LGBTQ+ youth face a greater mental health burden than heterosexual peers, with higher rates of depression, suicidality, and other symptoms of poor mental health (Amos et al., 2020; Semlyen et al., 2016).

At the same time, the uptake of mental health support among LGBTQ+ young people is less than among heterosexual youth (McDermott, 2015). The disparity in seeking support can include fears of being judged, cis-heteronormativity, limited awareness of LGBTQ+ issues, or excluding youth from their care decisions (McDermott et al., 2018). Although research has attempted to capture the barriers limiting engagement and access to mental health services (Wilson & Cariola, 2020), it has not yet explored any facilitators to encourage engagement or the impact of intersectional factors.

This meta-narrative review by McDermott and colleagues (2021) puts together empirical and theoretical evidence intending to develop a theoretical understanding of how early intervention mental health services can support LGBTQ+ youth with common mental health problems.

Exploring how mental health services work and the experiences of young LGBTQ+ service users can contribute to the development of inclusive healthcare.

Methods

This study was a meta-narrative review. The researchers searched an array of databases for literature, including Medline, CINAHL, PsychINFO and Academic Search Ultimate.

For studies to be included in the review, the participants needed to be from the LGBTQ+ community, aged under 26 years and were being provided interventions to support their mental wellbeing. Furthermore, the studies had to be published after 1990, written in either English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French and in a peer-reviewed journal. If the research focused on crisis care and inpatient services, it was not included in the review.

Data on the setting in which the research took place, findings, study design, theoretical perspective and intervention/service were extracted. In addition, the researchers created a tool to examine the quality of the studies, which was adapted from the EPPI-Centre ‘Weight of Evidence Framework’ (Gough, 2007) and recommendations for theory-led systematic reviews (Jagosh et al., 2011).

Results

2,951 studies were screened for eligibility, and 88 met the inclusion criteria. The researchers conceptualised the literature into three meta-narratives: psychology, psychosocial and social/youth work.

Psychology

- Within this body of knowledge, the interventions used were typically individual-led, for example, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

- There was little to no focus on the broader socio-cultural context that could be contributing to mental distress among LGBTQ+ youth.

Psychosocial

- This meta-narrative considers the role of both the individual and the social context in which mental distress is maintained. Therefore, these interventions recognised the importance of intersectionality and included social components (i.e., school belonging).

- They also delivered them in the community, for example, in youth health centres or school settings.

Social/youth work

- This component recognises individuals’ wider communities and resources that may be contributing to mental distress.

- The interventions were based on societal factors, and were based in the community (i.e., school settings and youth organisations).

Theoretical framework to provide effective mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth

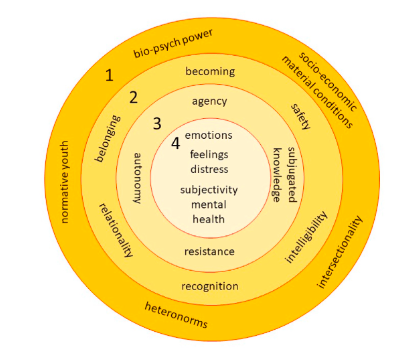

After the researchers derived these three meta-narratives, they developed a multi-layered theoretical framework that contains the critical components to providing adequate early intervention mental health support to LGBTQ+ youth:

The framework suggests that various individual-level and societal structures should be addressed when supporting LGBTQ+ youth’s mental wellbeing.

(1) Macro outer ring 1

- The outer ring represents how institutions, laws, and people influence the ways LGBTQ+ youth view themselves, whether they will access mental health services and how they socialise with others.

- Furthermore, it is important to recognise how heteronormative codes within society play a massive role in the marginalisation, silence, and invisibility of LGBTQ+ youth.

- Psychoeducation and peer-support groups can address this heteronormativity through providing appropriate support to LGBTQ+ youth to understand it, cope with it, and ultimately reject it.

(2) Meso inner ring 2

- This ring highlights the various steps mental health services should take to ensure effective early intervention in mental health care.

- It highlights the importance of recognising the plurality and fluidity of gender and sexuality to foster a positive identity within the individual.

- Similarly, it is essential to realise that there is no fixed pathway or destination to sexual and gender identity – there is always a sense of becoming.

- Also, services should foster positive relationships for LGBTQ+ youth by ensuring trustful and supportive interactions.

- Further, individuals should feel a sense of belonging and safety in the support service.

- Lastly, there is a need for intelligibility, whereby practitioners can comprehend and understand individuals’ unique identities and experiences.

(3) Micro ring 3

- This section discusses the importance of how the individual is treated in mental health services.

- It is important that LGBTQ+ youth are given agency and autonomy to make decisions about their care.

- Furthermore, services must recognise the strengths and resilience of the person.

(4) Centre ring 4

- The core of the framework discusses how mental health is conceptualised.

