Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate among all psychiatric disorders (Yao et al., 2019) and remains difficult to treat.

Recent research has shed light on the link between anorexia nervosa and autism, and it’s estimated that 20-30% of individuals with anorexia nervosa will also meet the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder (Westwood & Tchanturia, 2017). Elevated levels of autistic traits in anorexia nervosa populations are commonly observed, showing similar rigid thinking patterns, cognitive, social and behavioural difficulties in both groups.

While these behaviours can be induced by starvation and were found to resolve with weight restoration in anorexic individuals (Treasure, 2013), autistic women may continue to show these patterns. Furthermore, autistic women may show autism-specific factors that underpin their anorexia nervosa, which was qualitatively explored (Brede et al., 2020), indicating that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-ED) for anorexia nervosa may not be beneficial for autistic individuals. Factors associated with maintenance of anorexia nervosa behaviours, such as focus on weight and food, are less of a concern in autistic individuals.

In addition, clinicians have been found to lack experience and confidence in treating individuals with anorexia nervosa and autism (Kinnaird, Norton & Tchanturia, 2017), which demonstrates the need for greater awareness of this issue among services and clinicians, to facilitate better treatment outcomes for individuals with anorexia nervosa and autism.

Therefore, Babb et al. (2021) qualitatively explored the eating disorder (ED) service experiences of autistic women with anorexia nervosa, their parents, and healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Around 20-30% of individuals with anorexia nervosa will meet diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder.

Methods

Across the UK, 15 autistic women with an official autism diagnosis and (past or current) experience of anorexia nervosa, 13 parents of autistic women with experience of anorexia nervosa and 11 healthcare professionals (HCPs) were recruited. HCPs had experience of working in eating disorder (ED) services and working with autistic individuals.

Participation involved completion of AQ-10 to measure autistic traits and Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire short form (EDE-QS) to measure current ED symptomatology in autistic women. Interview schedules were developed with the help of two autistic advisors with lived experience of anorexia nervosa, to cover the experience and diagnosis of autism and anorexia nervosa, which were adapted for parents. Interviews with HCPs focused on experience and awareness of autistic women in ED services. Interviews took place either face-to-face, over phone or via Skype.

The interviews were then transcribed verbatim and entered into NVivo 12 for qualitative data analysis, using an inductive, essentialist approach of thematic analysis to identify themes and patterns in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Additionally, autistic advisors provided feedback on the accuracy of themes, to ensure representativeness of the autistic voice.

Results

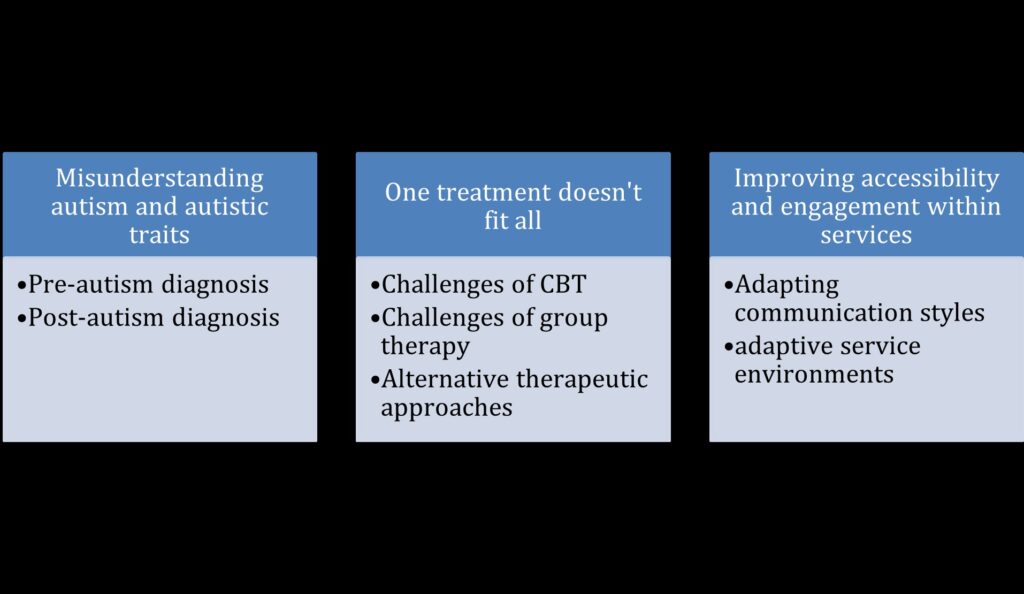

Analysing datasets of the three stakeholder groups, the following three themes and sub-themes unfolded:

