Most people have heard of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a neurodevelopmental difference thought to impact around 1.5% of the UK population (Baxter, Brugha, Erskine, Scheurer, Vos, & Scott, 2015). Prevalence appears to be growing, but in reality, this is largely due to growing awareness (Smiley, Gerstein, & Nelson, 2018) thanks to stereotypical characters such as Sheldon in ‘The Big Bang Theory’. Many could now tell you that ASD has something to do with social and communication difficulties or perhaps obsessive interests, and it is these, in addition to repetitive or restricted behaviours and problems with sensory issues, that define the condition. Characteristics need to be present from early childhood for a diagnosis to be made, however it often isn’t until the inherent difficulties with communication and social interaction become obvious, usually around adolescence, that ASD is first suspected. This has potentially led to a “lost generation” of adults with ASD who have been missed or misdiagnosed with other mental health conditions (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

Up until 2013, autism was predominately considered a childhood condition, but the 5th Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) changed that by acknowledging the possibility of an adult diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). This has led to increased numbers of adults seeking a formal diagnosis (Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015).

Diagnosing ASD in adults can be problematic, not least because high functioning individuals have often developed coping strategies which both mask their difficulties and prevent them coming forward for diagnosis and support (APA, 2013; Happé, Mansour, Barrett, Brown, Abbott, & Charlton, 2016). The risks of ASD being missed increases for women (Bargiela, Steward, & Mandy, 2016; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015) with the ratio of male to female diagnosis being around 4:1 (Baxter et al., 2015). As women present differently to men, their difficulties often don’t become evident until they are older (Giarelli et al, 2010) and they are more likely to internalise rather than externalise their symptoms making them less visible and increasing the likelihood of misdiagnosis (Hull & Mandy, 2017).

A recent systematic review of 4 studies revealed that misdiagnosis of ASD is commonplace with between 2.4 and 9.9% of psychiatric inpatients having undiagnosed autism (Tromans, Chester, Kiani, Alexander, & Brugha, 2018). A further study of a treatment centre for severe psychiatric disabilities found 3.2% of patients were autistic (Nylander & Gillberg, 2001), and another that 2.6% of patients referred to ‘Early Intervention for Psychosis’ met diagnostic criteria for ASD (Davidson, Greenwood, Stansfield, & Wright, 2014). Geurts & Jansen (2012) argue that most adults with autism were known to mental health services before receiving a diagnosis.

This study, by Fusar‑Poli, Brondino, Politi & Aguglia (2020) looks to add to the evidence by exploring the characteristics of 161 adults obtaining their first formal diagnosis of ASD at two Italian university centres, following the revised criteria set by the DSM-5.

Autism in adults frequently goes undiagnosed due to lack of referral to services or symptoms misdiagnosed as psychiatric illnesses.

Methods

161 participants, 79.5% male with an average age of 23, were referred to one of two ASD specialist Italian university services where the revised DSM-5 criteria was used to assess for the condition. Teams carrying out the assessments were composed of psychiatrists and trainees with wide experience of autism.

- A developmental, personal and clinical history was taken from patients and/or family

- The age they were first assessed by a mental health professional and previous diagnoses were recorded

- A detailed assessment for ASD was carried out using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 [ADOS-2] (Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, Risi, Gotham, & Bishop, 2012) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [ADI-R] (Lord, Rutter, & Le Couteur, 1994). Other potential comorbid psychiatric conditions were also assessed

- Severity of deficits in socio-communication, and presence of restricted interests or repetitive behaviours, were measured using the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013)

- Any diagnosis for ASD and/or co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses had to be agreed by all clinical staff.

