South Africa is home to the largest population of People Living with HIV/Aids (PLWHA) in the world (19%) (UNAIDS, 2019); however significant medical advancements such as, the development of the world’s largest antiretroviral treatment (ART) program, mean Aids-related deaths are now an anomaly rather than the expectation (Lilian et al., 2020).

Despite this progress, stigma towards PLWHA persists and threatens to undermine the efficacy of the HIV/Aids response; contributing to negative physical, social and mental health outcomes such as loss of livelihood, poor access to healthcare, and feelings of worthlessness (“HIV Stigma and Discrimination”, 2019).

HIV stigma is often rooted in fear, misinformation and the perception of HIV as an ‘illness of the immoral’, associated with culturally taboo behaviours including sex-work, drug use and homosexuality (“HIV Stigma and Discrimination”, 2019). Unsurprisingly, a robust link between stigmatisation and depressive symptoms exists amongst PLWHA with certain subpopulations such as low-income women more vulnerable to the harmful consequences of this (Wingwood et al.,2008). HIV stigma can be conceptualised as a combination of enacted stigma (discrimination from others), anticipated stigma (the anticipation of future discrimination due to the existence of negative attitudes) and internalised stigma (self-direction of negative beliefs and attitudes) (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, 2009).

Through systematically reviewing existing literature the study authors sought to investigate the relationship between HIV stigma and depressive symptoms across different subpopulations in South Africa and identify potential moderators and mediators of this relationship.

Despite improvements in the quality of life and life expectancy of PLWHA in South Africa as a result of medical advancements, HIV stigma remains a threat to mental and physical wellbeing.

Methods

A keyword search of four bibliographic databases (CINAHL, Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science) and two grey literature websites was conducted. After screening studies for relevance and assessing for eligibility, 14 studies were included in the final review. Cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies were appraised using an adaption of the Cambridge Quality checklist and Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form respectively, then categorised into high, fair, or low quality. Due to the diversity of study characteristics and measurement tools, a narrative synthesis approach was employed to review data. Most of the studies sampled adults (n=6), who were either initiated on ART (n=3), experiencing chronic pain (n=1), exclusively female (n=1) or racially diverse. The additional studies sampled pregnant women (n=2), mothers (n=2) and adolescents (n=3).

Results

What is the relationship between HIV stigma and depressive symptoms amongst different subpopulations of People Living with HIV/Aids (PLWHA) in South Africa?

- High levels of HIV stigma and depressive symptoms are reported in this review, with a significant positive relationship between the two, observed across all studies after controlling for sociodemographic variables and complex covariates

- The strength of this association was greatest for internalised stigma which exceeded other forms of stigma in terms of its link with depression

- Subpopulations such as females and adolescents were found to be more vulnerable

- Findings from the prospective studies were inconsistent:

- one study found that stigma did not predict depression despite the cross-sectional association,

- whereas the other found that depression predicted internalised stigma over time suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship.

What are the moderators and mediators of this relationship?

- The moderators and mediators of this relationship were less clear

- Social support was not found to explain the relationship between stigma and depressive symptoms in any of the adult samples

- However, findings from the adolescent sample did demonstrate a moderating effect, although it is noted that additional factors such as self-esteem may have also contributed

- Interestingly, amongst pregnant women starting ART, stigma was found to moderate the relationships between social support and depressive symptoms.

A positive association is suggested between all forms of HIV stigma and depressive symptoms in people living with HIV/Aids.

Conclusions

- People Living with HIV/Aids (PLWHA) who face more stigma are also more susceptible to depressive symptoms with internalised stigma presenting an especially harmful threat to wellbeing

- Women and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the adverse psychological effects of stigma

- Evidence suggests that social support may have a protective effect for adolescents.

Women and adolescents with HIV/Aids are particularly vulnerable to the adverse psychological effects of stigmatisation, this new study finds.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first comprehensive review of the relationship between HIV stigma and depressive symptoms amongst People Living with HIV/Aids (PLWHA) in South Africa; and given the previous exclusion of key vulnerable groups such as sub-Saharan Africans and adolescents from the majority of research, the authors’ exploration of heterogeneity amongst different subpopulations is a key strength.

