Supervision is a requirement for all practicing psychotherapists in the UK (UKCP, 2012). Supervision aims to develop a clinician’s practice, by providing a reflective space to consider their own strengths and difficulties, including how they relate to clients. A necessary area to consider in sessions is the way in which other people and situations are perceived, and this is shaped by a person’s own background and experience.

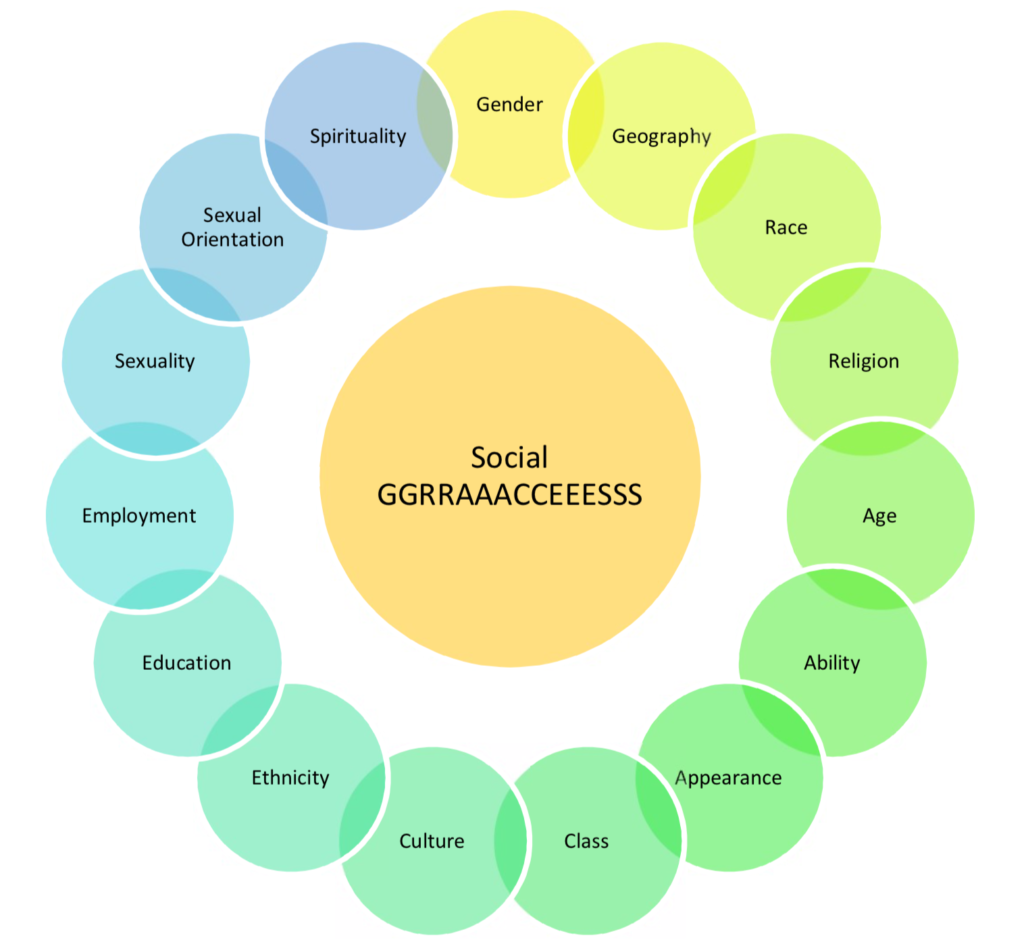

A paper considers whether social GGRRAAACCEEESSS (no, not a typo, but an acronym) provides a suitable framework for supervisors to structure their sessions, through which therapists can reflect on their own beliefs and prejudices in order to understand how they might bring these into the therapy room (Totsuka, 2014).

Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS (SG) is an acronym that stands for the above aspects of a person’s identity.

Methods

- 3 trainee family therapists, in group supervision facilitated by the author:

- Ruth: a British-born, Jewish woman

- Patrick: a White, Australian gay man

- Ellen: a Black, African woman

- In a supervision session, participants were asked to choose 2 elements of social GGRRAAACCEEESSS (SG) that “grabbed” them and 2 that did not

- They were then asked to describe significant personal experiences that related to those aspects

- Reflections were then offered by those observing.

Results

The author described the following:

- “Powerful experience”: the participants found that they strongly connected to elements of SG, and that the sharing of personal stories from others helped explain why those elements held such influence for them, e.g. Ellen felt strongly connected to race, and shared that growing up black in Zimbabwe under segregation and a white ruling minority meant that she tended to see race as most relevant to her life experiences.

