued as equal partners alongside others involved in the group, but all too frequently it is not.

53 adults were interviewed between 2014 and 2016 and were only interviewed if they were English speaking which means that there is no perspective included on whether there is adequate support for speakers of other languages in the UK. As is frequently the case, a higher proportion of females (31) were interviewed than males (22), which could also impact on the findings.

A strength of the study is that participants came from more than one “source”: young people, hospital patients who had presented at Emergency Departments, and adults who had responded to a Samaritans survey. The researchers were able to include the experiences of people with different backgrounds, across age ranges, with varying degrees, or no contact with services, those who had sought medical or emotional support, and those experiencing lower levels of distress, as well as those with significant levels of distress and those who had harmed themselves.

The study design allowed participants to express their feelings and navigate through their own narratives, while providing a safe space to do so. A key strength was the inclusion of consultants with lived experience, which should be the norm in mental health research.

Implications for practice

Often, I have been involved in discussions around online support which begin with “we need a website” or worse still “we need an app” (which is often basically just a mobile optimised website) where the main aim is to provide information and self-help advice. This paper demonstrates an explicit “ask” from participants for live, interactive, personal support, which facilitates emotional connection and community. The lived experience of those who have accessed this kind of live online support chimes with my own experience of seeking connection when in distress – not looking for solutions, but looking for understanding and a personal response. This is an important call for those who are involved in service and digital design in this field.

The criticisms around impersonal information and sometimes unrealistic advice and suggestions provided by websites and online help should be considered by services and organisations as they work to improve and enhance their online support options. Additionally, the emphasis placed on the value of content provided from the perspective of those with lived experience, and the hope and insight that can offer, should be acted upon in improving online help offers.

Only a fifth of participants reached online help indirectly for example through a pop-up or suggested link. This suggests that more work could be done in targeting this support at people who may need it.

Lastly, ensuring that people who have lived experience are included in the design and where appropriate delivery of services online, as equal partners, is vital. Participants spoke of the understanding and often hope that can offer, which can be so important in times of distress and crisis.

Peers and communities of people online with lived experience, listening to and supporting each other is not new. Forums and chatrooms for mental health, illness, condition or experience specific areas have been around almost as long as the internet and many of us have used them for years. We know their value, and I have countless peers who have depended on such support. Over recent months we have seen an increase in both lived/living experience support online (such as Mad COVID) and organisations/services developing their digital presence and support (such as Beat’s online chat support groups and one to ones, and Breathing Space piloting web chat support). This study will hopefully inform and encourage further, long term digital support developments, with the experiences of those who need them at their centre.

I read some stories and I didn’t see them as anecdotes. I saw them as a very real and very true… it gave me some courage…

This paper demonstrates an explicit need from people with lived experience for live, interactive, personal support, which facilitates emotional connection and community.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Biddle, L., Derges, J., Goldsmith, C. et al. (2020) Online help for people with suicidal thoughts provided by charities and healthcare organisations: a qualitative study of users’ perceptions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 1157–1166 (2020).

Other references

Suicide: Key Points. Scottish Public Health Observatory Website, last accessed 3 Dec 2020 https://www.scotpho.org.uk/health-wellbeing-and-disease/suicide/key-points

Suicides in England and Wales: 2019 registrations, ONS Website last accessed 3 Dec 2020 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2019registrations

Mad COVID website, last accessed 3 Dec 2020 https://madcovid.wordpress.com/

Beat Website, last accessed 3 Dec 2020 https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/

Breathing Space website, last accessed 3 Dec 2020 https://breathingspace.scot/how-we-can-help/webchat-pilot-project/

Photo credits

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

- Photo by Jurica Koletić on Unsplash

- Photo by freestocks on Unsplash

- Photo by Matt Nelson on Unsplash