Mental health can affect women at any point during their pregnancy, including problems such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders, postpartum psychosis and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The ‘baby blues’ is estimated to affect around 80% of new mothers up to 2 weeks after birth. Postnatal depression (PND) on the other hand is more severe and can last up to a year, with symptoms including problems bonding with one’s baby, inability to cope, fatigue, withdrawal, and insomnia. PND can be due to a range of factors, related to previous mental health, social support, stressful life events, past trauma, and biological changes during pregnancy (for more info check out MIND). PND also affects an infant’s cognitive and behavioural development.

Approximately 10-15% of new mothers are affected by PND. However, prevalence rates do vary across sources, and may be higher than this, especially in low-middle income countries. In 2011, the NHS highlighted that rates in the UK are likely higher, based on a survey where 26-33% of 2,318 mothers reported suffering from PND. PND also affects fathers and partners too.

The NHS offers two treatments; antidepressants that can have adverse effects and psychological therapies, which can have long waiting lists (and sometimes side effects too). Also recommended is self-help; highlighting the need to consider alternative options.

In light of this, Fancourt & Perkins (2018) conducted the first known randomised controlled trial (RCT) on singing as a psychosocial intervention for PND. Singing has been shown in RCTs to benefit older adults (Coulton, 2015) and also those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Lord, 2012).

Singing workshops with mothers and their babies.

Methods

Adult women up to 40-weeks post-birth with an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Score (EPDS) of ≥10 (indicating PND) were randomised to a singing group, a creative play group or a usual care control. Randomisation was clearly described, although researchers and participants were not blinded.

The singing and play groups received 60-minute workshops for 10 weeks in groups of 8-12 with mothers and their infants. Singing involved learning songs and singing to babies, listening to leaders perform songs, and creating new songs. Creative play included arts and crafts, playing games, and mother-infant sensory play. Both groups were led by the same leaders to ensure consistency. Mothers in the wait-list control completed singing groups after the study as a thank you.

Two-way repeated Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) measures assessed EPDS across time and the time by group interactions. Planned sensitivity analyses were conducted to look at the difference in women with an EPDS ≥10 and with an EPDS ≥13 (indicating moderate-severe PND). In total, 134 women provided data across baseline, week 6 and week 10 (91% completion rate from enrolment).

Results

Demographic data was statistically well-matched at baseline across all groups (see table 1 in the paper).

EPDS scores for all three groups significantly decreased across time, demonstrating PND improved across 10 weeks in singing, creative play and usual care (Table 2 shows raw EPDS scores).

Table 2: Mean EPDS score across time in the three groups

| EPDS≥10 μ ± SE (CI) | |||

| Singing | Play | Control | |

| Baseline | 13.85 ± 0.44 (12.98-14.73) | 13.83 ± 0.47 (12.90-14.77) | 13.05 ± 0.46 (12.14-13.97) |

| Week 6 | 9.46 ± 0.61 (8.25-10.67) | 10.86 ± 0.65 (9.56-12.15) | 10.18 ± 0.64 (8.92-11.45) |

| Week 10 | 8.67 ± 0.41 (7.86-9.48) | 9.05 ± 0.44 (8.18-9.91) | 8.80 ± 0.43 (7.95-9.64) |

| EPDS≥13 μ ± SE (CI) | |||

| Singing | Play | Control | |

| Baseline | 15.73 ± 0.44 (14.86-16.61) | 16.00 ± 0.50 (15.00-17.00) | 15.46 ± 0.51 (14.44-16.47) |

| Week 6 | 10.27 ± 0.79 (8.70-11.83) | 12.57 ± 0.90 (10.78-14.35) | 12.82 ± 0.92 (11.00-14.65) |

| Week 10 | 9.40 ± 0.55 (8.31-10.49) | 9.96 ± 0.62 (8.71-11.20) | 9.73 ± 0.64 (8.46-11.00) |

Notes: μ = mean; SE = standard error; CI = 95% confidence intervals

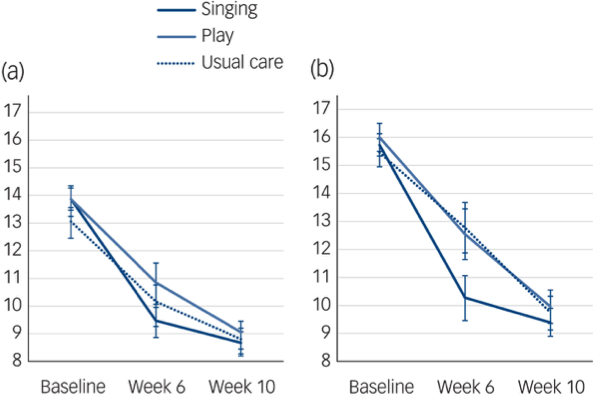

Regarding time by group interactions, there was no significant effect using EPDS ≥10. With EPDS ≥13, this time by group interaction was significant. Within-participant contrasts found a significant difference between groups from baseline to week 6, but not from week 6 to week 10. Post hoc tests found that the singing group had a significantly faster improvement from baseline to week 6 compared to the control group, but not compared with the play group, and with no difference between the play or control group, see Figure 1.