Misunderstanding autism and autistic traits

The first theme discusses the difficulty of understanding autism in the anorexia nervosa population. The sub-themes of pre- and post-autism diagnosis recognises the difficulties of overlapping symptoms, such as rigidity in thinking patterns. Communication difficulties in autistic women were often interpreted as lack of engagement across HCPs, which left autistic women being labelled as ‘treatment resistant’ or ‘too complex’ to be treated. Additionally, even after having received an autism diagnosis, autistic women reported lack of appropriate support and consideration by services. HCPs reported lack of resources, as well as insufficient training to support autistic women with anorexia nervosa appropriately, making it increasingly difficult to meet autistic women’s needs in ED services.

One treatment does not fit all

Most women reported negative experiences of CBT and described difficulties with engaging in therapy, and application of skills learned. Although some women reported benefits, the majority of autistic women and parents had a negative view.

Managing social demands of group therapy was reported to be challenging for autistic individuals, which negatively impacted their ability to engage. Consequently, HCPs attributed lack of engagement to rudeness or lack of motivation, which misconstrues individuals’ social difficulties experienced.

In comparison, highly structured group therapy, such as DBT (dialectical behaviour therapy), was found to be more helpful due to its structure and focus on emotion regulation by participants. Occupational therapy was also reported to be helpful, since it employs a more practical approach. Other adjustments to therapy (e.g., handouts) enabled individuals to feel more prepared and reduce anxiety to uncertainty. Overall, focus on emotion regulation and practical skills were experienced as more useful by autistic women, as it took away the focus from food, weight and body image, which plays less of a role in autistic women with anorexia nervosa (Brede et al., 2020).

Improving accessibility and engagement within services

The key to engagement with services was shaped by effectiveness of communication with HCPs. Autistic women also described that experience of effectiveness was not consistent across the team, which emphasises the need for awareness and training across services. Autistic women often expressed the wish for a clear structure and timetable, to support their experience in a new environment. Accommodating sensory sensitivities and increasing predictability of routine should be implemented at service level, to aid women’s ability to engage.

Standard anorexia nervosa treatment does not meet autistic women’s needs, making it difficult for individuals to engage and benefit from treatment.

Conclusions

The findings underline a lack of appropriate treatment support for individuals with autism and anorexia nervosa. Misinterpretation of overlapping symptoms among HCPs demonstrates the need for an improved understanding of autism and anorexia nervosa when they co-occur. Interestingly, all women received an autism diagnosis after having seen ED services, which can be attributed to symptoms of autism being overshadowed by mental health difficulties (Leedham et al., 2020). Thus, increasing awareness, promoting training for HCPs and implementing treatment adaptations may benefit autistic individuals in ED services to receive more valuable, individualised care (Tchanturia et al., 2020).

Increasing awareness and training among healthcare professionals is needed to prevent symptoms of autism being overshadowed by mental health difficulties.

Strengths and limitations

The study used in-depth interviews to gather experiences of eating disorder (ED) services from three different stakeholder perspectives. This allowed a more comprehensive overview of the challenges faced by individuals with autism and anorexia nervosa, as well as parents and health care professionals (HCPs). Consequently, results will hopefully inform commissioners on more relevant treatment guidelines for autistic individuals with anorexia nervosa. Additionally, a participatory approach ensures validity of themes to account for accurate interpretation of qualitative findings. Although it needs to be considered that two autistic individuals will not represent every autistic individual’s view.

Furthermore, the study only included autistic women with anorexia nervosa. Despite the fact that anorexia nervosa is more commonly observed in women (Yao et al., 2019), it would be interesting to explore the experience of autistic men, non-binary and transgender individuals with anorexia nervosa in ED services. Since men have previously reported negative experiences of ED services (Richardson & Paslakis, 2021), inclusion of other groups is needed to make treatment for individuals with autism beneficial for everyone. Lastly, including a comparison group of individuals with anorexia nervosa may be helpful to further detangle autism specific difficulties.