Results

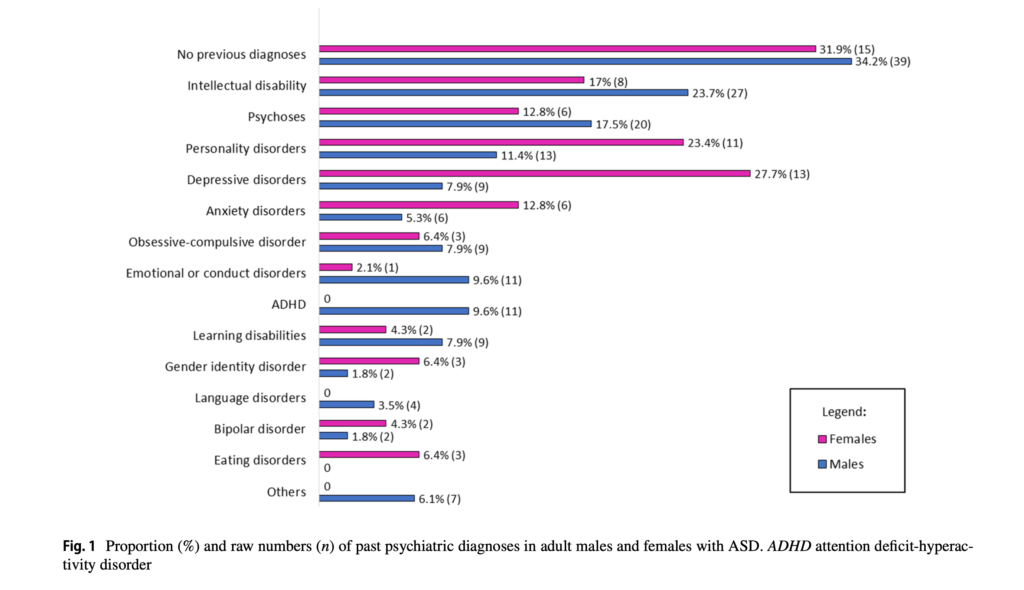

Within the sample the average age for an ASD diagnosis was 22 for men and 26 for women despite 81% of the male and 68% of female participants already having had contact with mental health services. The average amount of time elapsed between first clinical evaluation (by a psychologist or psychiatrist) and ASD diagnosis was 11 years for men and 12 years for women with participants sometimes receiving multiple diagnoses in between.

Fig. 1 Proportion (%) and raw numbers (n) of past psychiatric diagnoses in adult males and females with ASD (reproduced from paper – Fusar-Poli, 2020). View full sized figure

There were a number of psychiatric diagnoses the symptoms of which crossover with those of ASD. Psychotic disorders are characterised by poor social insight, inappropriate social behaviour, and social isolation, all aspects of ASD (Fusar-Poli et al., 2020; Nylander, 2014). Personality disorders (PD) share similar features with ASD such as emotional dysregulation and self-harm (borderline/ emotionally unstable PD), low empathic traits (antisocial PD), social avoidance (avoidant PD) or sameness (obsessive–compulsive PD) (De Cagna, Squillari, Rocchetti, & Fusar-Poli, 2019). Other significant characteristics of ASD such as social withdrawal are associated with depression (Wolf & Ventola, 2014), poor social functioning and social isolation are common in anxiety (Kerns et al., 2016), and repetitive behaviours and/or restricted interests similar to features of OCD (Wu, Rudy, & Storch, 2014).

The average amount of time between first clinical evaluation and receiving a diagnosis of autism was 11 years for men and 12 years for women.

Conclusions

Data from this study revealed that ASD is still poorly recognised by both child and adult psychiatrists with crossover symptoms being confused with other mental health disorders. This can be due to a whole host of reasons, not least that for some, the features of ASD are often masked until limited social and communication abilities cannot keep pace with societal expectations. This often occurs during adolescence when other developmental norms and hormonal changes can disguise the cause of such difficulties.

Autism spectrum disorder is still poorly recognised by child and adult psychiatrists with crossover symptoms being confused with other mental health disorders.

Strengths and limitations

It is recognised by the authors of the study that male participants were over-represented, however this is representative of the male: female ASD ratio within society. It is widely reported that women with autism present differently to men often developing more effective ‘camouflage’ strategies (Bargiela, Steward, & Mandy, 2016; Kenyon, 2014).

Compared to men who tend to externalise difficulties presenting with hyperactivity, poor behaviour and impulsivity, all of which are noticeable to onlookers, women often internalise their difficulties with ‘quieter’ and more subtle issues such as anxiety, depression and eating disorders (Bargiela, Steward, & Mandy, 2016; Mandy et al., 2012). In addition, the ADOS-2, the diagnostic tool for screening ASD, has been developed based on male features of autism and excluding some of the female features (Lai, Lombardo, Auyeung, Chakrabarti, & Baron-Cohen, 2015; Rynkiewicz, 2016), making it more difficult to accurately assess girls and women for an autism diagnosis.

The authors recognise that those included within the study were those who had been referred and were subsequently diagnosed as being on the autistic spectrum, it did not follow up on those that did not receive an ASD diagnosis.

