Perinatal mental health is a major public health issue. A recent economic report estimated that perinatal mental health disorders carry a total long-term cost to society of £8.1 billion for each one-year cohort of births in the UK, with around 70% of these costs being borne by the adverse outcomes for the child (Bauer et al., 2014).

A better understanding of the risk factors, triggers and maintaining processes for these disorders can help to develop effective interventions, as well as potential preventative measures, in order to reduce the burden of perinatal mental health both on families and on wider society.

Most research has focused on depression and it is estimated that around 1 in 10 women suffer from depression in the perinatal period. This not only affects the wellbeing of the mother, but also impacts on the developing relationship with the baby. Longitudinal studies have shown poor outcomes for the children of mothers with perinatal depression throughout childhood and adolescence (Stein et al, 2014).

A key mechanism by which depression is thought to impact on the infant is through its effect on parenting behaviours, in particular, though reduced maternal sensitivity and responsiveness to infant cues. What is it about depression that makes a mother less sensitive in this way? One possibility is through cognitive processes such as rumination, worry or obsessions, which take up attentional resources and make it hard for a mother to accurately notice and respond to her baby’s signals. Understanding these processes better may help to develop targets for intervention and therefore reduce the impact of depression on the child.

Rumination is a key cognitive feature of depression and is defined as:

A mode of responding to distress that involves repetitively and passively focusing on the symptoms of distress and the possible causes and consequences of these symptoms.

– Nolen-Hoeksema et al, 2008.

The aim of this paper was to provide a systematic literature review of evidence relating to rumination in the perinatal period, specifically its links to depression and its potential impact on parenting behaviours. Based on this the authors present a new cognitive model of the impact of rumination in the perinatal context with the aim of guiding future research in this area.

Cognitive processes such as rumination, worry or obsessions may make it hard for a mother to accurately notice and respond to her baby’s signals.

Methods

The authors used the PRISMA guidelines for their review, searching a number of key databases as well references and citations of identified papers, using search terms that included phrases used to describe perinatal depression and rumination. Papers had to have data related to the perinatal period (conception to 12 months), report data on a measure of rumination and be published in a peer reviewed journal.

After duplicates were removed and full texts were screened for inclusion criteria, ten papers were identified. Eight of these used questionnaire measures to examine links between rumination and specific outcomes, including depression and bonding. The other two papers used an experimental design to look at the effect of induced rumination on parenting behaviour.

Results of the review

Overall the results provide mixed and limited evidence about whether rumination predicts postnatal depression, particularly when taking into account other variables such as previous episodes of depression or social support. Similarly, evidence of the association between rumination and bonding is limited by the very small number of studies. However, the two experimental studies suggest that inducing rumination has an impact on maternal responsiveness and infant-related problem solving in clinical samples.

The reviewers conclude that:

…there is some information about the potential role of rumination in predicting later outcomes, including maternal depression and mother-infant bonding. There is also some initial evidence that rumination plays a causal role in impairing parenting quality in clinical populations. However, there are many remaining questions and areas where this work could be extended.

The authors go on to highlight that the literature in this area lacks a theoretical or organising framework, and they present a new cognitive model, informed by the review and by existing theories of rumination, to account for the effects of rumination in the postnatal context.

