Novel psychoactive substances (NPS; also known as new psychoactive substances or popularly, although erroneously, as ‘legal highs’) is the name given to drugs that are newly synthesised or newly available, and which do not fall under the control of United Nations Drug Conventions. These drugs exist as a result of advances in academic, industrial, and psychonautic chemistry and are used for many of the same reasons given for traditional illegal drugs such as cannabis, ecstasy, and heroin. However, many NPS are not detected by routine forensic screens, and so are relatively popular in secure settings such as prisons, or in professions that are subject to random drug screening programmes.

Novel Psychoactive Substances may also be controlled under national drugs legislation, and so in the UK, drugs such as mephedrone or the synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRA, ‘Spice’) are often called NPS despite being controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (the ‘ABC’ classification system). Furthermore, the introduction of the UK Psychoactive Substances Act in May 2016 has meant that unless specifically exempted (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, approved foodstuffs), the manufacture, distribution and retail of all psychoactive substances are now controlled in law. This legislation does not include a personal possession offence, which means that NPS are treated differently from traditional drugs, although the government can move an NPS into the Misuse of Drugs Act if it is concerned about the societal harms that it produces, or has the potential to produce. A useful example of the unintended consequences of such legislation is revealed in a recent snapshot survey of drug use, where some people reported self-medicating with heroin to recover from the effects of spice, whereas in other locations people are using spice to cut down on heroin consumption.

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) network of Early Warning Systems has detected over 560 NPS since the mid-2000s. These comprise a variety of chemical classes, and acknowledging exceptions, can be broadly classed as stimulant-, cannabinoid-, hallucinogen-, dissociative-, opioid-, and benzodiazepine-like drugs. The diversity and complexity of NPS pharmacology, and the potential array of psychopharmacological and toxicological effects they produce means that it is too simplistic to consider these as one class of drug, although they are often popularly discussed as such. For example, nitrous oxide (‘laughing gas’) and the benzodiazepine-like etizolam are both classed as NPS, but the former is relatively harmless compared to the latter which has been associated with a high number of deaths in a short space of time.

Many novel psychoactive substances have become popular in prison settings and some professional groups because they are not detected by routine forensic screens.

Novel Psychoactive Substances: prevalence

Despite great public, media, and political attention, prevalence of use of NPS in the general population of adults and young people is considered to be low. Most of the NPS detected by the EMCDDA fail to diffuse to recreational markets, and the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) estimated that in 2015/16 fewer than 1 in 100 (0.7%) adults aged 16-59 reported use in the last year. Prevalence is slightly higher in 16-24 year olds (2.6%) and school children aged 11-15 (2.5%).

Although government surveys no longer collect data on use of individual compounds, based on the findings of earlier surveys, it is likely that most experiences with NPS are through use of nitrous oxide. As with traditional illegal drugs, research suggests that prevalence of use is much higher, or is associated with a greater likelihood of harm in some sub-populations. NPS users are diverse and shouldn’t be considered an homogenous group, but clustering together individuals with shared characteristics and use behaviours is useful in understanding likely clinical need and response.

Despite what the media tries to tell us, prevalence of use of Novel Psychoactive Substances in the general population is considered to be low.

High risk groups

Relevant groups of Novel Psychoactive Substances users include clubbers and festival attendees, men who have sex with men, young people (who are considered vulnerable because of their stage of development), problematic drug users (in particular people who inject drugs (PWID)) and those who require support with mental health. Particular concern has been raised over use of SCRA (generically known as ‘Spice’) and its associations with violence and adverse mental health outcomes in prisoners (see Ralphs et al, 2017) and those who are homeless or vulnerably housed, including in Scotland.

These higher-risk groups often have multiple and complex needs and use NPS in harm-promoting environments, meaning that identifying and delivering treatment and intervention responses is particularly difficult, and needs to encompass wider actions than simply focusing on drug use and drug user disorders.

Useful resources

Partly as a result of the novelty and diversity of Novel Psychoactive Substances, a lack of evidence on potential harms from use, and the emergence of new user behaviours, drug workers and health care professionals report low confidence in responding to use by the clients and patients they encounter.

Two recent articles published in the British Medical Journal (Tracy et al, 2017a; Tracy et al, 2017b) aim to support non-specialist clinicians to respond to individuals who present in relation to suspected use of NPS. These pieces sit alongside other resources such as the NEPTUNE clinical guidance, the EMCDDA’s recommendations (PDF) for health and drug related interventions for higher-risk NPS using populations, and the UK Home Office NPS resource pack for informal educators and practitioners. A common feature of all these tools is that they build upon the skills and competencies that workers are already likely to, or should be expected to, possess.