The definition of ASD was standardised across the study, however other prior psychiatric diagnoses were not assessed for or standardised.

The assessment was small and specific to two university centres in Italy, screening and detection of autism in other countries may differ, however the results do mirror findings from other research in Western countries (Geurts & Jansen, 2012; Lai et al., 2019).

This study is small and specific to two university centres in Italy, so results may not be generalisable.

Implications for practice

Not only can recognising the signs of ASD explain behaviours potentially avoiding a mental health diagnosis, but it has huge implications for the choice of treatment for comorbid conditions.

- Being able to get specific support with ASD such as academic/job support or in some cases, disability benefits, could be enough to help support the associated mental health implications

- Understanding that obsessions or repetitive behaviours when symptomatic of ASD, are a fundamental coping strategy and have a calming rather distressing function (Paula-Pérez, 2013), could avoid the need for medication. This is particularly significant as not only will such ASD symptoms not respond to medication, the drugs used to treat them as a symptom of a psychiatric disorder have considerable negative side-effects

- Understanding the social and communication difficulties inherent within ASD could and should have an impact on choice of therapies (Howes et al., 2018; Pilling, Baron-Cohen, Megnin-Viggars, Lee, & Guideline Development Group, 2012) as individual rather than group therapies tend to be more effective (Fusar-Poli et al., 2019).

Due to the high rates of comorbidity with other mental health disorders, it is important that mental health professionals consider the possibility of autism within adults who are referred to services. The identification of ASD is crucial not just for reaching the right diagnosis, but also for choosing the right course of treatment and support.

Improving recognition of the features of ASD or even actively screening for it within mental health patients would be beneficial to:

- Inform the environment and practitioner’s response to better accommodate the needs of those with autism

- Intervene to improve coping strategies based on autistic need

- Adapt treatment to ensure suitability with regards to autistic needs.

Improving recognition of the features of ASD helps services adapt their environment and treatment plans according to autistic need.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

#ElfNuggets

This blog was discussed by Becca Read in the October 2021 Elf Nuggets show, which you can watch here:

Links

Primary paper

Fusar-Poli L, Brondino N, Politi P, Aguglia E. (2020) Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. DOI: 10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w.

Other references

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

Baxter, A. J., Brugha, T. S., Erskine, H. E., Scheurer, R. W., Vos, T., & Scott, J. G. (2015). The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychological medicine, 45(3), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171400172X

Davidson, C., Greenwood, N., Stansfield, A., & Wright, S. (2014). Prevalence of Asperger syndrome among patients of an Early Intervention in Psychosis team. Early intervention in psychiatry, 8(2), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12039

De Cagna, F., Squillari, E., Rocchetti, M., & Fusar-Poli, L. (2019). Personality disorders and ASD. In: Keller R (ed) Psychopathology in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. pp 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26276 -1_10

Fusar-Poli, L., Brondino, N., Rocchetti, M., Petrosino, B., Arillotta, D., Damiani, S., Provenzani, U., Petrosino, C., Aguglia, E., & Politi, P. (2019). Prevalence and predictors of psychotropic medication use in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder in Italy: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry research, 276, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.013

Fusar-Poli, L., Ciancio, A., Gabbiadini, A., Meo, V., Patania, F., Rodolico, A., Saitta, G., Vozza, L., Petralia, A., Signorelli, M. S., & Aguglia, E. (2020). Self-Reported Autistic Traits Using the AQ: A Comparison between Individuals with ASD, Psychosis, and Non-Clinical Controls. Brain sciences, 10(5), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050291

Geurts, H. M., & Jansen, M. D. (2012). A retrospective chart study: the pathway to a diagnosis for adults referred for ASD assessment. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 16(3), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311421775

Giarelli, E., Wiggins, L. D., Rice, C. E., Levy, S. E., Kirby, R. S., Pinto-Martin, J., & Mandell, D. (2010). Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disability and health journal, 3(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

Happé, F. G., Mansour, H., Barrett, P., Brown, T., Abbott, P., & Charlton, R. A. (2016). Demographic and Cognitive Profile of Individuals Seeking a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adulthood. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 46(11), 3469–3480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2886-2

Hedley, D., Uljarević, M. (2018). Systematic review of suicide in autism spectrum disorder: current trends and implications. Current Developmental Disorder Reports 5:65–76

