For much of the last century, research on parenting and child development has centred on mothers. This focus is perhaps unsurprising, given the greater amount of time that mothers spend caring for their children, as well as society’s perceptions about the importance of mothers versus fathers in children’s nurture.

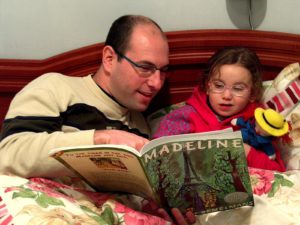

However, these days, the experience and views of fatherhood are undergoing a change. Today’s dads-to-be are able to attend pre-natal and parenting classes, they are taking paternity leave, and some of them are opting to stay home to care for their offspring. Many of today’s fathers are taking on a more active role in child caring, with fathers now spending about 59 minutes a day caring for their children; much more than what the average father used to 50 years ago (Dotti Sani & Treas, 2016).

Alongside this increasing involvement of dads in their children’s lives, there has also been a shift in child development research, toward a greater inclusion of fathers. A recent review and commentary by Barker, Iles and Ramchandani summarises a set of studies addressing a particularly important issue: how fathers and fathering may shape the development of child psychopathology. Child mental health problems are common, but their aetiology is poorly understood. Researching the influence of fathers and fathering on child psychopathology may be one path through which we can achieve a greater understanding of child mental health.

What impact do fathers have on the mental wellness or mental illness of their children?

The role of fathers’ parenting in child psychopathology

The first area of research that the authors review is the association between fathers’ parenting and children’s psychopathology. The reviewed studies examined fathers’ parenting through questionnaires and video-observations. According to the research reviewed, including a systematic review of 22,300 children in 24 studies:

- Greater parental involvement was associated with fewer behavioural problems in children

- Less involvement was associated with more behavioural and emotional problems, although these findings were more robust when parenting was assessed through video observations rather than questionnaires

- Children of parents who behaved disengaged and remote during observed interactions were also more likely to experience behaviour problems

- Likewise, children who reported low attachment to their fathers were more likely to be aggressive.

The role of fathers’ own mental health problems in child psychopathology

The second area of research reviewed is on fathers’ own psychopathology. The authors reviewed research showing that:

- Fathers’ depression is associated with a greater risk of behaviour and emotional problems among their children. One study suggested that this may be more so the case for sons than daughters.

The reviewed research also proposes pathways through which fathers’ depression affects their children’s psychopathology, including through:

- Impairment of fathers’ parenting and the parent-child relationship

- Strain on the relationship between father and mother

- The negative impact that a fathers’ depression may have on the mother.

Increased father involvement and more engaged styles of father-infant interactions are associated with more positive outcomes for children.

Conclusions

The authors concluded:

Fathers can fill a unique and distinctive role in their children’s lives and factors that impact upon the quality and amount of involvement fathers have with their children can affect children’s long-term development.

They also call for innovative approaches to engage fathers in parenting, and emphasise the need for more research into the benefits (and potential costs) of doing so through interventions.

Limitations

This review provides a great, brief overview of the state-of-the-science in fathers’ parenting research. There do appear to be two main limitations, not in the review, but in the parenting research reviewed in this paper. The first is that very little of the reviewed research appeared to take into account that (fathers’) parenting is not a one-way street. Parenting may influence child behaviour, but children’s behaviour also influences their parenting. For example, parents of children who display aggressive behaviour may be less keen to spend time with their children, because aggressive behaviour makes interactions more difficult. Children’s behaviour and characteristics may also influence the perception they have about their parenting. For example, children who are very anxious or depressed may perceive and report their parent as more rejecting. This is a problem if a study solely relies on children’s reports about their parenting.

In addition, and the authors of the review emphasise this as well, one problem that plagues research on parenting (whether mothers’ or fathers’) is the difficulty establishing causality, i.e. to determine whether it is really the parenting that causes children’s behaviour. For example, it is possible that Dads who opt to spend more time with their kids are not representative of all fathers; they may be better educated or in more supportive, positive relationships with the mothers of their children. These factors also influence child outcomes, so that the association between fathers’ parenting and child adjustment may be due to them, rather than being explained by fathers’ behaviour.

Similarly, parents do not only create an environment for their children, but they also pass on genes to their kids. Genetics are known to influence parenting and children’s psychopathology, so it is possible that the same genes that influence fathers to parent more sensitively and engaged also predispose their children to experience less psychopathology.

Luckily, there are research strategies that can rule out these alternative explanations, and it will be exciting to see more of these studies as the field of father-research continues to grow.

Our challenge now is to engage both parents (male or female) in effective interventions that optimise their children’s health and development.

Links

Primary paper

Barker B, Iles JE, Ramchandani PG. (2017) Fathers, fathering and child psychopathology. Current Opinion in Psychology, Volume 15, June 2017, Pages 87-92, ISSN 2352-250X http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.015.

Other references

Dotti Sani GM, Treas, J. (2016) Educational gradients in parents’ child‐care time across countries, 1965–2012. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1083-1096. [Abstract]

Photo credits

- Ben Francis CC BY 2.0

- By Ldorfman (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

- Rachel Kramer CC BY 2.0