Loneliness is an increasing public health concern that is largely ignored in mental health service delivery and policy. Chronic loneliness is experienced by approximately 10-15% of the general population across all ages (Jopling K. et al, 2016). Feelings of loneliness are more prevalent among people with mental health problems than in the general population, with over 80% of people with psychosis reporting loneliness (Stain HJ. et al, 2012) and identifying loneliness as a major challenge in their recovery journey (Morgan VA. et al, 2011). Despite this, there is still a paucity of research about loneliness in psychosis, and many existing psychosocial interventions overlook loneliness as a vital treatment target.

In order to clarify our understanding of the factors that contribute to loneliness severity in psychosis, an important question arises: How is loneliness related to psychological and social factors in individuals with psychosis? A recent systematic review by Michelle Lim and colleagues (2018) sets out to review empirical studies that recruited a clinical population of people with a diagnosis of psychosis, and answer this question based on the understanding of how loneliness was measured in these studies and what the methodological quality was.

Loneliness is an increasing public health concern that’s largely ignored in mental health service delivery and policy.

Methods

The studies included in the review assessed loneliness either as a main outcome or as an associated variable in adults with a clinical diagnosis of psychosis. Predictors or correlates of loneliness needed to be psychological variables, including cognition, personality, mental health symptom, behavioural variables, and psychosocial treatment.

Four databases and 14 relevant journals were searched, and a number of experts were consulted about extra studies. Case studies, conference papers, review papers, and qualitative studies were excluded. The authors assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the widely accepted PRISMA guidelines, although quality scores for each study were not reported in the review.

In total, 1,762 abstracts were screened, of which 10 were eligible for inclusion in the review. The samples were recruited from mixed sources such as outpatient community, inpatient, or a combination of the two settings. All studies were published between 1980 and 2016. Most of the studies used valid and reliable loneliness measures such as the UCLA Loneliness scale (Russell D, 1996) and the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (de Jong-Gierveld J. et al, 1985), however 3 studies measured loneliness in a simpler way: present vs. absent, or the number of days one felt lonely in the past week.

Seven of the 10 included studies used a valid and reliable loneliness measure such as the UCLA Loneliness scale or the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale.

Results

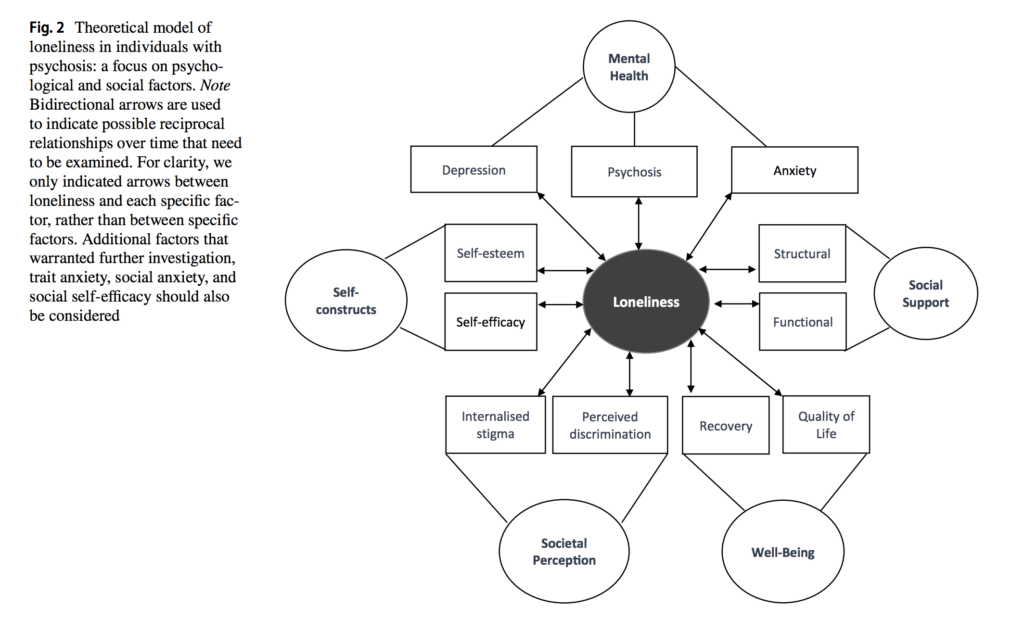

The authors put forth a theoretical model of loneliness in psychosis including five factors: mental health symptoms, social support, well-being factors, societal perceptions and self-constructs. These psychological and social factors may affect loneliness in people with psychosis based on the results of the included studies.

Mental health symptoms: depression, psychosis, and anxiety

- Depression was greatly associated with loneliness in all the six studies that measured depression, although one study found that depression did not independently predict loneliness when considering other factors simultaneously

- Findings on psychotic symptom severity were contradictory. One study found that positive and negative symptoms were associated with the number of lonely days, but two studies found no relationship.

- Anxiety partly mediated the relationship between loneliness and paranoia among people with first-episode psychosis in one study. However, anxiety was induced and measured through experiment rather than trait anxiety (a general tendency to experience anxiety) in that study.

Social support: functional and structural indicators

- Lower loneliness was consistently associated with functional aspects of social support, e.g. better perceived social support and access to a confidant

- Structural indicator of social support (the number of social contacts) was not related to loneliness in one study.

Well-being: quality of life and recovery

- One study measured quality of life and recovery, and found that greater loneliness was correlated to poorer quality of life

- Lower loneliness was only associated with better recovery through improved quality of life.

Social perceptions: internalised stigma and perceived discrimination

- Loneliness was not only significantly associated with internalised stigma (the attitudes and reactions of the stigmatised themselves who accept negative stereotypes of mental disorders), but also completely mediated the relationship between internalised stigma and depression

- The relationship between perceived discrimination and loneliness was partly explained by low self-esteem.

