The process of growing starts from birth and continues throughout life. Growing old is not something that can be stopped, but of course we can all modify our lifestyles in order to ensure a healthy transition through life. People have direct control over many aspects of healthy ageing (e.g. smoking, drinking, exercising, eating healthily, keeping mentally fit), and it is their own responsibility to act upon these aspects.

Most people start having concerns about their memory and cognitive abilities in midlife and older adulthood, mainly because this is the time when they encounter difficulties in these two areas. One can find a lot of advice about what do to in these specific situations but the question is what really works for maintaining and improving cognitive abilities in midlife and older adulthood?

We know that cognitive abilities change across lifetime and in many cases they show a decline during midlife and older adulthood, sometimes reaching the most severe form of cognitive deterioration known as major cognitive impairment as people reach their old age.

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate evidence on common modifiable risk factors for cognitive ageing that are largely under the individual’s personal control and can be implemented in midlife or later. The authors did not focus on factors linked to reducing the risk of dementia, although there are some shared risk factors between cognitive ageing and dementia.

This review covered a range of things that many of us can change in our later lives, such as diet and exercise like Tai Chi.

Methods

Database search

They searched the PubMed database up until May 2015 and took into consideration any eligible trial in any language as long as an English-language abstract was available. For identifying other clinical trials, they also examined reference lists from acquired trials and recent meta-analyses.

Inclusion criteria

Clinical trials participants were in their midlife or older. Midlife for women was considered around age 51 with the beginning of menopausal transition and 50 for men due to the fact that reductions in gonadal testosterone occurs gradually throughout adult life. Older adulthood is considered from age 65 for both men and women. They used only findings from clinical trials, which had at least 6 months between intervention initiation and outcome assessment.

Exclusion criteria

Excluded studies were those with participants who had any specific medical disorder, dementia or mild cognitive impairment. They only allowed at-risk populations, for example with elevated serum concentrations of homocysteine, but without end-organ disease, for example stroke.

Study characteristics

Studies were split into two groups. The authors identified 12 individually modifiable factors.

For ten of them they conducted a systematic review and quantitative synthesis:

- B-vitamins

- Dehydroepiandrosterone

- Ginkgo biloba

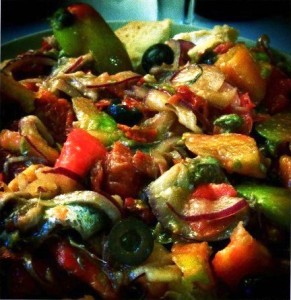

- Mediterranean diet

- Menopausal hormone therapy

- Mindfulness (including Tai Chi and Hatha Yoga)

- Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

- Social engagement

- Soy isoflavones

- Vitamin D

For the other two they relied on a recently published meta-analysis:

- Cognitive activity/cognitive training

- Aerobic physical activity

Results

Out of the 1,038 publications identified, 24 were found eligible and had 490 treatment arms for three groups of cognitive endpoints (memory, general intelligence and screening cognition).

The results of fixed-effects model for memory, general intelligence and screening cognition had no indication of heterogeneity among studies (Cochran Q: p=0.21 to 0.91, I2= 0.0 to 8.4%,), with similar results for global cognition (Cochran Q: p=0.31, I2= 4%). Similar findings for memory, general intelligence and screening cognition justified a general pooling if the network (Kendall rank correlation coefficient = 0.91) good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.89); with 73% of the variance being explained by the first principal component in a principal components analysis.

Global cognition

The analyses show that many of the interventions had no significant effect on any cognitive outcomes. Two had significant positive effects on global cognition, but they were small (Mediterranean diet + olive oil: standardised mean difference 0.22, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.27) or very small (Tai Chi exercise: standardised mean difference 0.18, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.29).

Memory

Two other interventions had small (Mediterranean diet + olive oil: standardised mean difference 0.22, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.32) or very small (soy isoflavone supplements: standardised mean difference 0.11, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.17) positive effects on memory.

The reviewers suggested that a Mediterranean diet supplemented by olive oil and Tai Chi may improve global cognition.

Conclusions

Out of the 12 considered individually modifiable factors, the results show that only a few of them show clinically meaningful effects that might improve cognitive ageing and even those effects are really small.

The Mediterranean diet was supported by just one clinical trial as having effects on cognitive efficacy and Tai Chi exercise showed that it might be an intervention that may benefit cognitive ageing, but only in two clinical trials. The authors classified Thai chi as a mindfulness intervention. There were also some positive results for memory but not global cognition of soy isoflavone supplements, but these trials included only women.

Limitations

- The authors did not define how they selected the 12 modifiable factors and why the decision to include or exclude others was made. The results show that there are differences between the factors, and although none have large or even medium effects those differences are not explored in the article.

- They focused only on single interventions, without offering any explanation why they did this or how this option strengthened their results. The number of included trials is very small considering so many factors were included and the authors did not conduct a power analysis to see how many trials would have been needed to show an effect.

- They only searched the PubMed database, which provides access to a just 16.5% of all the medical research published globally (Fraser et al, 2010). It is therefore likely that their review failed to include a great deal of useful and relevant evidence.

- Some of the factors, like the Mediterranean diet and Tai Chi practice can be highly different across cultures and practice. In the case of Tai Chi, the authors compared different mindfulness practices (defined as such by them) which can be very different (e.g. Hatha Yoga and Tai Chi).

- The separated two factors considered in the paper, cognitive activity/cognitive training and aerobic physical activity are just mentioned and the authors decided not to do a systematic review but to present results from another meta-analysis. It seems that these two have beneficial effects, but no data is presented in order to support this assumption.

Summary

Of course our individual choices about diet, exercise and social interaction have a huge impact on our mental and physical health throughout our lives. Some concerns only appear at the moment we encounter a difficulty and try to act upon it later rather than sooner. The results of this limited study point to the fact that there are modifiable factors that can be influenced by us all as individuals, but that is no great surprise.

No specific recommendations can be made based on this review, due to the absence of strong evidence for any of the individual modifiable factors that were studied. Future studies should throw the net wider to ensure that they are comprehensive and include all of the relevant evidence.

Literature searching for a truly systematic review requires a big net and lots of databases, not just PubMed.

Links

Primary paper

Lehert P, Villaseca P, Hogervorst E, Maki PM, Henderson VW. Individually modifiable risk factors to ameliorate cognitive aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Climacteric. 2015 Oct;18(5):678-89. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1078106. Epub 2015 Sep 11. [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Fraser Alan G, Dunstan Frank D. (2010) On the impossibility of being expert BMJ 2010; 341:c6815

What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/vex12zZBCi #MentalHealth https://t.co/GjSfI2iZsV

RT iVivekMisra What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/m3Dts6bDLi #MentalHealth https://t.co/q58pqflTjw

What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/FcEKbN13I7

What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/U7K9xQMZTf via @sharethis

What factors can ameliorate #cognitive #ageing? https://t.co/5cqjSktQnm #Evidence from a #Systematicreview

@Mental_Elf wondered if you could share this new @uniofbath ageing study with your contacts? Trying to recruit 65+s https://t.co/mwojKJLdUF

Can a Mediterranean diet supplemented by olive oil & Tai Chi improve global cognition? @raluca_lucacel on recent SR https://t.co/1QLAlu88v4

Don’t miss: What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/1QLAlu88v4

@Mental_Elf Not being able to understand that phrase!!

very interesting article #preventdementia @Mental_Elf https://t.co/Ly51voz0II

don’t miss – What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/8g6Bl2ygDP via sharethis

What factors can ameliorate cognitive ageing? https://t.co/jLzzRkb0jL