Findings may not be generalisable for all individuals with autism and anorexia nervosa, since men (and other gender diverse people) were not included in the sample.

Implications for practice

- The current study indicates that NICE treatment (NICE, 2017) for anorexia nervosa does not meet autistic needs and is unlikely to be successful.

- To improve treatment outcomes for individuals with autism and anorexia nervosa, greater awareness and recognition of autism is needed across health care professionals (HCPs).

- Furthermore, adaptations may help individuals to engage and facilitate recovery. Since CBT is successfully adapted for autistic individuals for other psychiatric disorders (Lang et al., 2010), adapting CBT for anorexia nervosa may also be successful.

- Considering the fact that autistic traits are common in people with anorexia nervosa, they should be taken into consideration when offering treatment (Westwood et al., 2016).

- Thus, future research is needed to tailor interventions to individuals with autism and anorexia nervosa.

Future research should focus on implementation of treatment adaptations, to tailor interventions to individuals with autism and anorexia nervosa.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper:

Babb, C., Brede, J., Jones, C. R. G., Elliott, M., Zanker, C., Tchanturia, K., Serpell, L., Mandy, W. & Fox, J. R. E. (2021). ‘It’s not that they don’t want to access the support. . .it’s the impact of the autism’: The experience of eating disorder services from the perspective of autistic women, parents and healthcare professionals. Autism, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361321991257

Other references

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. Doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brede, J., Babb, C., Jones, C., Elliott, M., Zanker, C., Tchanturia, K., Serpell, L., . . . & Mandy, W. (2020). “For me, the anorexia is just a symptom, and the cause is the autism”: Investigating restrictive eating disorders in autistic women. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 4280-4296. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04479-3

Kinnaird, E., Norton, C. & Tchanturia, K. (2017). Clinicians’ views on working with anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorder comorbidity: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 17. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1455-3

Lang, R., Regester, A., Lauderdale, S., Ashbaugh, K. & Haring, A. (2010). Treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders using cognitive behaviour therapy: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13, 53–63. Doi: 10.3109/17518420903236288

Leedham, A., Thompson, A. R., Smith, R. & Freeth, M. (2020). ‘I was exhausted trying to figure it out’: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism, 24, 135–146. Doi: 10.1177/1362361319853442

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Eating disorders: recognition and treatment. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69/resources/eating-disorders-recognition-and-treatment-pdf-1837582159813

Richardson, C. & Paslakis, G. (2021). Men’s experiences of eating disorder treatment: A qualitative systematic review of men-only studies. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28, 237-250. Doi: 10.1111/jpm.12670

Tchanturia, K., Dandil, Y., Li, Z., Smith, K., Leslie, M. & Byford, S. (2020). A novel approach for autism spectrum condition patients with eating disorders: Analysis of treatment cost-savings. European Eating Disorders Review, 29, 514-518. Doi: 10.1002/erv.2760

Treasure, J. (2013). Coherence and other autistic spectrum traits and eating disorders: Building from mechanism to treatment. The Birgit Olsson lecture. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 67, 38–42. Doi: 10.3109/08039488.2012.674554

Westwood, H., Eisler, I., Mandy, W., Leppanen, J., Treasure, J. & Tchanturia, K. (2016). Using the autism-spectrum quotient to measure autistic traits in anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 964–977. Doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2641-0

Westwood, H. & Tchanturia, K. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder in anorexia nervosa: An updated literature review. Current Psychiatry Reports,19, 1-10. Doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0791-9

Yao, S., Larsson, H., Norring, C., Birgegard, A., Lichtenstein, P., D’ Onofrio, B. M., Almqvist, C., . . . & Kuja-Halkola, R. (2019). Genetic and environmental contributions to diagnostic fluctuation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 51, 62-69. Doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002976

Photo credits

- Photo by averie woodard on Unsplash

- Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

- Photo by Kai Pilger on Unsplash

- Photo by JESHOOTS.COM on Unsplash

- Photo by Alex Blăjan on Unsplash

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash