Antipsychotic prescribing in people with learning disabilities is an important topic (McCloud, 2016). But what about those with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), with or without learning disabilities?

There is some evidence that antipsychotics, particularly atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone, help to reduce several behaviours associated with ASD, e.g. irritability, aggression, hyperactivity and self injury (Posey et al, 2008). A study of prescribing in primary care in the UK, showed that 29% of the children and young people with ASD were prescribed psychotropics, with antipsychotics being the third most frequently prescribed drugs (7.3%) (Murray et al, 2014).

However, in the UK, there is no licence for antipsychotic use in ASD and NICE guidance (NICE 2013) states:

Consider antipsychotic medication for managing behaviour that challenges in children and young people with autism when psychosocial or other interventions are insufficient or could not be delivered because of the severity of the behaviour.

The most recent Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines (Taylor et al, 2015) suggest that risperidone should be first line in this instance.

A new US authored meta-analysis by Su Young Park et al (2016) examines the antipsychotic prescribing in children and young people with ASD, and its publication coincides with the “Stopping Over-Medication of People with a Learning Disability” (STOMPLD) pledge, signed by many professional organisations in England in June this year.

The STOMPLD pledge was signed on 1st June 2016 by the Royal Colleges of Nursing, Psychiatrists and GPs, as well as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, the British Psychological Society and NHS England.

Methods

The authors “conducted a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis focusing on antipsychotic use in youth with ASD and/or learning disabilities to identify overarching trends across studies and to explore moderators of antipsychotic treatment”, which takes into account several individual studies of prescribing for this population.

The population was limited to children and young people up to 24 years of age diagnosed with ASD with or without a diagnosis of learning disabilities.

Primary outcomes

- The prevalence of ASD/learning disabilities diagnosis amongst youth treated with antipsychotics

- The prevalence of antipsychotic use in youth diagnosed with ASD/learning disabilities.

Secondary outcomes

- Antipsychotic treatment prevalence at different time intervals, and, in studies with longitudinal data, change in treated prevalence from baseline until last study time point.

Studies were included if:

- Sample size was ≥ 100 children or adolescents per study

- Population age was up to 24 years

- Reported quantitative data outlining frequency of those treated with antipsychotics as having ASD/learning disabilities.

Results

3,185 articles were initially identified. 89% of these were excluded from the study on the basis of title and abstract. 327 full text articles were then reviewed, leaving a total of 37 longitudinal and cross-sectional studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis. The total sample was 365,449 patients of whom 88,715 had a diagnosis of ASD with learning disabilities or learning disabilities alone (mean age 11.4 years).

Twenty-seven of these studies reported that n = 273,139 treated with antipsychotics also had ASD/learning disabilities. Thirteen studies reported that n=96,688 patients with on ASD/learning disabilities were treated with antipsychotics.

The majority of the studies came from the US, followed by Canada, Europe, New Zealand, Iran and Taiwan and were carried out in inpatient and outpatient settings.

Primary outcome

- Between 1 in 10 and 1 in 12 of children and young people treated with antipsychotics had a diagnosis of ASD/learning disabilities or ASD alone

- 1 in 6 children and adolescents with ASD received antipsychotics.

Secondary outcome

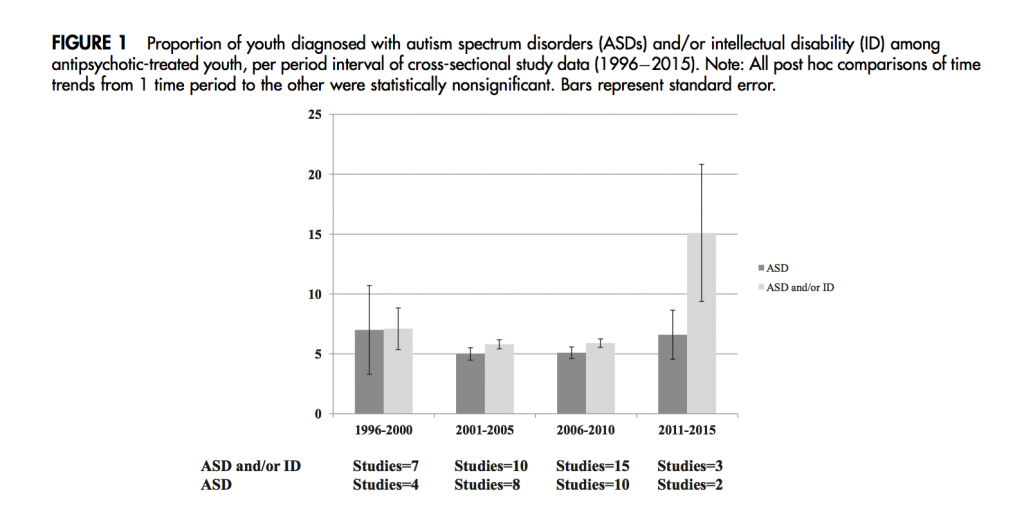

- Longitudinal studies showed that the proportion of young people with an ASD/learning disabilities diagnosis amongst those treated with an antipsychotic did not fluctuate significantly over time; ranging from 7.3% to 6.4% (OR= 1.0; 95% CI =0.9 to 1.1, p =.78).

