This systematic review by Stephanie Petty and colleagues aimed to define and explain emotional distress as experienced by people with dementia, to enable care to be more personalised and to improve societal understanding of the experiences of dementia.

Emotional distress is widely experienced in dementia yet lacks a succinct definition. The authors state that emotional distress is different to emotional symptoms of psychiatric disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, agitation), and is different to negative emotions that are not distressing (e.g. boredom).

In this review emotional distress is described as negative emotion expressed with some urgency.

Emotional distress is defined as negative emotion expressed with some urgency.

Methods

The research questions were:

- How can emotional distress be characterised for individuals with dementia?

- What descriptions of emotional distress exist?

- What explanations for emotional distress exist?

Twelve databases were searched to answer this question, using (1) “dement*” and “Alzheimer*” and (2) terms relating to emotion such as “distress”, “lonel*” and “anxi*”. Out of an initial 64,898 titles, a total of 121 eligible papers were found (including journal articles, book sections, a professional group periodical and a charity document) combining personal experiences of people with dementia as well as observations from family members, professional carers and academic researchers.

All subtypes of dementia and a range of living environments were considered to gather a wide range of experiences, including people living in the community, alone, with family, in shared or supported housing, nursing home and residential care, in hospital, in a day care centre and in a hospice.

A computerised language analysis method was used to extract an objective definition of “emotional distress” from these papers, to reduce researcher bias on what truly constituted emotional distress. The analyses identified ‘keywords’ that occurred in the included papers more frequently than would be expected in general language use. The strength of the relationship between the keywords and their neighbouring words was also analysed, to provide a greater depth and breadth of descriptions of emotional experience.

All papers were also read by the research team, and descriptions and explanations of emotional distress were extracted and synthesised. Two methods of analysis were used: (1) for description of distress: corpus-based analysis, (2) for explanations of distress: meta-ethnography.

Results

Explanations of distress were grouped under 6 main concepts:

| Concept | Quote from the review to illustrate |

| Self and loss of self

|

“a nearly complete dismantling of the self I once knew” |

| Social position (including feeling excluded, isolated and criticised)

|

“I feel that I’m not much use to anybody” |

| Relational needs (including cognitive problems, living alone and being dependent on someone else)

|

“feeling lonely despite being surrounded by lots of people” |

| The future (including fearfully anticipation of death)

|

“I thought that was the end of my life” |

| Physical environment (e.g. fears of getting lost due to things being too loud/fast/confusing)

|

“she was constantly looking around nervously as people moved towards or around her” |

| Perception (including hallucinations and reliving past events)

|

“all the adrenaline rush, perspiration, rapid breathing, and heart pounding of a real situation” |

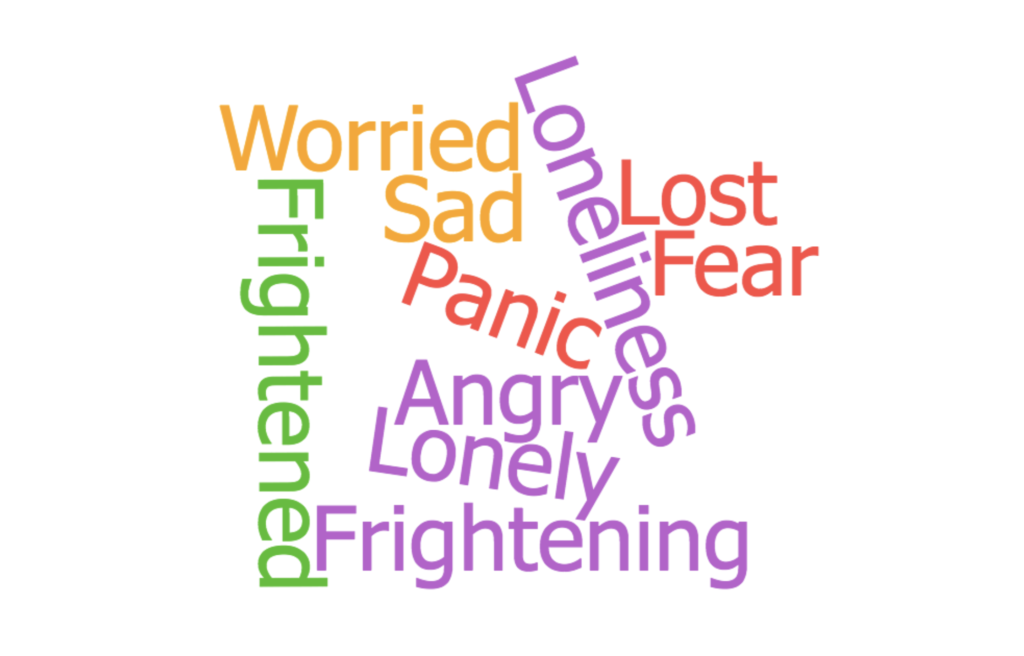

Words used to describe emotional distress

The most common words used by people with dementia to describe their emotional distress were:

- Fear

- Worried

- Frightened

- Lost

- Frightening

- Lonely

- Panic

- Angry

- Loneliness

- Sad

Findings show that individuals with dementia are fearful because they feel they are losing their identities, relationships, freedom, control, social world and increasingly needing to depend on others.

