This recent paper by Priebe and colleagues (2016) provides follow-up data from an original trial which explored the impact of paying service users to receive their depot of long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI).

The original study can be found here, or if you prefer you can read my Mental Elf blog which discusses the findings.

The previous study randomised service users into two groups paying one group £15 for each depot injection they received over a 12-month period. The other group received treatment as usual (i.e. no financial incentives).

There have been a number of similar studies across a range of disorders internationally for example in tuberculosis and HIV. Rarely have they followed-up study participants after the trial to see if benefits are sustained, but this was the aim of Preibe et al (2016) study. The original study lasted 12 months and this new paper followed-up the patients for a further year to see how well people had adhered to their medication without any further financial incentives.

The previously published RCT concluded that offering small financial payments improved adherence to depot antipsychotics after 12 months.

Methods

The study only included patients who wanted to take their medication, rather than those who didn’t want to. The intervention group received an additional £15 per injection, which they stopped getting after 12 months. A large number of clinical teams were recruited, these were stratified before block randomisation.

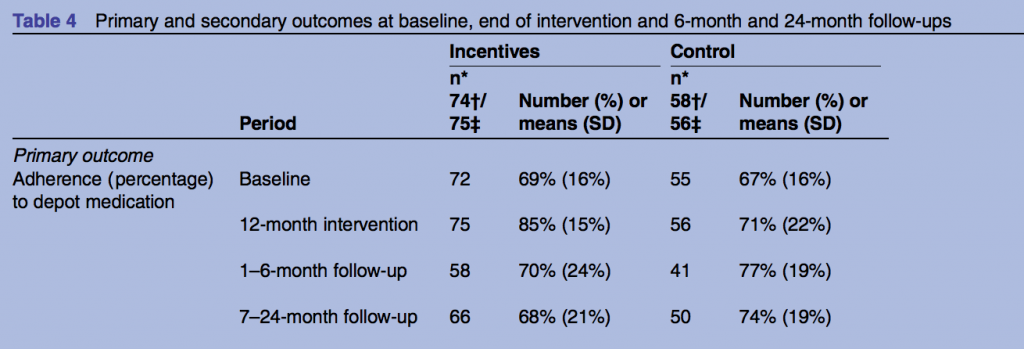

Both groups from the original trial were followed up at 6, 12 and 24 months. The same outcome measures from the previous study were used. The primary outcome was the percentage of depot injections given during the follow up period. Secondary outcomes included percentage of adherence >95%, clinical symptoms and quality of life.

Results

- At 6 months, adherence was 77% in the control group and 70% in the intervention group who received the financial incentives (Adjusted Means Difference (AMD) −7.4%, 95% CI −17.0 to 2.1, p=0.175). At this point the incentives group did slightly worse than the control group although this result is not statistically significant.

- At 12 months, adherence was 71% in the control group and 85% in the intervention group (AMD 11.5%, 95% CI 3.9% to 19.0%, p=0.0003). The financial incentives had a statistically significant effect at this stage, which is why the first publication had a positive conclusion.

- However, at 24 months (12 months after the last £15 payment), adherence was 74% in the control group and only 68% in the intervention group (AMD −5.7%, 95% CI −13.1% to 1.7%, p=0.130). The incentives group did worse than the control group, but it’s important to stress that this result is not statistically significant.

- There were no statistical differences in secondary outcomes of admissions, violence incidents, suicide attempts or police arrests.

- There was a higher number of hospital admissions in the intervention group at 6-months and 24-months.

Authors conclusion

The authors concluded:

It may be concluded that incentives to improve adherence to antipsychotic maintenance medication are effective for as long as they are provided. Once they are stopped, adherence returns to approximately baseline levels with no sustained benefit.

&

Adherence levels in the intervention group were even lower than in the control group, but the differences are small and not statistically significant.

This trial found no statistically significant difference in adherence between the control and intervention groups at 2 year follow-up.

Strengths and limitations

As with the previous paper, there is limited detail on the type and dosage of medication, and whether this was switched during or after the trial. Clearly there was variation in the frequency and doses of injections received, and a better understanding of this might add further to our understanding of why some people adhered to treatment and others did not. The authors suggest that a longer time between injections increased adherence, this was the case in the control group which might help explain the findings. Adding in a follow-up interview with service users about why they stopped with the depot would have added useful additional information.