Figure 1 Changes in PND from baseline to week 10. (a) EPDS ≥ 10 and (b) EPDS ≥ 13 with standard error in singing, play and usual care groups.

Sensitivity analyses of whether mothers were receiving additional treatment for their mental health did not affect the significance of results across time or for the time by group interactions.

Results demonstrated that mothers with moderate-severe PND had a faster improvement in their symptoms in the singing group compared to usual care, with this boost in recovery shown statistically across the first 6 weeks, and narrowing again by week 10.

Mothers with moderate-severe PND had a significantly faster improvement in their symptoms in the singing group compared to usual care.

Conclusions

The result of all three groups having lower PND symptoms across the 10 weeks was in line with research showing that symptoms generally improve over time. However, the result that PND symptoms improved significantly faster in the singing group compared to usual care, suggests that singing could be a clinically relevant intervention for PND, as quicker recovery is associated with better outcomes for mother and baby.

The authors acknowledge that there were no significant differences between the speeds of recovery in singing or creative play, possibly as both share social elements. Although why there was no difference between play and controls needs further exploration (see next section). Overall, no negative effects or adverse events were reported across the study.

Future work should replicate with a larger sample in order to verify singing interventions for use in clinical practice.

Future work should replicate with a larger sample in order to verify singing interventions for use in clinical practice.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first known RCT on singing and postnatal depression (PND). Overall this study provides promising evidence for the use of singing workshops for mothers with moderate-severe PND using a robust design and a validated screening tool. The results support wider RCTs on listening to music reducing stress and anxiety in pregnancy (Hepp P. et al, 2018; García González J. et al, 2018).

Singing is a complex arts intervention that impacts us across many individual, social and community levels (Fancourt, 2017). Therefore understanding mechanisms behind interventions is important e.g. why did creative play not have the same speed of recovery as singing? The authors additionally conducted a qualitative study of the RCT to explore this (Perkins, 2018). Future RCTs should also incorporate mixed-methods, as well as looking at other group activities. Replication of complex arts interventions can also be an issue if thorough descriptions are not included, this can be found for this study in Fancourt & Perkins (2019).

Quicker improvements in women with moderate-severe PND were seen in the singing group across the first six weeks compared to usual care, however this was not seen after creative play. Research on social bonding has mirrored this speed of recovery. Coined the ‘ice-breaker effect’, a study by Peace et al, (2015) found group singing sped up social bonding faster than other social activities (crafts and creative writing), as shown significantly in the first initial month. At month 3 and month 7, however, the differences in bonding between the singing and non-singing groups were no longer significant, although all had increased bonding over time. Theories of singing as an evolutionary social tool for facilitating group and mother-infant bonding may be a key element of the faster initial benefits reported in these studies.

Singing research can be criticised if participants self-select themselves, and therefore benefits seen in studies may be exaggerated if only participants that already enjoy singing are taking part. Participants may have enrolled in this RCT due to the chance of joining a singing group. However, at baseline, there were no differences between groups in how much they already sang to their baby, so the singing group did not engage more with singing than the play or control groups before the intervention.

Whether women had any other mental health problems, as well as barriers to engagement such as ethnicity would have been of interest. As research has reported negative associations and barriers to singing felt initially in singing research (Warran et al, 2019). Future work should include cost evaluation, and consider fathers and partners too. Overall, this RCT suggests that group singing is a promising psychosocial intervention for mothers with PND.

‘Melodies for Mums’ illustration by Claire M (project participant), 2018

Implications for practice

Breathe Arts Health Research have directly translated this research into practice! Melodies for Mums (Southwark, London), provides weekly singing sessions over 10 weeks for mothers with PND, following the workshop design used in the RCT. The research gives credibility to the programme, which is important for communicating with the clinical sector, and for funders.

Songs are culturally diverse, multilingual and the programme is free making it inclusive and accessible to many local mothers. However, barriers include how close women are to the location and not having additional sibling childcare. Mainly women self-refer after hearing about the programme from the Breathe team at clinics, but women are also referred by health and community teams. Women who have either not accessed or not wanted to follow up on other support options have been successfully reached, and then also signposted to other services.