- It is essential to get a well-rounded view of an individual by considering emotions, distress, and subjectivity. Therefore, turning away from rigid diagnostic categories.

Clinicians can adopt a curious stance and ask a young person whether there are any parts of their identity that they would like them to keep in mind.

Conclusions

The developed framework highlights how LGBTQ+ youth mental health support can be improved at different levels.

The key starting points are:

- Recognising the impact of living in heteronormative environments

- The importance of facilitating young persons’ autonomy and encouraging agency

- Understanding that a mental health diagnosis is not necessary, nor should it impede access to support.

The present theoretical framework can likely guide the development of effective mental health strategies and interventions for LGBTQ+ youth.

The framework avoids pathologising emotional distress and advocates for youth-centred LGBT+ support that attends to complex factors influencing mental health.

Strengths and limitations

The present review has produced the first theoretical framework for enhancing LGBTQ+ youth mental health. This is crucial considering the worse mental health outcomes in this community compared to heterosexual peers (Amos et al., 2020). Another positive of this review is the inclusion of studies written in various languages, including English, Spanish and French. Many other reviews only include studies written in English; therefore, this review likely provides a more comprehensive understanding of the literature. However, it would have been even better if researchers were able to include studies written in non-European languages, to enhance the generalisability of the findings further.

There are a few more limitations present. Firstly, the PICO strategy, commonly used in systematic reviews for identifying studies, may not have been entirely in line with the nature of the present meta-narrative review. As meta-narrative reviews are iterative and interpretive, the use of methods designed for more linear processes is rather challenging. A possible explanation is that meta-narrative reviews use several paradigms as units of analysis and include studies across different study designs. Therefore, the criteria applied to assess the studies should reflect the standards of each paradigm and research design included. Lastly, although the authors mentioned evaluating the quality of the individuals’ studies, there was no report of the quality of the studies in the actual paper. Therefore, it is not possible for us as readers to be confident about the quality of the studies included in this review.

Research can help us understand how to best support LGBTQ+ youth mental health, considering literature from a wide range of cultures.

Implications for practice

Clinicians should aim to better understand intersectionality and recognise an individual’s multiple identities that may overlap. The latter can lead to the provision of more tailored support. For instance, although all LGBTQ+ youth grow up and live in a heteronormative world, the benefits of treatment are also influenced by an individual’s race, ethnicity, social class, etc. When in doubt, clinicians can adopt a curious stance and ask a young person whether there are any parts of their identity that they would like them to keep in mind.

Health professionals should have in mind that they are working with young people; however, this should not stop them from supporting young people to take ownership of their care. Adopting a collaborative stance, making decisions jointly, and appreciating youth knowledge can empower them. Psychoeducation can be key to promoting self-esteem, understanding, and coping strategies.

Clinicians are also encouraged to provide treatment support irrespective of whether a young LGBTQ+ person has a mental health diagnosis or not. In fact, a young person’s subjective assessment of mental health should be adequate to access support. The latter can increase the uptake of mental health support among young LGBTQ+ people. Subsequently, moving away from pathologising emotional distress can minimise the stigma and facilitate access to support early in young LGBTQ+ persons’ difficulties.

This review guides clinicians to promote agency and autonomy in young LGBTQ+ youth, acknowledge intersectionality and move away from medicalising emotional distress.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

McDermott, E., Eastham, R., Hughes, E., Pattinson, E., Johnson, K., Davis, S., … & Jenzen, O. (2021). Explaining effective mental health support for LGBTQ+ youth: a meta-narrative review. SSM-mental health, 1, 100004.

Other references

Amos, R., Manalastas, E. J., White, R., Bos, H., & Patalay, P. (2020). Mental health, social adversity, and health-related outcomes in sexual minority adolescents: a contemporary national cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 36-45.

Gough, D. (2007). Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research papers in education, 22(2), 213-228.

Jagosh, J., Pluye, P., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Henderson, J., Sirett, E., … & Green, L. W. (2011). Assessing the outcomes of participatory research: protocol for identifying, selecting, appraising and synthesizing the literature for realist review. Implementation science, 6(1), 1-8.

Semlyen, J., King, M., Varney, J., & Hagger-Johnson, G. (2016). Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low wellbeing: combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC psychiatry, 16(1), 1-9.

McDermott, E. (2015). Asking for help online: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans youth, self-harm and articulating the ‘failed’self. Health:, 19(6), 561-577.

McDermott, E., Hughes, E., & Rawlings, V. (2018). Norms and normalisation: understanding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer youth, suicidality and help-seeking. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 20(2), 156-172.

Wilson, C., & Cariola, L. A. (2020). LGBTQI+ youth and mental health: a systematic review of qualitative research. Adolescent Research Review, 5(2), 187-211.

Photo credits

- Photo by Shingi Rice on Unsplash

- Photo by Helena Hertz on Unsplash