This is the first in a new series of Mental Elf blogs produced in partnership with the British Journal of Psychiatry. Each month we will select a new paper from the BJPsych to be blogged by a young psychiatrist with research experience. We’re really excited about this new venture and look forward to highlighting important new evidence that has implications for practice. And now, over to Joe Hayes for the first blog!

There are signs that we are failing people with depression. A recent study published in BJPsych found that only 1 in 5 people with depression in high-income countries, and 1 in 27 people in low- and middle-income countries, received adequate treatment (Thornicroft et al., 2016).

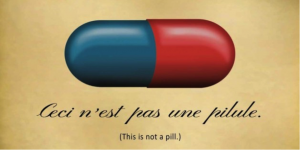

However, findings such as these seem to be at odds with reports of overtreatment and overdiagnosis (Dowrick & Frances, 2013). Moreover, it is this story that seems to capture the public imagination. The other powerful narrative has been that antidepressants are no more effective than placebo and that pharmaceutical companies cannot be trusted because they have hidden this from us.

Undertreatment of depression? Overtreatment of depression? How can we get things “just right”?

We are repeatedly told that the increasing placebo effect is the reason for drug companies withdrawal from psychiatric drug development. Professor Irving Kirsch and colleagues played an important part in developing this narrative with their highly cited meta-analysis (Kirsch et al., 2008), which concluded:

The overall effect of new-generation antidepressant medications is below recommended criteria for clinical significance. We also find that efficacy reaches clinical significance only in trials involving the most extremely depressed patients, and that this pattern is due to a decrease in the response to placebo rather than an increase in the response to medication. (Kirsch et al., 2008)

This finding has now been refuted by a number of study level and individual-participant level meta-analyses (Melander et al., 2008; Rabinowitz et al., 2016). Further, the study by Kirsch et al. has been labelled as one of the 10 most controversial ever published in psychology (a pretty impressive claim to fame given that this list includes the Stanford prison experiment, the Milgram “shock experiments” and the conditioning of Little Albert).

Despite the conflicting evidence, the idea that baseline severity impacts on antidepressant treatment effectiveness was taken up wholeheartedly by NICE and other agencies. They advocate for the use of psychotherapy, in particular cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), in people with mild/moderate depression. Interestingly, whilst this was going on, albeit more quietly, similar findings were being reported concerning psychotherapy: CBT might only be effective when depression is most severe and may be little better than placebo (Driessen et al., 2010; Cuijpers et al., 2010a; Cuijpers et al., 2010b). This phenomena was described in a Mental Elf blog from last year.

This new meta-analysis published in the BJPsych (Furukawa et al, 2017) seeks to address the issue of initial severity effects by identifying all randomised controlled trials of CBT versus pill-placebo and accessing and meta-analysing individual-participant data (IPD-MA).

This BJPsych individual-participant meta-analysis compared CBT with pill-placebo.

Methods

Study selection

Traditionally meta-analysis involves combining and analysing quantitative evidence from a number of studies to produce a pooled effect estimate. An alternative approach, which is becoming increasingly used, is IPD-MA. In this design the researcher obtains raw patient level data from each study identified as relevant. This approach has particular strengths: it increases the power to detect differential treatment effects across individuals and makes it possible to look at the influence of baseline characteristics (in this case illness severity) on outcome.

Studies were eligible if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) who received an intervention of face-to-face individual or group CBT, with a control group of individuals receiving pill-placebo. The search for eligible RCTs was comprehensive and used a number of databases, but did not search grey literature or approach researchers in the field to identify potentially unpublished studies. Authors were then contacted, and individual-level participant data was requested.

Intervention and control

The authors state that they chose pill-placebo as the control as “traditional control conditions… such as waiting list, no treatment or treatment as usual, are too heterogeneous and may be affected by publication bias” additionally a pill-placebo control will account for “non-specific placebo effects including expectation, attention and support”. Whilst these exclusions are logical, we must be aware that this analysis is therefore likely to exclude a large number of trials of CBT for depression.

Depression outcome

The primary outcome was change in Hamilton Rating scale for Depression (HAM-D), which is researcher administered, and the secondary outcome was change in Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which is a self-report measure. Both these scales are widely used in depression research, but a number of issues have been raised with them, especially in delineating clinical significance from statistical significance (Fava et al., 2003; Bech, 2006). Additionally in this meta-analysis, included RCTs used different versions of these scales, with different item questions and numbers of items.

Analyses

To manage the differences in HAM-D and BDI, these scales were standardised within each study. To do this raw scores at baseline and endpoint were divided by study-specific standard deviations. The authors then investigated whether the standardised baseline score modified the effect of the symptom change score (i.e. whether individuals who were initially more depressed demonstrate larger treatment effects). Multiple imputation was used to manage missing data. There is no discussion of why, or to what extent, data were missing, which is a limitation of the paper. Whilst this may be the most appropriate approach, it is likely that data are missing not at random (i.e. that individuals drop out of the RCTs for reasons that are unknown, but not random) (Little et al., 2012).

Results

Studies and participants

Five RCTs were identified as eligible and five sets of individual-patient data were made available by the original investigators; 509 individuals with MDD and 46 with minor depression/dysthymia were included. This is the biggest achievement of this study; that data from all identified RCTs was provided to the authors to be reanalysed. HAM-D was reported in five RCTs and BDI in two. HAM-D reporting was single-blind (assessors were not aware of treatment allocation), BDI reporting was not blind (because it is a self-report measure). The authors report that almost 400 RCTs were excluded because they did not make a comparison with pill-placebo.

Baseline severity and treatment response

There was no statistically significant interaction between baseline HAM-D score and treatment condition (P=0.43) and similarly differences in changes in BDI between CBT and pill-placebo arms were not related to baseline severity. All sensitivity analyses had similar findings. CBT was statistically superior to pill-placebo in the studies using HAM-D as an outcome (standardised mean difference -0.22; 95% confidence interval (CI) -0.42 to -0.02; P=0.03).

Conclusions

The authors conclude baseline severity has little influence on efficacy of CBT. They state that this is potentially in contrast to the relationship between depression severity and efficacy of antidepressant medication. However as discussed, though this isn’t resolved for pharmacotherapy, it looks increasingly likely that baseline severity does not influence antidepressant response either (Weitz et al., 2015) and that differences previously observed are related to methodological limitations and regression toward the mean.

In addition, Furukawa et al. find that CBT leads to greater symptom reduction than pill-placebo. Study level meta-analysis suggests the effect size for antidepressants over pill-placebo may be greater than the effect observed for CBT (Turner et al., 2008), but recently traditional meta-analysis and IPD-MA have found no difference between CBT and antidepressant medication when compared directly (Amick et al., 2015; Weitz et al. 2015).

Strengths and limitations

This study is most impressive in successfully accessing data from all RCTs that met their inclusion criteria. The methodology applied appears to be the most appropriate use of this data, however the authors admit the study may be underpowered to detect an interaction effect. The conclusion that baseline severity does not influence treatment effects may therefore represent a type II error. The authors also state that they ignored some of the design features of the original RCTs, such as inclusion of specific depression subtypes, primary care patients, pre-randomisation run-in treatment or differing treatment lengths. Some of these features could differentially effect the association between baseline severity and treatment response.

Other limitations, such as the need to combine different HAM-D and BDI scales and the lack of detail about multiple imputation and missing data have already been discussed. Beyond these issues, there is no mention of a protocol for the meta-analysis, and more extensive use of online supplements may have be useful to clarify differences in data from each included RCT.

Other differences in study design or patient characteristics may be important for CBT response.

Potential impact and implications

The authors state that patients can “expect as much benefit from CBT… across its wide range of baseline severity”, a more conservative summing-up might be that there is no evidence that CBT is more efficacious in more severe depression. Furukawa has developed a method of converting effect size to number needed to treat (NNT) (Furukawa, 1999) and results from this study suggest a NNT of 12 with CBT (compared with a NNT of 9 for antidepressants). What is not reported, however, is the 95% CI for the NNT which is likely to be wide.

