Many research studies and articles in the media often use the terms ‘mental illness’ and ‘emotional wellbeing’ interchangeably.

Some studies aiming to investigate wellbeing end up measuring mental illness outcomes (e.g. Maynard et al., 2010). So, what’s the difference?

- Mental illness is typically characterised as disordered thinking, emotions and behaviour.

- Emotional wellbeing can be viewed as representing the positive aspects of mental health, such as the feeling of functioning in each of the aspects of one’s life.

There is extensive debate around whether these two definitions are part of the same continuum or two separate domains entirely (e.g. Huppert et al., 2014).

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry aimed to address this question by exploring the predictors of mental illness and wellbeing using a large epidemiological sample (Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2016).

‘Mental illness’ and ‘emotional wellbeing’ are often used interchangeably, but are they even part of the same domain?

Methods

12,347 children aged 11 were surveyed from the UK.

This was part of data collected for the Millennium Cohort Study: a mixture of measures given to individuals born between 2000-2002. This was Wave 5 of the study, recorded when the participants were aged 11.

Study participants were a good representation of the UK demographics, including sex, ethnicity and socio-economic background.

Measures

Mental illness: Parents used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to rate their child’s mental ill health. The scores generated from this were totalled to make a ‘mental ill-health score’.

Emotional wellbeing: Mental wellbeing was self-rated by the 11 year olds participants. This was a measure previously used in the British Household Panel Study of happiness in six different areas of their life (school, family, friends, school work, appearance and life as a whole). The scores from this questionnaire were aggregated to form a wellbeing score.

Other measures

Also included in the the Millennium Cohort Study were measures of ethnicity, socio-demographic status, cognitive and health factors, family structure, home environment, parent health, social relationships and wider environment (e.g. child perspectives of school connectedness).

Analysis

The correlation between each of the variable outcomes was calculated. Stepwise regression analyses were conducted to see what factors best predicted mental illness and wellbeing.

Results

There was a low correlation (r = .2) between mental illness and wellbeing measure outcomes.

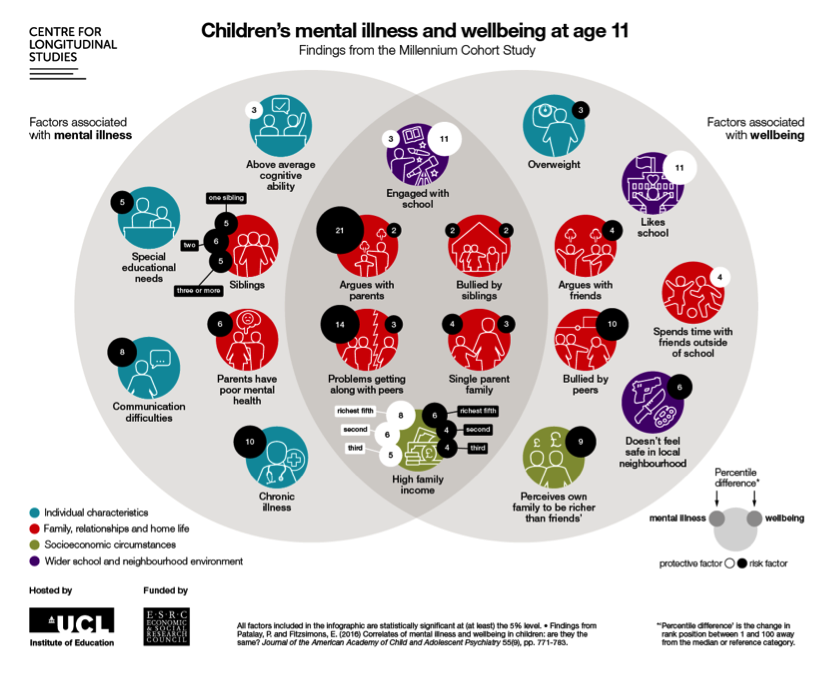

Interestingly, the significant predictors of mental illness scores were different to those that significantly predicted wellbeing outcomes.

Mental illness

- 47% of the variance of mental illness outcome scores was explained by the predictor variables

- The main predictors of outcome were:

- Cognitive factors

- Home environment factors

- Parent health

- Social relationships

- Mental illness scores were significantly higher for children with:

- Communication difficulties

- Chronic illnesses

- Peer relation problems

- Frequent arguments with a parent

- Mental illness scores were significantly lower for children with:

- High family income

Emotional wellbeing

- 26% of the variance of wellbeing scores was explained by the predictor variables

- The main predictors of outcome were:

- Social relationships

- The wider environment

- The highest individual predictors of wellbeing were:

- Perceived school connectedness

- Liking school

- Peer bullying

Ethnicity was a significant predictor for mental illness but not emotional wellbeing. Black, Asian or ethnic groups other than White predicted lower mental illness scores.

Strengths and limitations

- This epidemiological study has a large sample size and uses very representative demographics, meaning that the results are more generalisable to the UK population.

- One major limitation of comparing the mental illness and wellbeing measures is that they have different reporters. The mental illness measure is parent-reported, whilst the wellbeing measure is self-reported by the young people themselves. The understanding of somebody’s mental experiences will differ between parents and the young people themselves, and it may be that the low correlation between measures can be explained mainly due to reporter differences. However, in a similar study correlating self-reporting mental ill health and perceived quality of life in 13 year olds, correlation scores remained low at r = .22 (Sharpe et al., 2016).

- To better investigate this problem, the next Wave of the Millennium Cohort Study conducted later this year will contain self-rated measures of mental illness and depression.

- SDQ scores were used to give a measure of ‘mental illness’. However, this measure compiles both externalising disorders (e.g. conduct disorder) with internalising disorders (e.g. depression). It may be the case that whilst externalising disorders do not correlate highly with wellbeing, internalising disorders do correlate more highly. It would be interesting to see analyses measuring the correlation of the internalising disorders score alone with the other predictor measures.

- The validity of the measure of wellbeing should be questioned. The original measure asked participants to rate their happiness in six different domains. The definition of wellbeing is not concrete and different questionnaires of wellbeing may not be measuring the same concepts.

- The factors that predicted wellbeing in this study are mainly associated with school. The used measure of wellbeing has six questions. Two of these questions are about school, making up a large proportion of the total score. This ‘school-weighted’ measure may be a reason why school factors are more significant predictors for this measure of wellbeing.

One major limitation of this research was that mental illness was measured by asking parents and emotional wellbeing was measured by asking young people.

Summary and conclusions

This excellent study is a broad and in-depth exploration of the predictive factors of mental illness and wellbeing in 11 year olds.

- Wellbeing is better predicted by aspects of a child’s social and relationship life, such as peer bullying and perception of school connectedness.

- However, mental illness is better predicted by chronic and health conditions, as well as ethnicity.

The low correlation between mental illness and wellbeing outcomes suggests that these are largely distinct but overlapping domains.

The authors write:

Correlates of children’s mental illness and wellbeing are largely distinct, stressing the importance of considering these concepts separately and avoiding their conflation.

Future studies should investigate whether parent-rated measures of mental illness are as accurate as child-rated measures. It would also be interesting to see whether these differences are maintained in further adolescent and adult development.

This finding may explain why there is limited evidence supporting emotional wellbeing interventions improving mental ill health outcomes.

Mental illness and emotional wellbeing may overlap less than we’d previously thought.

Links

Primary paper

Patalay P, Fitzsimons E. (2016) Correlates of Mental Illness and Wellbeing in Children: Are They the Same? Results From the UK Millennium Cohort Study (PDF). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(9), 771–783.

Other references

Huppert FA. (2014) The state of wellbeing science: concepts, measures, interventions, and policies. In: Huppert FA, Cooper CL. eds. Interventions and Policies to Enhance Wellbeing. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 1-50.

Maynard M, Harding S. (2010) Ethnic differences in psychological well-being in adolescence in the context of time spent in family activities. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 115-123.

Sharpe H, Patalay P, Fink E, Vostanis P, Deighton J, Wolpert M. (2016) Exploring the relationship between quality of life and mental health problems in children: implications for measurement and practice. European Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 659-667. [PubMed abstract]

Photo credits

- Paul Brou CC BY 2.0

- By MichaelMaggs (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

I’m a little confused. Surely ethnicity, chronic health can very massively impact connectedness and relationships. Perhaps our interventions are simply not providing enough to help those who society struggles to connect with?

Also confused at why distinct but overlapping isn’t a continuum? You would expect bigger differences between either end?

Maybe am not awake yet!

Thanks

This is a nice post. It could be used as the starting point of lots of discussions. Here’s one: Does the research method itself (using internal measure of wellbeing and external measure of illness) immediately clarify the difference between the two, and why they are not a continuum? We define mental illness from the outside, yet what people are struggling with is their subjective experience. Your post defines the study as the subject, which wraps the whole thing up! I suspect that in this respect the post may be more excellent than the paper, but I haven’t read the paper yet, so I should do that now.

not sure SDQ = mental illness (depression, anxiety, psychosis, bipolar etc.)