Many friends, family and professionals supporting people with learning disabilities are keen to help people adapt to different social situations. With a key feature of learning disability being a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and learn new skills, (DoH, 2001) it is reasonable that some structured support may be needed for many learning disabled people.

A project in the Republic of Ireland identified that learning disabled people can find it difficult to learn social rules and behaviours, and that this has become more important to address with increasing expectations that everyone will be part of their community. (N.B. the terminology used within the source article is ‘people with intellectual disabilities).

The Safe and Social programme was implemented within a single organisation in Ireland, which has a range of services including residential, day services, transport and residential respite; so will include some learning disabled people living outside of the service. The authors come from a variety of backgrounds: academic, speech & language therapy and social work.

The programme was devised to help the service’s users to learn the reasons why some social behaviours are desirable or not, and why this varies in different contexts and with different people.

The aim was to move from people being told not to do things because of service or individual staff’s ‘rules’, and instead to understand why they were being encouraged to change and therefore embed what they learnt and be able to transfer to other situations.

The background information focuses on society’s mixed attitudes to disability and some of the issues faced by the people the service support e.g. believing a relationship with a staff is a friendship; or that a friendly stranger at a bus stop is therefore a friend. There is acknowledgement that communication skills are an integral factor interacting with social competence.

One of the largest studies cited by the authors is the meta-analysis by Kavale & Forness (1996) which looked at 152 other studies of the area and concludes 75% of learning disabled people have deficits in their social skills. This study is now almost twenty years old but probably remains the most wide-ranging review.

Supporting people to learn about being in different social situations using group discussions

While it is clear that many learning disabled people can benefit from thoughtful, structured support which assists them to improve these skills, (and in turn their personal safety) Reiff’s caution against generalisations is also refreshing, as many learning disabled people’s social skills are “a significant compensation and a key to success”, chiming with my own experience of meeting many learning disabled people who are charming, entertaining, gregarious and sociable. A deficit model does not always tell us everything we might wish to know about a person.

Method

The programme is run by discussion group sessions which progress at the service users’ pace through several topic areas, including relationships, behaviours, body parts, private and public places, saying ‘no’, and being safe.

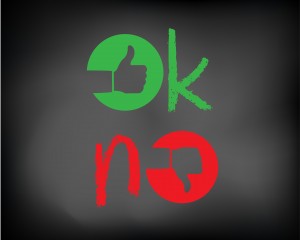

The difference in the programme implemented by the authors to previous structured programmes of support is that it is deliberately much simpler, using red/’not OK’ and green/’it is OK’ terminology and both visual and verbal methods of teaching, to include people with different levels of literacy and verbal abilities.

Participants placed picture symbols on the red or green circle depending on how they perceived the behaviour under discussion.

The training has been provided to 120 adults with learning disabilities and 46 staff. Currently there has been no systematic evaluation of the results for this cohort. Checklists are now being used to obtain a baseline measure from which to assess progress.

Findings

The authors describe more able participants as able to bring their own experiences into group environment for problem-solving; and most participants benefitted from the framework and simplicity of the red/green system.

So far the outcomes remain anecdotal from participants and their support staff, but the programme has provided a welcome tool that can be used in different environments; with many participants improving their ability to describe appropriate behaviours in different situations; and put this into practice with the ongoing support of their staff away from the group.

As recognised by the authors, the ongoing support of other staff is essential to the participants so they can continue to use skills beyond the structured group setting. This would also help avoid any tendency to see speech and language professionals as ‘experts’ and that communication/social skills support can simply be left solely the responsibility of the group programme.

The project used visual methods of learning

Strengths & Limitations

The professional speech and language background of some of the people devising and running this programme is apparent in the total communication approach used, with visual tools. This was likely to be a key benefit, given that support staff routinely over-estimate learning disabled people’s ability to understand verbal language (Purcell, Morris & McConkey 1999, cited in Cambridge & Carnaby, 2005).

However, it is not clear how the visual tools were (or could continue to be) utilised when trying to support participants to generalise what they had learnt into their everyday lives, away from the structured group setting. Some people with learning disabilities could benefit from using the same tools wherever they go and others may feel self-conscious.

The introduction of a method for measurement of progress will be essential to advocate for the continuation of this programme in a time of belt-tightening for publicly-funded services, and could also be useful in gaining insight about how the programme is effective (or otherwise) for people with different characteristics, for example males/females, younger/older participants, or with different levels of verbal skills.