Self-constructs: self-esteem and self-efficacy

- Low self-esteem directly or indirectly (via a tendency to seek support) exacerbated loneliness

- Although poorer self-efficacy was correlated with more severe loneliness, the association was not significant after accounting for other factors, such as psychosocial factors, objective indicators and psychiatric factors.

Theoretical model of loneliness in individuals with psychosis: a focus on psychological and social factors. Click to view full size.

Conclusions

Research that helps us understand the relationships between loneliness and relevant factors in people with psychosis remains at its infancy due to a lack of high quality studies. Considering the important role of loneliness in recovery from psychosis, a multi-aspect psychosocial intervention which specifically measures and targets loneliness is sorely needed.

Based on the results of this review, targeting psychological and social factors, such as mental health, social support, well-being, societal perceptions and self-constructs, may alleviate loneliness and should be measured in loneliness interventions. Additionally, trait anxiety, social anxiety, social self-efficacy and social cognition deficits were not a focus in any of the included studies and need more examination in future research.

Targeting psychological and social factors, such as mental health, social support, well-being, societal perceptions and self-constructs, may alleviate loneliness and should be measured in loneliness interventions.

Strengths and limitations

The reviewers conducted a systematic literature search and followed PRISMA guidelines. All studies were independently assessed for inclusion and methodological quality by two raters. The authors consulted several researchers for related unpublished studies, however there might be publication bias as the database searches conducted were all of published studies and only those in English were included.

One of the greatest issues for the reviewers is the methodological heterogeneity across the included studies. The heterogeneity in the measurement of loneliness and psychotic symptom severity limits their understanding of the relationship between loneliness and psychotic symptoms. The selected studies had different study aims and disparate variables of interest, so there were no comparable results for some isolated variables in the review. For example, anxiety as a related mental health factor was only measured in one study. Thus, in several cases, clear conclusions from synthesised findings were not possible. However, as the authors posited, the isolated variables may offer an indication of the potential influence on loneliness and psychosis in this area of research at its early stage.

Another concern is related to study design. Nine studies were cross-sectional design and one study involved an anxiety-induction experiment. The results within a single time point precluded interferences regarding causal relationships between loneliness and outlined variables. The sample size of four studies was under 100, and these studies might not have adequate statistical power to detect effects. Data from different recruitment sources were combined for analyses, but the sources for each study were not included in the table. This raises concern in terms of generalisability.

The authors acknowledged that the conclusions drawn in the review were limited by the poor methodological quality of the selected studies, but they did not fully report their quality assessment results for each study or how exactly the poor quality may affect study results. It is also unclear which studies have taken into account confounding variables or which confounding variables have been adjusted for in the analyses. It would be better if they could provide a supplementary document detailing relevant information.

The relationship between loneliness and psychosis remains poorly understood due to a lack of high quality studies.

Implications for practice

This review proposed a new model of loneliness in psychosis, and suggested that the factors identified in the review should be priorities for further research. Longitudinal study design would perhaps be beneficial to understand the causal relationships between each factor and loneliness over time.

Loneliness in psychosis is an important research question. The findings from this review highlight the necessity of being proactive in identifying people in social need, followed by adequately responding to their need. The authors advocate psychosocial interventions that specifically target loneliness in people with psychosis, such as cognitively restructuring how an individual perceives their interpersonal relationships, strength-based approaches which promote positive emotions, and positive social interactions that build beneficial relationships.

Whilst I wish a single intervention could solve all the problems, this review has strengthened my realisation that determinants of social relationships exist on multiple levels. Therefore, a personalised response to loneliness is important. It is vital for practitioners to have in-depth discussions with mental health service users about their circumstances, needs and wishes, and then endeavour to offer support and meet these needs. Additionally, the modest impact of existing loneliness interventions implies the importance of broader, indirect approaches which may be more effective at changing the chronic state of loneliness (Mann F. et al, 2017). For example efforts to facilitate social relationships should be accompanied by policies to attenuate inequality and boost employment, education and housing opportunities. The inclusion of loneliness as one of the outcomes in these policies should also be a priority.

Designing a psychosocial intervention that directly targets loneliness would be highly beneficial for people with psychosis.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Lim MH, Gleeson JFM, Alvarez-Jimenez M and Penn DL (2018). Loneliness in psychosis: a systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 53(3): 221-238.

Other references

Jopling, K and Sserwanja I (2016). Loneliness Across the Life Course: A Rapid Review of The Evidence. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, UK Branch.

Stain HJ, Galletly CA, Clark S, et al (2012). Understanding the social costs of psychosis: The experience of adults affected by psychosis identified within the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46(9): 879-889.

Morgan VA, Waterreus A, Jablensky A, et al (2011). People living with psychotic illness 2010. Report on the second Australian national survey of psychotic illness. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra.

Russell DW (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment 66(1): 20-40.

de Jong-Gierveld J, Kamphuis F (1985). The development of a Rasch-Type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement 9(3): 289-299.

Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B, et al (2017). A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52(6): 627-638.

Photo credits

- Photo by Iz zy on Unsplash

- Photo by Chetan Hireholi on Unsplash

- Photo by Ken Treloar on Unsplash

A very well researched and evidenced summary!

Hello Jingyi Wang

I liked your paper very much. I am a Clinical Professor in Psychiatry, UBC and a Consultant Psychiatrist in Vancouver. I am planning to do some work in the area of Loneliness and would like to collaborate with you if possible.

Thank you very much for your interest in my blog about the review written by Michelle Lim! It’s great to know that you are planning to do some work in the area of loneliness. I am curious about the collaboration and what I could possibly offer. May I know more information about it? My email address is jingyi.wang.13@ucl.ac.uk

Thanks a lot!