Hirvikoski, T., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Boman, M., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P., & Bölte, S. (2016). Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science, 208(3), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192

Hollocks, M. J., Lerh, J. W., Magiati, I., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Brugha, T. S. (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine, 49(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002283

Hossain, M. M., Khan, N., Sultana, A., Ma, P., McKyer, E., Ahmed, H. U., & Purohit, N. (2020). Prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among people with autism spectrum disorder: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry research, 287, 112922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112922

Howes, O. D., Rogdaki, M., Findon, J. L., Wichers, R. H., Charman, T., King, B. H., Loth, E., McAlonan, G. M., McCracken, J. T., Parr, J. R., Povey, C., Santosh, P., Wallace, S., Simonoff, E., & Murphy, D. G. (2018). Autism spectrum disorder: Consensus guidelines on assessment, treatment and research from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 32(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117741766

Hull, L., & Mandy, W. (2017). Protective effect or missed diagnosis? Females with autism spectrum disorder. Future Neurology, 12 (3) pp. 159-169. 10.2217/fnl-2017-0006.

Kenyon, S. (2014). Autism in pink: Qualitative research report. Retrieved from Autism In Pink Website. https://autisminpink.net.

Kerns, C. M., Rump, K., Worley, J., Kratz, H., McVey, A., Herrington, J., & Miller, J. (2016). The differential diagnosis of anxiety disorders in cognitively-able youth with autism. Cognitive Behaviour Practice 23(4) 530–547. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cbpra.2015.11.004

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Autism. Lancet (London, England), 383(9920), 896–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61539-1

Lai, M. C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. The lancet. Psychiatry, 2(11), 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

Lai, M. C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet. Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 24(5), 659–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172145

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule–2nd edition (ADOS-2). Western Psychological Corporation, Los Angeles, CA

Mandy, W., Chilvers, R., Chowdhury, U., Salter, G., Seigal, A., & Skuse, D. (2012). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 42(7), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1356-0

Nylander, L. (2014). Autism and schizophrenia in adults: clinical considerations on comorbidity and differential diagnosis comprehensive guide to autism. Springer, New York, pp 263–281.

Nylander, L., & Gillberg, C. (2001). Screening for autism spectrum disorders in adult psychiatric out-patients: a preliminary report. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 103(6), 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00175.x

Parish-Morris, J., Liberman, M. Y., Cieri, C., Herrington, J. D., Yerys, B. E., Bateman, L., Donaher, J., Ferguson, E., Pandey, J., & Schultz, R. T. (2017). Linguistic camouflage in girls with autism spectrum disorder. Molecular autism, 8, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0164-6

Paula-Pérez, I. (2013). Differential diagnosis between obsessive compulsive disorder and restrictive and repetitive behavioural patterns, activities and interests in autism spectrum disorders. Revista de psiquiatria y salud mental, 6(4), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2012.07.005

Pilling, S., Baron-Cohen, S., Megnin-Viggars, O., Lee, R., Taylor, C., & Guideline Development Group (2012). Recognition, referral, diagnosis, and management of adults with autism: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 344, e4082. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e4082

Rynkiewicz, A., Schuller, B., Marchi, E., Piana, S., Camurri, A., Lassalle, A., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2016). An investigation of the ‘female camouflage effect’ in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular autism, 7, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-016-0073-0

Smiley, K., Gerstein, B., Nelson, S. (2018). Unveiling the autism epidemic. Journal of Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience 2(2):1

Tromans, S., Chester, V., Kiani, R., Alexander, R., & Brugha, T. (2018). The Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Adult Psychiatric Inpatients: A Systematic Review. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health : CP & EMH, 14, 177–187. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901814010177

Wolf, J. M., & Ventola, P. (2014). Assessment and treatment planning in adults with autism spectrum disorders. In: Adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Springer, New York, USA. pp 283–298.

Wu, M. S., Rudy, B. M., & Storch, E. A. (2014). Obsessions, compulsions, and repetitive behavior: Autism and/or OCD. In T. E. Davis III, S. W. White, & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Autism and child psychopathology series. Handbook of autism and anxiety (p. 107–120). Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06796-4_8

Photo credits

- Photo by Chinh Le Duc on Unsplash

- Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

- Photo by Djim Loic on Unsplash

- Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

- Photo by Francesco La Corte on Unsplash

- Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash