How can you diagnose something if you don’t know the criteria for it no longer being there? Or to put it another way, if you can say what constitutes a diagnosis, surely a ‘non-diagnosis’ is the absence of these constituting features? Oh, if only life were that simple!

We all (hopefully) know that there is no such thing as normal, and that all of us sometimes have symptoms that would match up with one DSM-V diagnosis or another. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that we are mentally ill. By the same token, anyone who has experienced a mental health disorder is unlikely to live the rest of their life with absolutely none of the symptoms ever reoccurring.

These realities of experience are the backdrop for a recent systematic review, which explores the possibility of elucidating criteria to describe and define relapse, remission and recovery in anorexia nervosa (Khalsa et al, 2017). The primary aim for the authors was to find out how these three terms, in particular relapse, have been operationalised in the research literature. From their findings, the authors hoped to be in a position to suggest sets of criteria that future clinicians and researchers could consistently use to identify recovery, remission and relapse in anorexia nervosa.

We all experience the symptoms of mental illness from time to time, but that doesn’t mean we have a diagnosable condition.

Methods

Khalsa et al systematically reviewed English language peer-reviewed research papers that focused on recovery/relapse/remission and anorexia nervosa/eating disorders. 27 papers were identified from searches of PubMed, PsychInfo and Google Scholar for inclusion in their review.

Given this time period (1975-2016) and the broad inclusion criteria (people who met diagnostic criteria for anorexia), this seems like a surprisingly small number of papers.

Studies were quality-assessed using a checklist from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and whilst a range of quality was identified, no papers were excluded because of serious quality concerns.

Results

Khalsa et al had a secondary aim in their review: examining the reported relapse rates included in studies. This strikes me as highly illogical. Since the authors have based their work on the lack of a set of criteria for relapse in anorexia, how then can they possibly aim to report on relapse rates? All they can really do is report on figures that fit individual relapse criteria specific to each research study; presenting these as a range of relapse rates undermines the expressed need for a shared set of relapse criteria. Unsurprisingly, they found a relapse rate range of 9-52%, but this ‘relapse rate’, to me, is not actually representative of any one clear thing, except that eating disorders can be very difficult to overcome in the longer term.

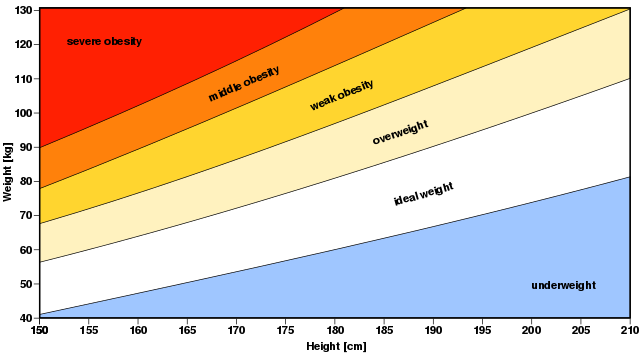

In terms of the primary aim, the authors identified that most studies defined all three terms by weight and/or reported symptoms. The use of weight or body-mass index (BMI) as a marker for anorexia nervosa recovery is not without critics, especially amongst those who have experienced anorexia; it surprised me to see in the summary tables provided in the paper that some studies published within the last few years were using only BMI to define relapse or recovery. The summary tables are an enlightening feature of this review, capturing not only what each study has used as parameters for recovery and/or relapse, but also, because the papers are listed in chronological order, capturing the lack of any trend or consistent shift in our understanding of anorexia recovery and relapse over the last forty years.

The review highlights that many anorexia nervosa studies published in recent years only use BMI to define relapse or recovery. A practice now widely frowned upon by patients and clinicians.

Conclusions

The authors then move on to present their own definitions of recovery, remission and relapse. They break each of these down into ‘full’ and ‘partial’ categories by time duration; giving a sort of six-phase spectrum of anorexia status. Relapse is identified by BMI at or below 18.5, significant weight gain fears, eating disorder behaviours being present (restricting/bingeing/purging) and a score on the Eating Disorders Examination (EDE) two standard deviations over the ‘normal’ marker. At the other end of the spectrum, full recovery is given as a 12 month duration with BMI at or over 20, no body image or weight gain disturbance, no eating disorder behaviours present and EDE score within one standard deviation of normal.

Implications for practice

The logic of a range of markers for relapse, remission and recovery is clear, and the authors point out some of the benefits of their system over what currently exists, such as providing guidance for full and partial recovery and timeframes for these, which the DSM-V lacks. However, most of the benefits seem to be for researchers rather than clinicians, as the spectrum of definitions clearly lends itself to longitudinal work.

Yet one can see a future in which care across the various tiers or steps of the health care service could support people with eating disorders by having a shared set of monitoring criteria and a spectrum where it would be clear when an increase or decrease in support level was appropriate. One can imagine that this might provide some security for people with anorexia to know that discharge from a support service would not be the apparent end of the line of care, as often seems to be the case.

Discharge from support services is the beginning of a tough journey for many people living with eating disorders.

Strengths and limitations

Something that seems to be missing here, as things stand, is any test of the face validity of the definitions with people living with anorexia, or with clinicians working in eating disorder services. This could be a very valuable next step in taking this work forwards, and a good way to start engaging the eating disorders community in the work.

However, there’s a smack here of: “but maybe we will be the exception to the rule”. As the authors report, a consensus group of European experts drew up and tested out criteria for relapse, recovery and remission 15 years ago, to no avail (Kordy et al, 2002). There’s no apparent thinking through about why they failed to get any traction in research or clinical work, or consideration as to why the current study will succeed despite this warning from history. More broadly, one of the things the summary tables in the paper makes clear is that there has been no apparent willingness amongst researchers to find a consensus over a considerable period of time. What, then, would be the incentive now? Or, more positively, how could researchers feel energised to engage with Khalsa et al’s definitions?

Furthermore, in terms of clinical application, there’s an operational question raised here about how definitions come to be adopted widely enough to go past a tipping point. In terms of clinical work, unless such guidelines get significant policy backing, it is unlikely that they will challenge the might of the DSM and ICD. This is perhaps one of the key differences, at this point, between this work on anorexia and the recovery and relapse definitions that are already in existence for other mental health difficulties.

All this serves to illustrate the massive challenge of getting traction and disseminating purposefully from clinical research. This is not to decry the work of Khalsa et al, but one suspects that their efforts will not garner the attention they might deserve.

What do people living with anorexia nervosa and the clinicians who care for them think of this work? Surely that’s the acid test.

Links

Primary paper

Other references

Kordy H, Kramer B, Palmer RL, Papezova H, Pellet J, Richard M, et al. (2002) Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence in eating disorders: Conceptualization and illustration of a validation strategy. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(7):833–46. [PubMed abstract]

Photo credits

- Seth Werkheiser CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Jeremy Wong on Unsplash

- By me (Own work. Image renamed from Image:BMI.svg) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

- Photo by Braden Hopkins on Unsplash

- Tim Green CC BY 2.0

This is a very sensitive and personal matter, so I applaud you for tackling this subject and studying it; hopefully this study can make a positive impact on the lives of many people who suffer from eating disorders