Novel Psychoactive Substances: categories

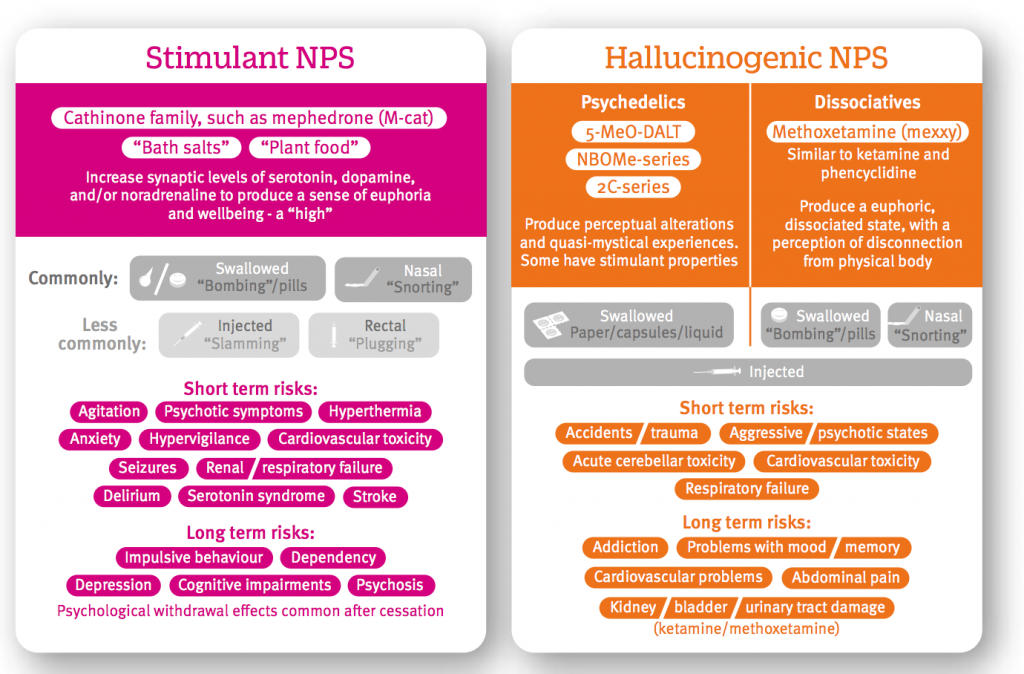

Tracy and colleagues provide a concise overview of the pharmacology and toxicology of four major Novel Psychoactive Substances categories:

- Stimulants (e.g. mephedrone)

- Cannabinoid NPS (SCRA or ‘Spice’)

- Hallucinogens (e.g. methoxetamine, the NBOMe series)

- Depressants (e.g. benzodiazepine and opioid like NPS such as flubromazepam and AH-7291).

This categorisation is useful for acute presentations, as although emerging bodies of research suggests some differences, clinical presentations, where they have been characterised, are broadly similar to those traditional drugs classes more familiar to the clinician. Indeed, across both papers, much of the advice and information is based on approaches adopted from responses to drugs such as heroin, cannabis, and cocaine. This is partly due to the importance of building upon clinical existing skills, but also practical considerations; without toxicological screening neither the clinician nor the patient is unlikely to know precisely what drug may be associated with the presentation, as self-report of NPS is not particularly reliable due to the illegal market, the rapidly changing nature of products in the NPS market, and the use of local slang terms.

The same but different

Unsurprisingly, some important differences between Novel Psychoactive Substances and their traditional counterpart substances have been noted. Methoxetamine, which was originally marketed as an alternative to the dissociative agent ketamine, shares many of its acute harms including renal and bladder toxicity. However, it produces greater hypertension, and produces some unique stimulant effects not shared with ketamine, such as tachycardia (faster heart rate) and ataxia (unsteadiness). Inclusion of specific NPS in guidance such as these is sometimes problematic though. Whilst methoxetamine was briefly popular earlier in this decade, after legal control (it is now a Class B drug under the 1971 MDA) it all but disappeared from retailers, and was soon replaced with other dissociative arylcyclohexylamine drugs, of which less is known.

