Our conference today at the Royal Society of Medicine brings together professionals and service user representatives to discuss current issues in the use of psychotropic medication for people with intellectual disability.

In this blog post we recap some history, review current policy, and reflect on the challenges in improving psychotropic medication use in people with intellectual disability.

The historical context: overprescribing of antipsychotic medication

Concern about the use of psychotropic medication is not new; it is possible to find authors over 30 years ago questioning the high proportion of people with intellectual disability receiving these drugs (Aman & Singh, 1983; Bates et al, 1986). The main anxiety is that people with intellectual disability are receiving psychotropic medication when they do not have a mental illness. Particular focus has fallen onto the antipsychotics as the most frequently prescribed type of psychotropic in this group, and their use to manage ‘challenging behaviour’. This use is problematic for several reasons:

- The lack of good quality evidence to support the efficacy of antipsychotics in reducing challenging behaviour

- The potentially-serious side-effects

- The opportunity cost of using medication in preference to psychosocial and environmental interventions that may target the cause of the behaviour and improve quality of life

- The complexities of psychotropic prescribing are compounded in people with intellectual disability who appear to be more sensitive to unwanted effects and who might lack capacity to consent to treatment.

With the closure of the large institutions for people with intellectual disability and the move to independent or supported community living came the expectation of generally lower rates of psychotropic prescribing. This hope was not realised, and people moving from hospitals into the community remained a highly medicated group (Thinn et al, 1990).

The debate around psychotropic medication use was reignited by the exposure of abuse at Winterbourne View Hospital in 2011. Transforming Care, the Government response to the scandal, took a broad view of the care offered to people with intellectual disability and complex needs, and concluded that major changes were urgently needed (Department of Health, 2012). The authors of Transforming Care highlighted ongoing concern about the inappropriate use of psychotropic medication, although at the time there was no substantive evidence on which to base the widely-held belief that psychotropic medication was being over-used.

This changed in 2015 when two large pharmaco-epidemiological studies, including our own, highlighted the extent of contemporary psychotropic prescribing to people with intellectual disability in primary care (Sheehan et al, 2015; Public Health England, 2015). Both studies demonstrated a striking disparity between rates of psychotropic prescription and recording of underlying mental illness for which they are indicated. The work gained widespread media attention and we heard moving personal accounts from relatives and carers that affirmed the need for improvements in care for people with intellectual disability, including better use of psychotropic medication. NHS England soon issued a ‘Call to Action’ and the STOMP (Stopping Over-Medication of People with learning disabilities) programme was born.

Psychotropic medications have been over-used in people with intellectual disability.

The policy: STOMP programme

The STOMP programme brings together a series of interventions and initiatives aimed at providers and commissioners of services and uses ‘nudge’ tactics to change prescribing behaviour. Awareness of the programme has steadily built and we have heard many informal reports of local successes in small-scale projects. Whether these will translate to national reductions in psychotropic prescribing, however, remains to be seen. Public Health England will monitor this using routinely-collected health data to build a longitudinal picture of psychotropic prescribing. The possibility of more assertive regulation of prescribing, for example, by the Care Quality Commission, remains an option.

There are obvious parallels between the STOMP project and that National Dementia Strategy published in 2009, a key objective of which was to reduce inappropriate antipsychotic prescribing for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012). This project resulted in a halving of the number of people with dementia receiving antipsychotic medications by 2011. The STOMP programme hopes for similar impact, although specific targets for reducing psychotropic medication prescriptions have not been set.

It might be that a focus purely on medication reduction is too narrow and denies the benefit that some people with intellectual disability undoubtedly derive from psychotropic medication. We advocate rational, rather than rationed, prescribing of these medications and prefer the term ‘medication optimisation’ to reflect the broader context in which prescribing decisions are made. Optimisation implies a more nuanced approached to prescribing, allowing flexibility in reaching collaborative treatment decisions and the inclusion of medication within individualised care plans.

The STOMP project is a national drive to reduce antipsychotic prescribing for people with intellectual disability.

The challenges

But there is still some way to go. Anecdotal evidence, and a limited research literature, indicates that people with intellectual disability and their carers frequently feel excluded from psychotropic medication decisions, deprived of options, and can find it difficult to ask for more information or to challenge decisions (Lalor & Poulson, 2013). We need new and effective ways to monitor the effect of psychotropic medication and involve people with intellectual disability and their carers in medication discussions.

Clinical experience tells us that reducing psychotropic medication is not always straightforward. Some people are understandably reluctant to consider changes to medication regimes that might have been unchanged for years and where it has become difficult to judge the (positive or negative) impact of treatment. General practitioners may feel ill-equipped to initiate medication changes and specialist psychiatrists might be difficult to access. In some cases, knowledge of the original indication for medication has been lost, particularly where people have moved between care settings, transitioned from child to adult services, or returned from out-of-area specialist placements. Many people seem to have little faith in crisis support or respite services being able to help should things get worse. Such uncertainty contributes to a ‘status quo’ bias and it is easy to see why people with intellectual disability who are prescribed psychotropic medications tend to receive them for a long time.