- Interconnectedness of SG elements: the participants found it difficult to disentangle elements from each other, e.g. Ruth could not separate her understanding of her Judaism from ethnicity, religion and culture.

- “Visible/invisible”: participants found that some aspects of SG can be chosen to be voiced or remain invisible, e.g. Patrick shared that he chose to ‘voice’ his sexuality in job interviews as he did not want a job in a homophobic environment.

- Change over time: participants said that elements had more or less influence depending on time and context, and that elements were always moving in and out of the foreground.

- “Non-grabbing aspects”: participants explored why certain aspects did not grab them, and suggested it may be either due to lack of experience (e.g. disability) or deliberate avoidance (e.g. Patrick distanced himself from religion due to negative childhood experiences related to his sexuality).

The family therapists who participated in this research were able to use Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS to consider aspects of their identity and experiences.

Conclusions

The author concluded that the experiential process of exploring Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS was a powerful learning tool, which increased supervisees’ curiosity in both themselves and others. The use of the exercise within a group supervision setting was particularly helpful as it presented multiple experiences, which allowed for the participants to reflect on their similarities and differences.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- This study provided rich information about the experiences of the 3 participants involved, and demonstrated how each person connects to the aspects in a personal way

- As a framework, SG pushes participants to consider their relationship to all the aspects, even the ones that don’t grab them, and to consider why it doesn’t grab them and whether it’s something they are ‘blind’ to.

Limitations

- It is unclear whether it made an impact on the participants’ practice. The author states that enhancing supervisees’ self-reflection on their assumptions and beliefs would be beneficial to their clients but does not provide any examples of how the participants used the experience in their practice:

- Did they take the experience into the therapy room with them?

- Did it make them consider a client’s experience in a different way?

- Did they find themselves reflecting on previous interactions with clients and seeing things from an alternative view?

Whilst the therapists who participated enjoyed the experience, the author did not follow up to see if it affected their practice.

Implications for practice

- The suggestions in this paper could be extended to provide a manual to supervisors on how to use Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS in supervision sessions, detailing issues such as how often to use it, how to set the conversation up correctly etc. As the author mentioned, upon reflection she wondered whether her joining in on the activity was entirely appropriate, and a manual could discuss the ways in which this could be appropriate.

- SG could also be used as the first step in supervision towards considering cultural differences, with focus moving from raising awareness of difference towards skill building to develop culturally relevant therapeutic strategies.

- The questions asked about SG could go further by borrowing a concept from feminist and race theory called intersectionality. Intersectionality looks at how aspects described in SG interconnect and consider how these combinations can produce unique experiences (Butler, 2015). For example, Ellen will have different experiences of race compared to a black man and different experiences of gender compared to a white woman as she experiences life as a black woman. Intersectionality considers the interplay of SG aspects, and how the sum is greater than its parts. Supervision sessions would benefit from considering ideas of intersectionality when looking at SG, as it forces participants to think about the aspects in a more nuanced way.

The exercise could be extended to consider intersectionality; the interplay between aspects within the Social GGRRAAACCEEESSS model.

King’s MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a student on the Mental Health Studies MSc at King’s College London. A full list of blogs by King’s MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Totsuka, Y. (2014). ‘Which aspects of social GGRRAAACCEEESSS grab you most?’ The social GGRRAAACCEEESSS exercise for a supervision group to promote therapists’ self-reflexivity. Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 106. 10.1111/1467-6427.12026 [Abstract]

Other references

Butler, C. (2015). Intersectionality in family therapy training: inviting students to embrace the complexities of lived experience. Journal of Family Therapy, 37(4), 583-589

UK Council for Psychotherapy (2012). UKCP Supervision Policy.

Photo credits

- Photo by loli Clement on Unsplash

- Photo by Kyle Glenn on Unsplash

- Photo by Katie Moum on Unsplash

- Spaynton [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

3 trainee family therapists, in group supervision facilitated by the author:

Ruth: a British-born, Jewish woman

Patrick: a White, Australian gay man

Ellen: a Black, African woman (AFRICA IS NOT A COUNTRY) Ironic that an article on Social Grrracccceees would omit to put Zimbabwean on Ellen’s profile. This makes me so ANGRY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Hi Alex, I was excited to see your article about the Social GgRRAAAACCEEESSSS….S (Burnham, J. 1992, 2012, 2020, Roper-Hall 1998) I am in the process of making a workbook on the Social GgRRAAAACCEEESSSS….S and would like to include some of your work in it. I don’t have an email to contact you.