A cognitive model of rumination in the perinatal period

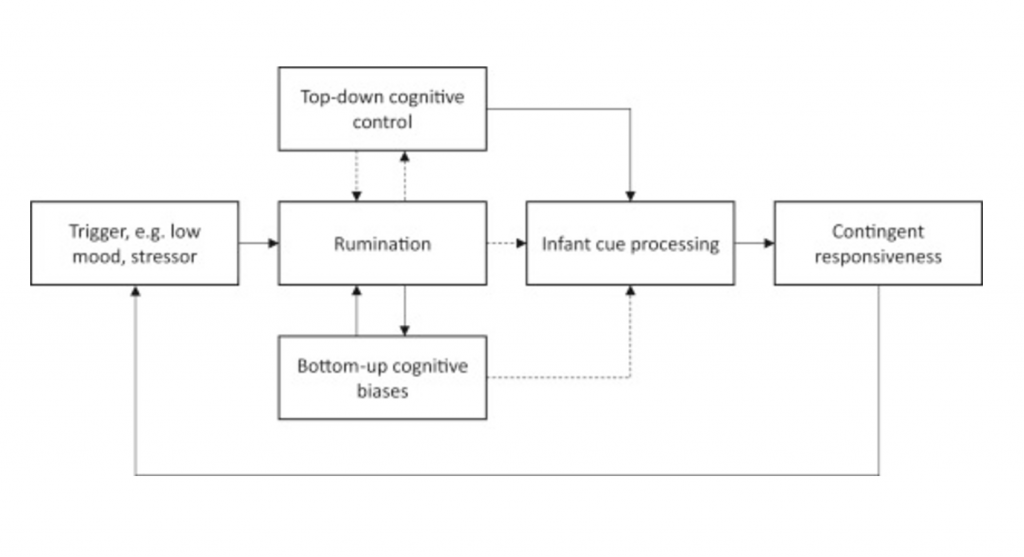

In developing the model, the authors focus on two key cognitive processes which have been implicated in the literature on rumination. These are cognitive control and cognitive biases.

Cognitive control

Cognitive control refers to the ability to think flexibly, for example, switching attention and ignoring irrelevant information when focusing on a goal. Poor cognitive control has been linked to the onset and maintenance of rumination in depression. This would be important in the postnatal period as parenting requires a high level of attention and puts heavy demands on executive functions.

Cognitive biases

Cognitive biases in this context refer to attention to and interpretation of emotional facial expressions. People with depression tend to pay more attention to negative expressions and are more likely to interpret neutral expressions as negative. In the postnatal period the interpretation of infant emotional expression is biased, which affects appropriate and contingent responding of infant cues.

Within the model these two processes are proposed to have bidirectional links with rumination. Therefore, following an initial trigger or stressor rumination is established and maintained through deficits in these two processes. This then affects infant cue processing due to problems with attentional resources, attentional bias and negative interpretation of infant stimuli. This leads to poor responsiveness, which may affect the mood and emotional regulation of the infant, leading to further triggers/stressors for continued rumination.

The authors discuss the implications for practice as well as possible directions for future research. They review evidence that CBT may not reduce rumination and that other approaches such as mindfulness and acceptance-based therapies, which specifically target rumination, may be more effective both at reducing this aspect of depressive cognition and also at preventing relapse in depression. In addition, they discuss how the model generates testable predictions about the possibility of using attention bias modification techniques to target bottom-up cognitive biases, or executive function training to target top-down cognitive control deficits, in order to improve sensitive responding.

Figure 2 reproduced from Dejong et al, 2016: Information processing model of rumination and effects on parenting behaviour. Solid lines indicate positive links and dotted lines indicate negative/inhibitory links.

Conclusions

The authors conclude:

The theoretical framework outlined here may have utility in guiding future research and in the development of improved interventions in PND [postnatal depression]. It provides a theoretical account of potential maintenance mechanisms and suggests several pathways that may be modifiable.

Strengths and limitations

As the authors note, there are few studies in the review and they have mixed designs, which limits the conclusions. Also, several studies include self-report questionnaires which can be problematic as depression may impact on ratings of mother-infant bonding.

While the search terms included ‘depression’, it’s not clear how depression was identified i.e. if a clinical diagnosis was included in the studies or just a screen. The term depression often gets used in the perinatal period to include a range of presentations, including anxiety and trauma reactions, and screening measures for depression may pick up these other difficulties. The authors note that many cognitive processes such as rumination tend to be transdiagnostic, and therefore, perhaps a more general model of the impact of rumination on parenting behaviour in the context of perinatal distress may be more representative of the women that this would apply to.

The paper doesn’t include a discussion of the methodological quality of the studies or the effect sizes. As these studies are used as a basis for the cognitive model this seems to be an important factor which would have been useful to include.

In terms of the model, this is well described and detailed and draws both from the wider literature on rumination and depression as well as the review that the authors completed. It suggests targets for intervention as well as areas for further research and development. This is a useful addition to the developing understanding of perinatal disorders and their impact on the mother-infant relationship.

Risk factors for maternal depression

These potentially modifiable cognitive processes that can maintain depression and affect sensitive responding are important to be aware of when assessing and treating perinatal disorders. However, from both my clinical experience and the literature on risk for depression, it is important that we keep in mind the full range of risk factors for maternal depression when thinking about prevention and intervention. In particular:

- The couple relationship is a major factor in both triggering and maintaining depression. An unsupportive, critical, or abusive partner can have enormous implications for a woman’s mood and her ability to provide responsive care for her baby. A focus on her own cognitive processes without taking this into account can risk putting the burden for change on an already exhausted and overwhelmed mother, where in fact the change needs to happen within the relationships around her.

- The common narratives around motherhood, particularly the expectation to manage without support and not to show weakness or complain, are unhelpful and unrealistic and can increase the gap between expectations and reality, which acts as an important trigger for perinatal depression and anxiety. Shifting these narratives may help to reduce the stressors that can trigger and maintain rumination.

- Finally, a discussion about depressed mood in the postnatal period is not complete without a mention of the key role that sleep plays. Sleep deprivation not only affects mood but also affects the cognitive processes described in the model, impacting on executive functioning and attention. Therefore, improving sleep through increased social support or sleep hygiene education can have a major effect on mood and functioning.

Keeping in mind the many factors that contribute to the onset and maintenance of perinatal distress, including biological, cognitive, emotional, social and cultural factors, may be clinically challenging, but it is also essential if we are to provide effective interventions for families. This paper makes an interesting and important contribution to the cognitive level of understanding of perinatal difficulties.

It’s vital that we see the full picture when considering how best to help and support women experiencing perinatal distress.

Links

Primary paper

DeJong H, Fox E, Stein A. (2016) Rumination and postnatal depression: A systematic review and a cognitive model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, Volume 82, July 2016, Pages 38-49, ISSN 0005-7967 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.05.003.

Other references

Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, Iemmi V, Adelaja B. (2014) Costs of Perinatal Mental Health Problems. London School of Economics and Political Science, 2014.

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. (2008) Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400e424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum & Pariente (2014) Effects of perinatal mental health disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 384(9956), 1800-1819. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0

Do perinatal mental health problems cost the UK £8 billion per year?

Rumination and postnatal depression: a systematic review and cognitive model https://t.co/plMdTSXdrq

Rumination and postnatal depression:

A systematic review and cognitive model

https://t.co/JMsnNGBZUS https://t.co/DPME02Eq2k

Today @jilldomoney on perinatal MH review, which includes a new cognitive model of rumination & postnatal depression https://t.co/JMsnNGBZUS

Welcome to the woodland @jilldomoney That’s an absolute belter of a debut blog!! https://t.co/JMsnNGBZUS Hope you’re up for writing more..?

Rumination and postnatal depression: a systematic review and cognitive model – from @Mental_Elf https://t.co/gOotIWt7xR

Rumination and postnatal depression: systematic review & cognitive model https://t.co/yaHK35Xfli https://t.co/qMjfoOcHVI

RT @Mental_Elf: It’s vital we see the full picture when considering how best to help & support women experiencing perinatal distress https:…

Rumination and postnatal depression:

A systematic review and cognitive model

https://t.co/JMsnNGBZUS https://t.co/ySkh0HZ1IU

#Ιδεομηρυκασμός και #επιλόχειος #κατάθλιψη. Ένα #γνωσιακό #συμπεριφορικό μοντέλο.

https://t.co/kt5sIgIMRB