- Cross sectional studies show doubling in proportion of young people treated with antipsychotics with a diagnosis ASD/learning disabilities from 7.1% in 1996 to 15.1% in 2011 (see figure 1).

Conclusions

- A substantial proportion of young people up to age 24 years who are treated with antipsychotics have a diagnosis of ASD and/or learning disabilities

- 16% of young people with a diagnosis of ASD are treated with an antipsychotic

- The proportion of those treated with an antipsychotic and having ASD/learning disabilities has not changed significantly in the last 20 years.

Strengths and limitations

This meta-analysis gives strong evidence of the prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing in predominantly American children and young people. Combining data from many studies helps to draw stronger conclusions than would be possible from individual studies.

It is of interest that the publication of the RUPP study (McCraken et al, 2002) which showed that risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, is effective in children with ASD was associated with increases in the use of antipsychotics in subsequent years. Sample size and more recent year of publication were predictors of higher prevalence of ASD/learning disabilities diagnoses. The increase is highlighted further without statistical verification; the reality being that the increase is shown in a small number of studies in the later time period which is a long time post 2002.

We found the reporting of the findings somewhat confusing, particularly the amalgamation of ASD and learning disabilities diagnoses, and only in certain instances are these further separated out. We assume that the small numbers of papers found for the meta-analysis was the reason for not making this further distinction or exclusion.

The majority of studies were of American origin (64%) and therefore, the increase of antipsychotic prescribing over time is not surprising, given that the Food and Drug Administration approved risperidone (2006) and later aripiprazole (2009) for the treatment of challenging behaviour in children and young people with ASD with/without learning disabilities. We believe that this is a more explicit policy than the lack of specific prescribing guidance in other countries where antipsychotics are also frequently used in this population.

Summary

The paper gives clear indication of increase in ASD/learning disabilities diagnoses among those treated with antipsychotics, but also an increase in antipsychotic prescribing in those diagnosed with ASD alone. These findings confirm prescribing trends shown in individual studies internationally and illustrate the constant tensions in managing challenging behaviour in clinical practice without resorting to pharmacological interventions.

This evidence points to substantial over-treatment of young people using antipsychotic medication.

Links

Primary paper

Park SY, Cervesi C, Galling B, Molteni S, Walyzada F, Ameis SH, Gerhard T, Olfson M, Correll CU. (2016) Antipsychotic Use Trends in Youth With Autism Spectrum Disorder and/or Intellectual Disability: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Volume 55, Issue 6, Pages 456-468.e4, ISSN 0890-8567, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.03.012

Other references

McCracken J, McGough J, Shah B et al. (2002) Risperidone in Children with Autism and Serious Behavioral Problems. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:314-321 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa013171.

McCloud T. (2016) Antipsychotic overprescribing in people with learning disabilities #UCLJournalClub. The Learning Disabilities Elf, 15 Jun 2016.

Murray ML, Hsia Y, Glaser K, Simonoff E, Murphy DGM. Asherson PJ, Wong ICK. (2014) Pharmacological treatments prescribed to people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in primary health care. Psychopharmacology, 231(6), 1011–1021. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-013-3140-7

NICE (2013) Autism in under 19s: support and management. NICE CG 170 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170

Posey DJ, Stigler CA, Erickson CA, McDougle CJ. (2008) Antipsychotics in the treatment of autism. J Clin Invest. 118(1):6-14. doi:10.1172/JCI32483

Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S. (2015) Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (The Maudsley). 12th Edition. Wiley Blackwell

Doctors urged to help stop ‘chemical restraint’ as leading health professionals sign joint pledge. NHS England, 1 Jun 2016.

Photo credits

Trends in antipsychotic prescribing in autism

USA https://t.co/NGJ9umG3FZ

Blog by @likahassiotis & James Dove @CI_NHS @PBSstudy @LearningDisElf @UCLPsychiatry https://t.co/v8Biiu6o8u

New evidence of substantial over-treatment of young people with #autism using antipsychotic drugs https://t.co/xLe3C3bsk8

NEW BLOG @likahassiotis Trends in #antipsychotic prescribing in #autism https://t.co/xLe3C3bsk8 #evidencelive @AllenFrancesMD @PaulGlasziou

Trends in #antipsychotic prescribing in #autism https://t.co/P7DuFUk4L5 @LearningDisElf

RT @LearningDisElf:New evidence of substantial over-treatment of young people with #autism using antipsychotic drugs https://t.co/jJLpVDE3gC

Trends in antipsychotic prescribing in autism https://t.co/9BYb7ngHew via @LearningDisElf

[…] Trends in antipsychotic prescribing in autism […]