The use of Narrative Synthesis is a potential limitation, with critics suggesting that the approach lacks transparency and is subject to author interpretation comprising the reliability of findings. However, given the diversity of methodologies used within included studies, the approach is appropriate allowing for a comprehensive synthesis and exploration of findings.

The majority of studies scored low in terms of quality, however, this may be indicative of the rigorous approach to assessing quality and eligibility adopted by the authors. For instance, at multiple points throughout the review aspects of the methodology were independently reviewed by an additional researcher, substantially reducing the influence of researcher bias.

Inconsistencies in methodology and sampling across studies impacted the authors’ abilities to draw clear conclusions. For example, few conducted prospective analyses thus limiting the causal inferences that could be made; moreover, few measured moderating/mediating effects or examined distinct forms of stigma further contributing to a limited understanding of the nature of the relationship between HIV stigma and depression.

The study findings highlighted disparities in the effects of HIV stigma for different subpopulations, however, did not account for factors such as race and sexuality. Most studies omitted racial demographic data but, those that did not consisted of almost exclusively black samples. Research has shown correlations between HIV stigma, gender and racial discrimination and depression, highlighting the value of considering potential intersections between HIV stigma and other forms of stigma when conducting research (Logie et al., 2013). The lack of racial diversity limits the generalisability of findings and may conceal the potential interactive/additive effects of converging forms of stigma; however, the authors do consider this in their discussion. It is also important to note that many of the aforementioned limitations point towards existing gaps in the literature and therefore cannot be attributed to the authors of this review.

The majority of included studies omitted sociodemographic information such as race and sexuality or were racially homogenous, thus limiting generalisability and potentially obscuring the effects of converging forms of stigma.

Implications for practice

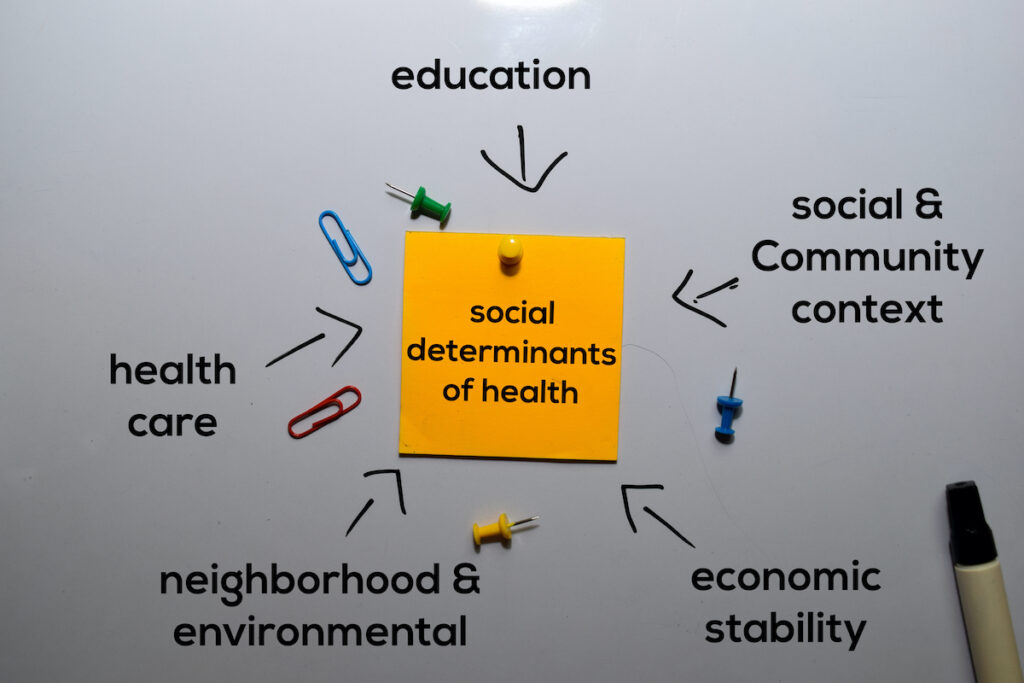

Whilst directionality remains unclear, it seems that by pushing people to the margins of society, stigma may contribute to emotional distress amongst People Living with HIV/Aids (PLWHA) – which can precede physical health declines (Chaudoir et al., 2011). Therefore, the findings of this review underscore the value of developing policies and interventions that target HIV stigma to improve individual wellbeing whilst optimising the HIV treatment and prevention response.

The UK-based HIV/Aids charity Avert highlight the value of adopting approaches that champion education, empowerment, inclusion, and protection when tackling HIV stigma (“HIV Stigma and Discrimination”, 2019). Community-based projects may have the power to reshape social perception. For instance, The Stigma Reduction Initiative based in Ethiopia, Zambia and Kenya demonstrated that when faith leaders developed strategies to reduce stigma and discrimination based on lived experiences of community members, it was transformational in empowering PLWHA and influencing attitudes (Lennon, 2014). In countries like South Africa where attitudes are often shaped by religious beliefs, the engagement of faith leaders could be an invaluable tool.

The strong association between internalised stigma and depression emphasises the importance of taking steps to support PLWHA in coming to terms with their diagnosis. Cognitive therapies can be a useful tool for equipping them with valuable coping skills, whilst alternative interventions aimed at enhancing economic empowerment and self-esteem have the potential to challenge the negative self-perceptions central to internalised stigma (Earnshaw et al.,2018).

The findings also highlight the value of focussing resources on the groups most vulnerable to the adverse psychological effects of stigma (i.e. females and young people), particularly within resource-limited contexts. Social support may be a worthwhile target of early intervention to limit the harmful effects of HIV stigma for adolescents.

This study lays the foundations for further investigation of the relationship between HIV stigma and depression, for instance, longitudinal research to determine the directionality and identify causality. Moreover, additional research into the mediators and moderators of this relationship could uncover more potential treatment targets.

Community-based approaches can tackle HIV stigma by empowering people living with HIV/Aids and reshaping social perceptions.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

MacLean, J., & Wetherall, K. (2021). The Association between HIV-Stigma and Depressive Symptoms among People Living with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review of Studies Conducted in South Africa. Journal of Affective Disorders, 287, 125-137. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.027

Other references

Bernard, C., Dabis, F., & de Rekeneire, N. (2017). Prevalence and factors associated with depression in people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 12(8), e0181960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181960

Chaudoir, S., Norton, W., Earnshaw, V., Moneyham, L., Mugavero, M., & Hiers, K. (2011). Coping with HIV Stigma: Do Proactive Coping and Spiritual Peace Buffer the Effect of Stigma on Depression?. AIDS And Behavior, 16(8), 2382-2391. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0039-3

Earnshaw, V., Bogart, L., Laurenceau, J., Chan, B., Maughan-Brown, B., & Dietrich, J. et al. (2018). Internalized HIV stigma, ART initiation and HIV-1 RNA suppression in South Africa: exploring avoidant coping as a longitudinal mediator. Journal Of The International AIDS Society, 21(10), e25198. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25198

Earnshaw, V., & Chaudoir, S. (2009). From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures. AIDS And Behavior, 13(6). doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3

HIV Stigma and Discrimination. (2019). Retrieved 24 February 2022, from https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/stigma-discrimination

Lennon., J. (2014). Addressing stigma and discrimination through faith leaders [Blog]. Retrieved from https://www.avert.org/news/addressing-stigma-and-discrimination-through-faith-leaders

Logie, C., James, L., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. (2013). Associations Between HIV-Related Stigma, Racial Discrimination, Gender Discrimination, and Depression Among HIV-Positive African, Caribbean, and Black Women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care And Stds, 27(2), 114-122. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0296

UNAIDS. The Gap Report. Accessed 13 June 2019 from http://files.unaids.org/en/ media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_r eport_en.pdf.

Wingood, G.M., Reddy, P., Peterson, S.H., DiClemente, R.J., Nogoduka, C., Braxton, N., MBewu, A.D., 2008. HIV stigma and mental health status among women living with HIV in the Western Cape, South Africa. South African Journal of Science 104 (5-6), 237–240.

Photo credits

- Photo by Anaya Katlego on Unsplash

- Photo by Johannes Krupinski on Unsplash