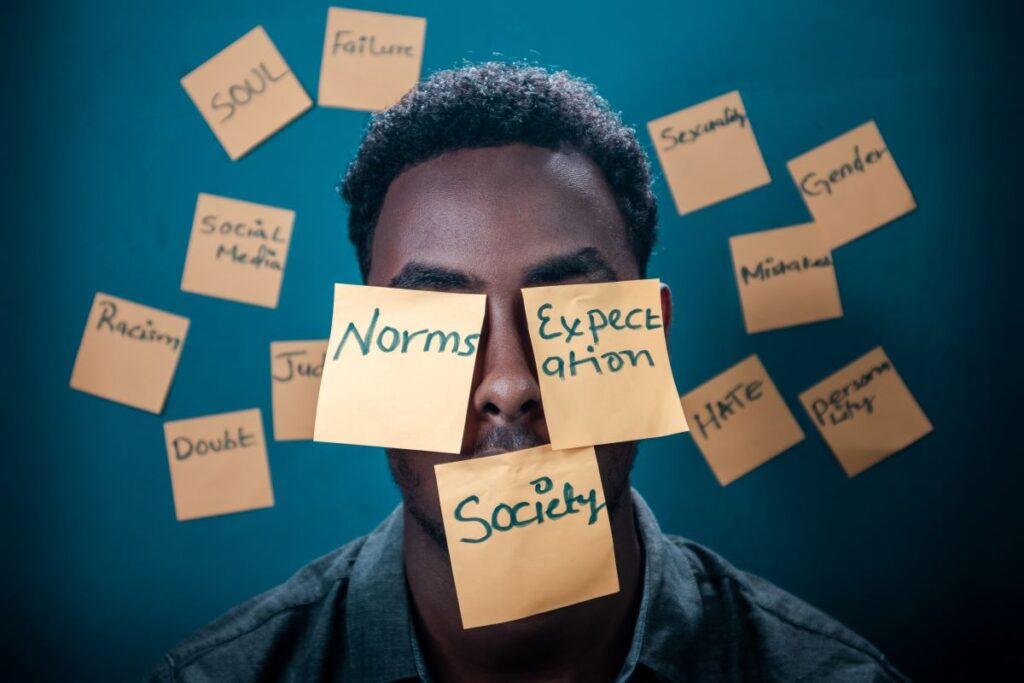

Stigma against people with mental illness is bad. Not bad as in offensive. Nobody complaining about stigma is complaining about being offended. They’re also definitely not complaining about names causing hurt feelings. You arsehole. Stigma against people with mental illness is bad because it worsens symptoms, leads to worse outcomes and prevents people from seeking help in the first place (Oexle N, et al. 2015).

As if stigma, negative beliefs about a person or group based on perceived stereotyped characteristics, from everyone else isn’t bad enough, exposure to this discrimination can become internalised so that the person experiencing it comes to believe the negative stereotypes about themselves (Bradstreet S, et al 2018). Sorry about earlier. You’re not an arsehole. Just as with external stigma, internalised stigma worsens symptoms, outcomes and reduces help-seeking behaviour in individuals with mental illness. (Drapalski A, et al. 2013)

As a result of internalised stigma being a bad thing that should be stopped, there are several interventions that attempt to stop it. Like most interventions, it’s probably worth checking if they actually “intervene”. One such check examined the efficacy of Ending Self-Stigma, a nine-session group intervention designed to teach individuals experiencing mental illness a set of tools and strategies to effectively deal with self-stigma and its effects.

Internalised stigma worsens symptoms, outcomes and reduces help-seeking behaviour in individuals with mental illness

Methods

Participants (n = 248) were recruited from outpatient mental health clinics for veterans and randomly assigned to attend either the Ending Self-Stigma course or a nine session Health and Wellness intervention, with a focus on providing education and support regarding general physical wellbeing. The Ending Self-Stigma course comprises education in psychological techniques and aspects of cognitive behavioural therapy to allow participants to build a more positive view of themselves. This can include lectures, sharing of personal experiences and problem solving. It seems a shame people can’t get this to stop stigmatising! Participants were predominantly male (87%) and had diagnoses of schizophrenia disorder (25%), schizoaffective disorder (26%), or bipolar disorder (42%). The mean age of participants was 53.4 years.

Prior to and following each intervention (with an additional 6-month follow up), participants completed the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale of the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (SSMIS). Other recovery-related measures were used, including but not limited to the Maryland Assessment of Recovery in Serious Mental Illness scale and the Brief Symptom Inventory. Analyses were performed with the intention to treat sample.

Results

Participants randomly assigned to the Ending Self-Stigma group attended an average of 4 group sessions out of nine and participants assigned to the Health and Wellness group attended an average of 3 group sessions out of nine each. Perhaps the biscuits were sub-par.

Both groups achieved reduced scores for internalised stigma and increased scores for measures of wellbeing. These improvements were found to be maintained at the 6-month follow-up. There were no significant differences between the two groups either for post-treatment internalised stigma score nor for measures of wellbeing.

