We have something a bit different for you today. It’s the text of a talk I gave at the #MindTech2016 conference in London this lunchtime. I was on the panel for the debate, which tackled this question:

This house believes self-guided computerised CBT (cCBT) no longer has a place in the evidence-based management of depression.

My thanks to the #MindTech2016 organisers for inviting me to participate in this discussion, which we covered as part of our new #BeyondTheRoom digital conference service. The debate was chaired by Professor Richard Morriss from the University of Nottingham and my fellow panellists were:

- Dr Kate Cavanagh, Senior Lecturer in Clinical Psychology, University of Sussex

- Dr Stefan Rennick-Egglestone, Digital Research Specialist, University of Nottingham

- Melissa Briscoe, Head of Psychological Therapies, Self Help Services, Manchester

- André Tomlin, The Mental Elf

My talk

Good afternoon fellow MindTechies. I hope you’re having fun at #MindTech2016 so far! Vanessa, Mark and I are really enjoying covering it with our new #BeyondTheRoom service and we look forward to speaking with as many of you as possible during the day.

My Mental Elf Twitter poll on this question will be ending soon and the result has been resoundingly FOR the motion. Over two thirds of the people who voted, agree that self-guided cCBT has no place in the evidence-based management of depression.

My own lived experience

Living with depression is tough. I have personal experience of this illness, having been through a year long episode that lifted quite recently. I was prescribed antidepressants first by my GP, then counselling by my local psychotherapy service. I also used exercise, mindfulness and computerised CBT off my own bat.

None of these interventions were perfect for me, but in combination and with lots of support from my family I got my head back above water. It’s hard for me to say for sure which of these treatments was most effective, but I certainly felt like the cCBT was the least useful. I found it slow and boring and I quickly lost interest. So speaking personally, I would also be FOR the motion.

cCBT didn’t help me personally, but that’s not to say it wouldn’t help others.

So what does the evidence tell us about self-guided cCBT for depression?

As the man behind the Mental Elf website, I spend most of my waking hours reading mental health research, so I should be in a good position to provide a succinct summary.

NICE like cCBT

Well, NICE recommends cCBT for depression in adults. So, what do you say, shall we just leave it there and pack up for an early lunch?

Bias in psychotherapy research

As is often the case in psychotherapy research, most trials have been conducted by enthusiasts (i.e. the people who developed the online programmes who clearly have significant vested interests). The trials often include rather atypical populations and so the application of their results in the real-world can be troublesome.

REEACT trial finds no benefit and low uptake of cCBT in adults

The REEACT randomised controlled trial led by Simon Gilbody from York University and published in the BMJ just over a year ago, was the first large scale primary care study in this field, which makes it a really good test of self-guided cCBT. They reported very low uptake and no benefits of cCBT over usual care.

BUT, IPD meta-analysis shows small but significant effect

However, an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis with almost 4,000 participants by Pim Cuijpers from the VU University in Amsterdam, which includes the REEACT trial plus 12 other major studies in this area, finds a small but significant effect of cCBT vs untreated controls. So for me the questions is, are these small effects clinically relevant and in what setting?

I think it’s relevant here to draw on the Internet-based smoking cessation research led by Ricardo Munoz from Palo Alto University in California, which has shown that if online programmes are disseminated worldwide, although the treatment effects on an individual may be small, the overall impact on a population can be huge. I can certainly see a place for computerised CBT being rolled out in low and middle income countries where there is little or no mental health system for people with depression.

The biggest meta-analysis to date shows that cCBT has a small but significant effect on adult depression.

Doing it for the kids?

It’s also worth noting that trials evaluating the effectiveness of cCBT for depression and anxiety in young people have reported more positive results. Like REEACT, some of these studies suffer from low levels of engagement, but others don’t. For example, we blogged about an RCT of the Stressbusters programme, led by Patrick Smith from King’s College London and published last year in Behaviour Research and Therapy, which reported an 86% adherence rate after 8 sessions. Perhaps adherence is better in young people who are digital natives?

Only half of psychotherapy trials measure harm

Safety is also an issue. We know that only half of psychotherapy trials measure and report on the side effects of treatment, compared to 100% of drug trials in psychiatry. People say that talking treatments are unlikely to cause harm, but any treatment that’s powerful enough to have a positive effect is also going to have negative consequences for some patients.

Attrition bias and the importance of follow-up

Attrition rates are a big problem in digital mental health trials and quite frankly I’ve become bored of reading the excuses. Time and time again I see researchers saying that less than 20% of participants completed the treatment, but that this is typical of web-based therapies, so it’s something we have to live with. It’s not.

The drop out rate in digital mental health trials is often huge, which seriously biases the results.

Trying to fit an RCT into a digital innovation shaped hole

And of course, researchers are still playing catch up with digital innovation. The REEACT study published in November 2015 was originally registered in 2007, when the technology landscape was quite different. Some of you may remember that’s when Apple launched a new phone that’s become quite popular. The two cCBT programmes investigated in the REEACT study (Moodgym and Beating the Blues) are hardly what we would consider exciting digital innovation in 2016. We need faster, more reactive, more flexible study designs and data systems such as those being developed by Byron George and his PC-MIS team at the University of York.

So, am I FOR or AGAINST the motion?

It’s a hard motion to support unequivocally, but that’s what the debate organisers have asked me to do!

cCBT is definitely not for me personally, but I do still see a place for it, particularly in settings with limited access to good alternative treatments for depression. However, if we are to roll-out cCBT at a population level, we first need to work out what specific elements of cCBT interventions increase efficacy and engagement.

I guess overall I’m more FOR the motion than AGAINST it. Thanks for listening!

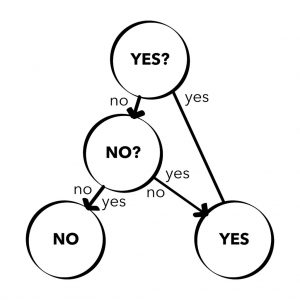

MindTech debates: rarely a simple decision.

Links

Computerised CBT for depression is no better than usual GP care: the REEACT trial

Psychotherapy trials should report the side effects of treatment