Some independent scrutiny of this process may benefit the project to avoid any unintentional bias towards positive outcome measurements. This evidence would need to be gathered and analysed before the programme could be more widely shared and used by others.

As social behaviour is often culture-specific, additional thought would be needed when talking about what is ‘OK’ and ‘not OK’ when working with participants who are not from a homogenous cultural background (Olmeda & Trent, 2003).

The group basis for learning may have been a limitation for some participants, given the wide variation in individual learning styles and abilities. The topic of social skills may lend itself well to group discussions, but this is unlikely to meet everybody’s needs.

The authors state that people can choose to have individual support on request, but the reality of many group-based service cultures and resource constraints may mean that this is not actively encouraged or even fully understood to be an option by potential participants.

It would have been interesting to have more information about the breakdown of where participants live, as I was interested in how much support people got with practising the skills learnt when they were not at ‘the service’.

In particular, a large proportion (38%) of learning disabled people remain living with family or friends (Mencap, 2011). In my experience many family carers value the input of speech and language professionals but much more work is required to understand if the Safe and Social programme is one that would be welcomed and further facilitated by family carers.

There is a need for a consistent assessment method to measure progress and build evidence

Link

Forde, J., G, Flanagan, L., Hone, L., Smith, M. and Tinney, G.(2014) Safe and social: what does it mean anyway?? British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43, 55–61 [abstract]

References

Cambridge, S. & Carnaby, P. 2005 Person Centred Planning And Care Management with People with Learning Disabilities Jessica Kingsley: London

Kavale K. & Forness S. (1996) Social skill deficits and learning disabilities: a meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disability, 29: 226–37 http://ldx.sagepub.com/content/29/3/226.abstract

Mencap (2011) Housing for People with a Learning Disability https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2012.108%20Housing%20report_V7.pdf

Olmeda, R.E. & Trent, S.C. (2003). Social skills training research with minority students with 4 learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities, 12(1), 23-33. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ666155

Reiff, H. (2015) Social Skills and Adults with Learning Disabilities

Linkages Vol. 2, No. 2 National Adult Literacy and Learning Disabilities Center, Washington, Charles W. Ed http://www.ldonline.org/article/6010/

Valuing People, Department of Health (2001) Valuing people: a new strategy for learning disability for the 21st century. London: The Department.

Today @mandylou26 has published her debut blog on helping learning disabled people improve skills and understanding http://t.co/gi6ypVtCKF

Supporting people with LD to learn about being in different social situations using group discussions http://t.co/gi6ypVtCKF

Thank you for your very useful comments and your concise summary. One quick correction – this work was carried out in the Republic of Ireland (which also explains perhaps why the term intellectual disability was used). We have since started evaluating the perceived impact of the intervention from the point of view of families (through focus group discussions) as well as care staff involved in this service and continue to roll out the assessment protocol. The key goal is to develop a shared language to discuss issues of safety in social contexts, so that service users have access to a common way of describing and interpreting behaviour as they move across contexts in their daily lives. Many of the service users live at home, others live in a range of supported accommodation environments. The needs are sometimes different across these contexts. So – some work done, a lot more to do, but it has been a very interesting journey so far!

Hi Martine,

thanks for your comment. Our aim with the Leaning Disabilities Elf site is to produce concise and usable summaries of research and the site is aimed mainly at professionals in the field.

Good to hear that the project continues and that further evaluative work is underway and of course, there is always more work to be done!

Apologies for our error over where the project took place. I have corrected that in the text,

john

Martine, thanks so much for taking time to reply. Many apologies about noting the location of the study wrongly, this has now been rectified by John.

It’s exciting that you have been able to continue evaluating and I look forward to hearing more about how families are getting involved to support people too. Good luck with the work in the future, it is an important area.

Regards

Mandy

Don’t miss: Safe and social – helping learning disabled people improve skills and understanding http://t.co/gi6ypVtCKF #EBP

Safe and social – helping learning disabled people improve skills and understanding – The Learning Disabilities Elf http://t.co/M7ah3c3srd

Hello, Mandy Johnson.

I was just wondering whether it would be possible to get a copy of your group programme?

I have tried to find your contact details to email you directly but cant find them online.

Carly

I have been trying to find a job doing this. All I can find is residential jobs for people with severe learning difficulties but doing stuff like changing pads is not something I can do.

I did it once before in a SEC which was a day centre. I loved it but unfortunately, it was only a voluntary position and I needed a job that paid so I could pay my bills etc.