For those without dementia (the carers, family, academics, health professionals) who described what they observed, feelings of anxiety in people with dementia were the most common description, followed by distress.

People with dementia can feel that they are losing their identities.

Conclusions

This paper powerfully highlights the realities of living with dementia; one of the many strengths of using qualitative as well as quantitative techniques.

The authors conclude that receiving a timely diagnosis, feeling valued, depending on others for emotional support, anticipating a hopeful future, maintaining purpose and a continuous sense of self are important to people with dementia and their families – also all difficult concepts to define.

Feeling valued and hopeful about the future is important to people with dementia.

Strengths

The methods of searching were very thorough and the review includes the experiences of a wide range of participants people with dementia; highlighting the individual nature of a diagnosis of dementia. Only studies in English were included, but spanned 14 countries, however these were mostly higher incomes countries.

Limitations

It is not completely clear how emotional distress differs from agitation (restlessness, repetitive behaviour, vocalisations, aggressive behaviours) or neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia (irritability, disinhibition). Agitation is very common in people with dementia and can have many causes (Livingston et al., 2017) including factors stated in this paper as causes of emotional distress: unmet needs, fear or physical environment.

The authors reflect that there was some disagreement over which papers to include, reflecting the difficulty of defining a concept like “emotional distress”. The method of defining these concepts is not validated for qualitative analysis and the software (WordSmith Tools) is programmed to capture British English usually used for academic articles, therefore potentially excluding anything written in other styles, colloquial language, on social media or in diaries, or language that uses specific metaphors or turns of phrase.

A specially created quality tool was used to rate quality of the 121 studies using a points-based system (higher points=higher quality), based on existing tools. The authors state that higher quality papers were prioritised, but it is not clear how this was done. The lower quality studies often had methodological problems such as not adjusting for confounders or discussing alternative explanations, not using a representative sample or accounting for selection bias of the sample (the only type of bias assessed by the quality rating tool). It was also interesting that the results of the paper strongly reflect the original search terms used by the authors but is it not clear whether the WordSmith Tools software accounts for this source of potential bias.

The results of this review may not be generalisable across subtypes or severities of dementia. Most of the participants included had mild dementia, and it was not clear how many participants had which subtype of dementia. Therefore, the authors could not conclude whether experiences differed between subtypes and severities. It could be clinically important to ascertain this, as an emotion-like anxiety could be experienced differently in a person with mild dementia compared to someone with severe dementia, particularly as it may manifest more as agitation in the severe stages. It could also be clinically relevant to observe whether anxiety in mild dementia is qualitatively different from agitated behaviour in advanced dementia.

Finally, the paper makes some conclusions about what may reduce emotional distress in people with dementia. However, as indicated by the authors, perhaps these should be read cautiously as the study concentrates on defining and explaining distress rather than methods of alleviating it.

It is not clear how emotional distress is different from agitation in people with dementia.

Implications for practice

Explanations for emotional distress such as the ‘physical environment’ have clear implications for practice and reinforce the benefits of initiatives like Dementia Friendly Communities.

The feelings of fear associated with ‘the future’ might be somewhat addressed by involving professionals like Admiral Nurses or palliative care teams early in the journey, so that talking about end of life becomes less fearful. From a professional perspective, the earlier the conversation about end of life begins the better; however, from a human perspective talking about death as soon as one has received a diagnosis may not be the most sensitive approach.

This paper adds to the understanding of individual experiences of dementia although it offers minimal practical recommendations for how these insights could be used. While it may have been beyond the scope of this review, being able to identify and characterise emotional distress in people with dementia is most useful when there are also methods to prevent it or ease it.

Feelings of fear associated with thinking about the future could be alleviated by involving professionals like Admiral Nurses. Image © Dementia UK 2017.

Conflicts of interest

None

Links

Primary paper

Petty S, Harvey K, Griffiths A, Coleston DM, Dening T. (2018) Emotional distress with dementia: A systematic review using corpus-based analysis and meta-ethnography. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:679–687. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4870

Other references

Livingston, G., Barber, J., Marston, L., Rapaport, P., Livingston, D., Cousins, S., … Cooper, C. (2017). Prevalence of and associations with agitation in residents with dementia living in care homes: MARQUE cross-sectional study. British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 3(4), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.117.005181

Photo credits

- Photo by Jeremy Wong on Unsplash

- Photo by mari lezhava on Unsplash

- Photo by William Krause on Unsplash