A high level of psychotic symptoms seemed to impact the treatment effect, with those individuals in the Ending Self-Stigma group who rated highly for psychosis experiencing a greater reduction in internalised stigma than those in the Health and Wellness group with similarly high psychosis symptom reporting. Still no mention of the biscuits.

There were no significant differences between the two groups either for post-treatment internalised stigma score nor for measures of wellbeing.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that while numerous interventions may help in reducing internalised self-stigma in veterans with severe mental illness, those with high levels of psychosis-related problems may benefit from an intervention specifically aiming to reduce internalised stigma, such as the Ending Self-Stigma intervention.

Those with high levels of psychosis-related problems may benefit from an intervention specifically aiming to reduce self-stigma, such as the Ending Self-Stigma intervention.

Strengths and limitations

It is positive that this is a randomised controlled trial, allowing some inferences to be made regarding the cause of improvements, if improvements were to be observed. Unfortunately, there were no real differences between the two groups, although perhaps this too can be seen in a positive light. It could be argued that it is a good thing that a specific intervention regarding reducing self-stigma is not needed and that a general intervention focussing on wellbeing, with other attendant benefits for physical and mental health, will do just as well.

The population sampled was relatively specific, comprising veterans with schizophrenia, schizoaffective or bipolar disorder. As such, the findings here may not be applicable to other groups. For example, it would be useful to know if internalised self-stigma could be reduced in the general population with mixed anxiety and depression, the most common mental illness in the UK (NICE, 2011). However, veterans are most definitely an underserved population, as are those with the diagnoses present in the population sampled, and it is certainly useful to determine if a relatively simple intervention can improve wellbeing in both groups (Atkins D, et al. 2014; Larkin M, et al. 2017).

It is noticeable from the results that neither intervention had great attendance. As such, it could be argued that any improvement might just be due to time elapsed rather than anything purposeful that was done in the limited time spent within the groups. If we’re being generous, we could simultaneously argue that the interventions are so effective that you only need to attend half of them. Wouldn’t it be nice if you could ultimately help twice as many people? If they showed up.

The authors argued that those with more psychotic symptoms may have seen greater benefit from the Ending Self-Stigma intervention than those with fewer psychotic symptoms because these experiences and behaviours are closer to the negative stereotypes held about mental illness. This could mean the impact of self-internalised stigma is greater and a more specific intervention is needed for people with more severe psychotic symptoms. However, this conclusion was based on an exploratory analysis only and should therefore be interpreted with caution. It would be useful to see if symptoms of psychosis modulated the initial levels of internalised stigma to support this claim.

The population sampled was relatively specific, comprising veterans with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder – therefore these findings may not be generalisable to other populations.

Implications for practice

The implications of this research are reasonably straightforward, in that it would clearly be of benefit to provide some sort of wellbeing intervention for those with severe mental illness. In addition, a more specific focus on self-stigma reduction may be required for those with high levels of psychosis.

It seems a shame that a group-specific intervention is needed for what is essentially a societal problem. Self-stigma exists because stigma exists and if the wider public were more informed about why their negative stereotypes were not correct, then the problems of internalised stigma would at least be reduced. Apparently, we are in a situation where it is easier to treat the minority for a problem that is caused by the majority. It would clearly be better if there could be a focus on improving the wellbeing and symptoms of those with severe mental illness, where such help is even available, rather than also having to think about additional damage caused by the overall population. The arseholes.

Should we be targeting the minority who experience self-stigma or the majority of society whose misinformed negative stereotypes cause and perpetuate self-stigma?

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Brown CH. et al (2021) Outcomes of Ending Self-Stigma, a Group Intervention to Reduce Internalized Stigma, Among Individuals With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv 72(2):136-142.

Other references

Atkins D, Kilbourne A, & Lipson L (2014) Health Equity Research in the Veterans Health Administration: We’ve Come Far but Aren’t There Yet. Am J Public Health 104(Suppl 4): S525–S526.

Bradstreet S, Dodd A, & Jones S (2018) Internalised stigma in mental health: An investigation of the role of attachment style. Psychiatry Research 270: 1001-1009.

Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Perrin PB. Et al (2013) A Model of Internalized Stigma and Its Effects on People With Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv 64(3):264-269.

Larkin M, Boden Z, & Newton E (2017) If psychosis were cancer: a speculative comparison. Medical Humanities 43:118-123.

NICE (2011). Common mental health disorders | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. [online – Accessed 28 Feb 2021].

Oexle N, et al. (2015) Mental illness stigma, secrecy and suicidal ideation. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 26:1–8.

Photo credits

- Photo by Vince Fleming on Unsplash

- Photo by Barefoot Communications on Unsplash

- Photo by Ben Weber on Unsplash

- Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

- Photo by Daniel Ioanu on Unsplash

- Photo by Yasin Yusuf on Unsplash