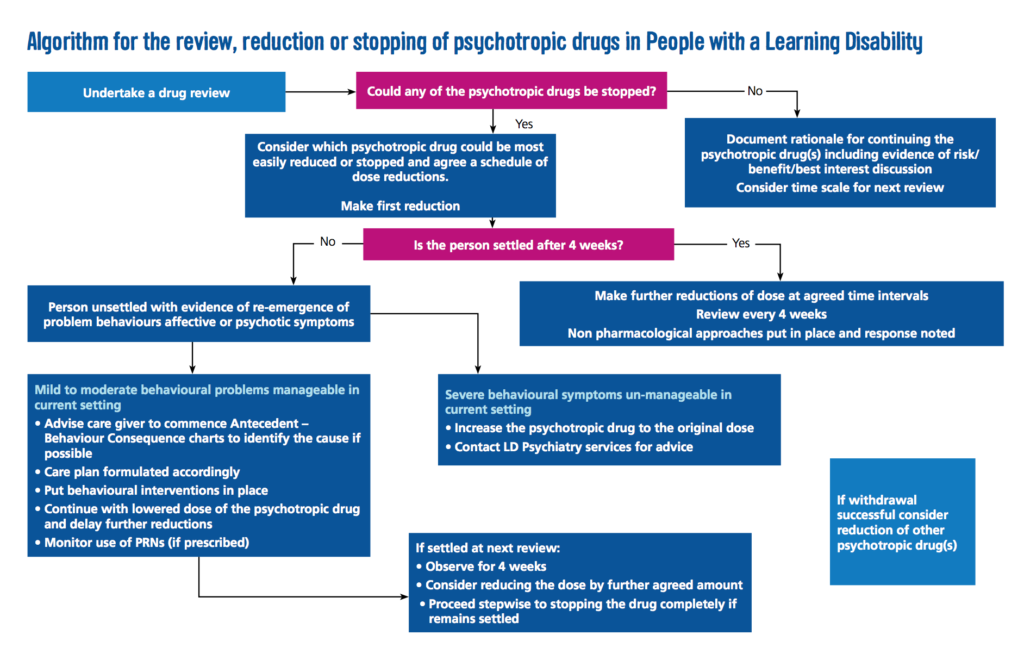

We recently reviewed the literature concerning the effect of reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotic medication used for challenging behaviour. While a significant proportion of people could have their antipsychotic medication reduced or even stopped, a roughly equal number suffered an array of adverse effects (Sheehan & Hassiotis, 2017). In some cases this required medication to be re-prescribed at higher doses. The overall quality of included studies was poor, however, and data were not sufficient for us to confidently identify predictors of successful antipsychotic medication reduction. Decisions to reduce or stop psychotropic medication must therefore be taken on an individual basis.

Of course improving psychotropic medication use does not begin and end with prescribers. Equally important is the availability and effectiveness of alternative, pro-active interventions for complex presentations and the provision of good quality care and support. Studies have shown up to a four-fold difference in rates of antipsychotic prescribing for challenging behaviour between people with different living environments, despite there being no significant difference in the prevalence of behaviour disorder (Clarke et al, 1990). We are pleased that the STOMP pledge now extends to the social care sector and encouraged by the support already committed.

Optimising psychotropic medication requires the concerted action of health and social care services.

The future

Meaningful and sustained shifts in prescribing practice cannot occur without systems change and investment. The additional funding envisaged from the further closure of specialist inpatient beds for people with intellectual disability seems to have largely failed to reach front-line services (Taylor et al, 2016). Together with changes to welfare benefits, too many people with intellectual disability still find themselves lacking the right support and opportunities (Mason, 2017).

We need to find practical ways of improving the lives of adults with intellectual disability and complex additional needs. Psychotropic medication is only one piece of the jigsaw and cannot be seen in isolation. The care for people with intellectual disability is rightly high on the agenda of NHS England; progress is indeed possible, but rhetoric must be matched by action.

You can follow the conference today on Twitter at #RSMpsychotropics. Dr Rory Sheehan @dr_rorysheehan and Professor Angela Hassiotis @likahassiotis will be available online to respond to your comments and questions.

You can follow the conference today on Twitter at #RSMpsychotropics

Links

Aman M & Singh NN. (1983) Pharmacological intervention. Handbook of Mental Retardation. New York: Pergamon.

Bates WJ, Smeltzer DJ & Arnoczky SM. (1986) Appropriate and inappropriate use of psychotherapeutic medications for institutionalized mentally retarded persons. Am J Ment Defic 1986 90(4) 363-370. [PubMed abstract]

Clarke DJ, Kelley S, Thinn K & Corbett J. (1990) Psychotropic drugs and mental retardation: 1. Disabilities and the prescription of drugs for behaviour and for epilepsy in three residential settings. J Intellect Disabil Res 1990 34(5) 385-395. [PubMed abstract]

Department of Health (2012) Transforming Care: A national response to Winterbourne View Hospital (PDF). London, UK.

Health and Social Care Inormation Centre (2012) National Dementia and Antipsychotic Prescribing Audit (PDF). Leeds, UK.

Lalor J & Poulson L. (2013) Psychotropic medications and adults with intellectual disabilities: care staff perspectives. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities 2013 7(6) 333-345. [Abstract]

Mason R. ‘I’m angry’: voter confronts Theresa May over disability benefit cuts. The Guardian 15 May 2017. (accessed 18 May 2017)

Public Health England 2015. Prescribing of psychotropic drugs to people with learning disabilities and/or autism by general practitioners in England (PDF). Public Health England. London, UK.

Sheehan R & Hassiotis A. (2017) Reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotics for challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2017 4(3) 238-256. [PubMed abstract]

Sheehan R, Hassiotis A, Walters K, et al. (2015) Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. BMJ 351 h4326.

Taylor JL, McKinnon I, Thorpe I & Gillmer BT (2016) The impact of transforming care on the care and safety of patients with intellectual disabilities and forensic needs (PDF). BJPsych Bulletin 2016 41(2) 1-4.

Thinn K, Clarke DJ & Corbett J. (1990) Psychotropic drugs and mental retardation: 2. A comparison of psychoactive drug use before and after discharge from hospital to community. J Intellect Disabil Res 1990 34(5) 397-407. [PubMed abstract]

An extremely useful article particularly for a general adult Psychiatrist.