The cannabinoid group of NPS, widely known as SCRAs, are the most widely available. Although there are important discussions of evidence around the potential mental health harms of cannabis, it produces few of the acute harms associated with SCRA (often incorrectly and unhelpfully described as ‘synthetic cannabis’). In addition to being associated with deaths (8 were registered in 2015) reviews of hospital presentations show profiles that range from more frequently encountered agitation and nausea (usually resolved through reassurance and symptomatic care), to rarer, but more serious complications requiring in-patient stays including cardiovascular events (including myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke), hyperemesis (severe nausea and vomiting), and psychiatric complications (including first episode psychosis, paranoia, self-harm/suicide ideation, hallucinations, self-injury, panic, anxiety, Capgras delusion, catatonia).

There is currently no evidence to suggest that users of NPS are at greater risk of experiencing mental ill health, but an analysis of discharge letters of patients leaving general psychiatric wards in one large Scottish hospital suggested that NPS use was identified in 22.2% of admissions over a 6 month period (n=483), and judged to contribute to psychiatric symptoms in 59.3% of cases.

Case series studies suggest that SCRAs can produce physical withdrawal symptoms (in addition to psychological withdrawal mentioned by Tracy and colleagues) that are more pronounced than for cannabis, but people can present to drug treatment services for many different reasons other than just ‘dependence’ (e.g. impact of substance use on relationships, employment, education and criminality). Data from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) showed that in 2015/16, there were 2,042 new presentations to drug treatment services in England, predominately relating to problems associated with SCRA use. This had risen from 320 in 2013/14 partly as a result of better data collection, but also due to opening of new services specifically for NPS users, and the emergence of NPS related harms after prolonged use in some users. This compared with 1,318 ecstasy related presentation, 1,647 mephedrone presentations, and 7,095 for cannabis.

Case series studies suggest that synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists can produce physical withdrawal symptoms.

Intervene or refer?

Tracy and colleagues recommend referral to drug treatment services where appropriate, but it is uncertain whether drug treatment services are optimally orientated to support those presenting with NRS-related needs. Where a patient discloses use of NPS the authors suggest the use of motivational interviewing (MI) approaches to encourage them to reflect on their use behaviours with a view to making changes. Of what limited evidence there is, it is suggested that MI works most effectively when used alongside CBT. Systematic reviews and meta analyses of screening and brief intervention approaches (including MI) delivered in primary care/hospital settings provide some evidence that these can be effective in changing alcohol consumption although questions have been raised over the clinical relevance of effects observed in trials of brief interventions. In contrast, the effectiveness of MI on use of illicit substances (and by extension NPS) is understudied in these settings.

Are drug treatment services ready and waiting for NPS referrals from health services?

Injecting Novel Psychoactive Substances

Novel Psychoactive Substances pose additional behavioural risks. Some stimulant NPS (e.g. ethylphenidate) have been reported to be injected several times a day in extended use episodes. In evidence submitted to the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, police in Scotland reported observations in such sessions of injection in unsanitary condition, communal injecting and injecting equipment sharing, high risk injecting practices (e.g. injecting in the groin), inappropriate preparation of drugs (e.g. use of corrosive citric acid to dissolve drugs, where none was needed), and injection site damage due to a loss of motor control as a result of intoxication. Such risk factors may underlie the association between injection of the NPS alpha-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (α-PVP) and HIV infections among homeless PWID in Dublin, and Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes infections in people who injected ethylphenidate in Edinburgh.

Conclusion

The BMJ articles are timely as many workers lack confidence when working with people who use NPS, in part because they lack knowledge about what these substances are and the impact they have on health.

Hopefully this blog reassures you that while there are some useful resources you can draw on, there is much more we need to explore and understand about the risks of using NPS.

Health workers need to improve their NPS knowledge so they can work more confidently with this growing group of service users.

Links

Primary papers

Tracy DK, Wood DM, Baumeister D. (2017a) Novel psychoactive substances: types, mechanisms of action, and effects. BMJ 2017; 356 :i6848

Tracy DK, Wood DM, Baumeister D. (2017b) Novel psychoactive substances: identifying and managing acute and chronic harmful use. BMJ 2017; 356 :i6814

Photo credits

- Patrick Denker CC BY 2.0

- Dragan CC BY 2.0

- Ninian Reid CC BY 2.0

- ☻☺CC BY 2.0

- By Lance Cpl. Damany S. Coleman, US Marine Corps 100201-M-3762C-001

[…] Novel Psychoactive Substances: important information for health professionals […]