This is a brilliant example of research impacting directly to real-world practice. It would be fantastic to see more services like this across the UK. In the future I hope to see singing groups recommended as a treatment option for women and partners with PND.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you to Tim Osborne and Rosie Dow from Breathe Arts Health Research, who provided me with the information about Melodies for Mums.

#LetsTalkMentalHealthII videos

#LetsTalkMentalHealthII is a series of videos created by the ESRC Mental Health Leadership Fellow (Prof Louise Arseneault) and her team, which aims to:

- Look ahead to the future for young people in mental health

- Highlight young people’s voice in mental health

- Promote the work of emerging disciplines in mental health

- Emphasise the perspectives of people with lived experience of mental health difficulties.

Join the #LetsTalkMentalHealthII conversation on Twitter or watch the videos on the Mental Health Leadership YouTube channel.

Conflicts of interest

Saoirse has worked with both Daisy Fancourt and Rosie Perkins, and continues to work with Daisy on arts and health projects. Saoirse voluntarily collected data on a separate study on singing and PND for both authors, as part of her Master’s thesis. Although Saoirse had no input on any analysis or publication, she was thanked for data collection in the acknowledgements. However, she had no association with this RCT.

Primary paper

Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2018). Effect of singing interventions on symptoms of postnatal depression: three-arm randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(2), 119-121.

Other references

Coulton, S., Clift, S., Skingley, A., & Rodriguez, J. (2015). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community singing on mental health-related quality of life of older people: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(3), 250-255.

Fancourt D. Arts in Health: Designing and researching interventions. Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press, 2017 [Abstract]

Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2019). Creative interventions for symptoms of postnatal depression: a process evaluation of implementation. Arts & Health, 11(1), 38-53. [Abstract]

García González, J., Ventura Miranda, M. I., Requena Mullor, M., Parron Carreño, T., & Alarcón Rodriguez, R. (2018). Effects of prenatal music stimulation on state/trait anxiety in full-term pregnancy and its influence on childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 31(8), 1058-1065. [Abstract]

Graham S & Burgess J. Persistent and severe postnatal depression predicts adverse outcomes in children. The Mental Elf, 14 June 2018.

Hepp, P., Hagenbeck, C., Gilles, J., Wolf, O. T., Goertz, W., Janni, W., … & Schaal, N. K. (2018). Effects of music intervention during caesarean delivery on anxiety and stress of the mother a controlled, randomised study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 18(1), 435.

Lord, V. M., Hume, V. J., Kelly, J. L., Cave, P., Silver, J., Waldman, M., … & Man, W. D. (2012). Singing classes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, 12(1), 69.

MIND. Understanding postnatal depression. MIND, 2016.

Molyneaux E. Over 1 in 10 women have depression during pregnancy or postnatally #HopeNov20. The Mental Elf, 20 November 2017.

Pearce, E., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. (2015). The ice-breaker effect: singing mediates fast social bonding. Royal Society Open Science, 2(10), 150221.

Perkins, R., Yorke, S., & Fancourt, D. (2018). How group singing facilitates recovery from the symptoms of postnatal depression: a comparative qualitative study. BMC psychology, 6(1), 41.

Tomlin A. Should we screen new Dads for depression? #DadsMHday. The Mental Elf, 18 June 2018.

Warran, K., Fancourt, D., & Wiseman, T. (2019). How does the process of group singing impact on people affected by cancer? A grounded theory study. BMJ open, 9(1), e023261.

Additional PND papers by the authors

Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2019). Does attending community music interventions lead to changes in wider musical behaviours? The effect of mother–infant singing classes on musical behaviours amongst mothers with symptoms of postnatal depression. Psychology of Music, 47(1), 132-143. [Abstract]

Fancourt D, Perkins R. The effects of mother–infant singing on emotional closeness, affect, anxiety, and stress hormones. Music & Science, 2018, 1:2059204317745746.

Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2018). Could listening to music during pregnancy be protective against postnatal depression and poor wellbeing post birth? Longitudinal associations from a preliminary prospective cohort study. BMJ open, 8(7), e021251.

Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2018). Maternal engagement with music up to nine months post-birth: Findings from a cross-sectional study in England. Psychology of Music, 46(2), 238-251. [Abstract]

Perkins, R., Yorke, S., & Fancourt, D. (2018). Learning to facilitate arts-in-health programmes: A case study of musicians facilitating creative interventions for mothers with symptoms of postnatal depression. International Journal of Music Education, 36(4), 644-658. [Abstract]

Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2017). Associations between singing to babies and symptoms of postnatal depression, wellbeing, self-esteem and mother-infant bond. Public health, 145, 149-152. [Abstract]

Photo credits

- Video still by Breathe Arts Health Research from Melodies to Mums

- Photo by Leigha Fearon from Melodies to Mums

- Drawing byMelodies to Mums participant Claire M 2018