It is concerning when different methodological approaches give different answers to the same question. It may be that it is not possible to accurately investigate the effects of baseline differences in patient characteristics using study level information (in fact, this may be a form of ecological fallacy) and individual-participant level data is required.

To improve evidence-based practice, pooled individual-participant data needs to become the norm, and this paper is a good example of appropriate data sharing. This type of meta-analysis becomes immediately biased if access to original data is limited. The potential resource and cost implications of contacting study authors, obtaining their individual participant data, inputting and “cleaning” data, resolving data issues and generating a consistent data format, may preclude such studies if systematic searching reveals a large number of relevant original research articles. Additional problems may arise if the required data is historical or the lead authors are not world-renowned psychiatric epidemiologists with considerable sway over their fellow researchers!

Pooling data in IPD-MA is a powerful method of generating evidence, however we need to understand its potential limitations

Conflicts of interest

Joseph Hayes is a trainee editor at the British Journal of Psychiatry. He has never received drug company funding.

Links

Primary paper

Furukawa TA, Weitz ES, Tanaka S, Hollon SD, Hofmann SG, Andersson G, Twisk J, DeRubeis RJ, Dimidjian S, Hegerl U, Mergl R. (2017) Initial severity of depression and efficacy of cognitive–behavioural therapy: individual-participant data meta-analysis of pill-placebo-controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2017 Jan 19:bjp-p.

Other references

Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, Gruber M, Sampson N, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Andrade L, Borges G, Bruffaerts R. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2016 Dec 1:bjp-p.

Dowrick C, Frances A. Medicalising unhappiness: new classification of depression risks more patients being put on drug treatment from which they will not benefit. BMJ. 2013 Dec 9;347(7):f7140.

Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med. 2008 Feb 26;5(2):e45.

Melander H, Salmonson T, Abadie E, van Zwieten-Boot B. A regulatory Apologia—a review of placebo-controlled studies in regulatory submissions of new-generation antidepressants. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 Sep 30;18(9):623-7.

Rabinowitz J, Werbeloff N, Mandel FS, Menard F, Marangell L, Kapur S. Initial depression severity and response to antidepressants v. placebo: patient-level data analysis from 34 randomised controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2016 Nov 1;209(5):427-8.

Driessen E, Cuijpers P, Hollon SD, Dekker JJ. Does pretreatment severity moderate the efficacy of psychological treatment of adult outpatient depression? A meta-analysis.

Cuijpers P, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E, Hollon SD, Andersson G. Efficacy of cognitive–behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010 Mar 1;196(3):173-8.

Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Bohlmeijer E, Hollon SD, Andersson G. The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychological medicine. 2010 Feb 1;40(02):211-23.

Fava M, Evins AE, Dorer DJ, Schoenfeld DA. The problem of the placebo response in clinical trials for psychiatric disorders: culprits, possible remedies, and a novel study design approach. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2003 Apr 18;72(3):115-27.

Bech P. Rating scales in depression: limitations and pitfalls. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2006 Jun;8(2):207.

Little RJ, D’agostino R, Cohen ML, Dickersin K, Emerson SS, Farrar JT, Frangakis C, Hogan JW, Molenberghs G, Murphy SA, Neaton JD. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012 Oct 4;367(14):1355-60.

Weitz ES, Hollon SD, Twisk J, van Straten A, Huibers MJ, David D, DeRubeis RJ, Dimidjian S, Dunlop BW, Cristea IA, Faramarzi M. Baseline depression severity as moderator of depression outcomes between cognitive behavioral therapy vs pharmacotherapy: an individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2015 Nov 1;72(11):1102-9.

Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Jan 17;358(3):252-60.

Amick HR, Gartlehner G, Gaynes BN, Forneris C, Asher GN, Morgan LC, Coker-Schwimmer E, Boland E, Lux LJ, Gaylord S, Bann C. Comparative benefits and harms of second generation antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapies in initial treatment of major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015 Dec 8;351:h6019.

Furukawa TA. From effect size into number needed to treat. The Lancet. 1999 May 15;353(9165):1680.