It was good to see a study that provided a long follow-up period post trial and one which was able to maintain a reasonable follow-up period. A major concern of most drug trials is the very short duration of follow-up. However, there was a concern that as time progressed drop-outs and missing data increased, this could potentially have increased the bias in the study. This is particularly worrying if the drop-outs were different from those who remained in the study, for example, those who lost contact with mental health services completely.

Implications

This study shows that financial incentives may well increase treatment adherence in people with schizophrenia receiving depot antipsychotic injections, but for many services users this adherence may only continue until the payments stop. The benefits of adhering to treatment were not covered in this study, but other research suggests that a consistent period of medication may lead to reduced relapse, increased social function and stability for patients.

However, this new evidence also suggests a risk or trend that if you stop paying people to receive injections they might be more likely to stop taking the medication than if you hadn’t paid them in the first place. The risk of relapse associated with stopping medication is clear and this is a potentially important finding for future researchers and policy makers.

Financial incentives: only effective as long as they continue?

Links

Primary paper

Priebe S, Bremner S, Pavlickova H (2016) Discontinuing financial incentives for adherence to antipsychotic depot medication: long-term outcomes of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open;6:e01 1673. Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011673

Other references

Priebe, S. et al Effectiveness of financial incentives to improve adherence to maintenance treatment with antipsychotics: cluster randomised controlled trial BMJ 2013;347:f5847 (Open Access paper featuring a video interview with the lead author Stefan Priebe).

Kendall, T. Paying patients with psychosis to improve adherence (editorial). BMJ 2013;347:f5782

RT @Mental_Elf: Today @JohnBaker_Leeds on discontinuing financial incentives for adherence to antipsychotic depot medication https://t.co/2…

Morning @QMULSocialPsych @stephenabremner We’ve blogged about your @BMJ_Open RCT on financial incentives https://t.co/27LRRuMsN7 Thoughts?

RT @JohnBaker_Leeds: Today’s @Mental_Elf blog on what happens if you stop paying service users to have their depot https://t.co/m6llR6X1l2

Financial incentives to take antipsychotic medication

Only effective as long as they continue?… https://t.co/SvthBQcxt1

@Mental_Elf Makes you wonder why patients aren’t convinced by the effectiveness of the treatment.

.@Mental_Elf V interesting. Raises ethics Qs re: power dynamics in medication compliance. Esp if you see Sz as trauma reaction not “disease”

Study suggests that paying for injections needs psychological treatment for long term effects https://t.co/pxCU1FRLkt via @sharethis

https://t.co/oH4D3GhjKs. paying service users to receive their depot of long-acting injectable #antipsychotic @JR_MerseyCare @RayFWalker

Don’t miss:

Depot antipsychotics

If you pay me, you can keep injecting me

https://t.co/27LRRuMsN7 https://t.co/zcjEelYUOg

Last call for today’s @Mental_Elf blog what happens when you stop paying people to take antipsychotic medication https://t.co/qcQWRxVmlP

@JohnBaker_Leeds @Mental_Elf Issues with power, not accounting for trauma, and that reduction in intrinsic motivation is predictable. Poor.

Interesting

The official summary of yesterday’s @Mental_Elf blog on what happens when you stop pay people to take antipsychotic… https://t.co/nRE7nI3I39

Highly recommended:

Depot antipsychotics: If you pay me, you can keep injecting me

https://t.co/6dAFDlh9Qb

via @Mental_Elf

@Doc_Murtada @Mental_Elf so you can’t even pay people to take their medicines! It is all down to cognition.

@TheMMP1 not exactly, payments increased adherence as long as payments continued

@Mental_Elf

@TheMMP1 dont forget, this was in a psychiatric pt group with depot injections, not sure if applicable to pts who take pills..

@Mental_Elf

Depot antipsychotics: If you pay me, you can keep injecting me https://t.co/Re3i7qxE2u https://t.co/qTrmFWE6oQ

Depot antipsychotics: If you pay me, you can keep injecting me https://t.co/kVT31E6JPz

https://t.co/oH4D3GhjKs. Paying #mental health patients for depot injection ! Is it ethical ? @BeresfordPeter @asifamhp #psychiatry Pls RT

[…] This growing interest in communication in clinical encounters has been recognised on the The Mental Elf before, notably in two recent blogs by John Baker about related papers on communication with those with psychosis, and financial incentives for treatment concordance. […]

Hi I am Jiří Z., from Czech republic and I am psychiatric nurse on acute ward, I would like to speak with acute psychiatric nurse from abroad. I would like to find out how do you do nursing and if you want, I tell you about our backward nursing here.