According to Bridge et al. (2019) the popular Netflix show “13 Reasons Why” was significantly associated with a 29% increase in suicide rates among young population aged 10-17 during April 2017. This study examined deaths by suicide during the release period of the show and post-release and the trends were higher. Ayers et al. (2017) suggested that the show may have elevated suicide awareness, but it also appears to have been associated with increased suicidal ideation. “There is social power and attendant social responsibility associated with the impact of media in the depiction of youth suicide.” (De Cates, Cole-King and Kutcher, 2017).

In this new review, Hawton et al. (2020) thoroughly examine the evidence related to adolescent cluster suicides including definitions, epidemiology, risk factors associated with them, mechanisms by which they occur, and effective ways to intervene and prevent them.

Suicide increases pointedly during adolescence, and young people (<25) are more likely to be involved in a suicide cluster, which is a major public health concern.

Methods

The researchers reviewed evidence in PsycINFO, Web of Knowledge, Medline, ASSIA, Sociological Abstracts, IBSS, and Social Services Abstracts up to December 2017 using multiple search terms. The selection criteria were: a) English language articles, b) papers identifying clustering of suicide or self-harm in 25 years old or younger. Expert knowledge in the area of research and an extended list of landmark papers on the topic were also included.

Results

Definitions and epidemiology

A suicide cluster is defined as the situation where more suicides than expected occur in relation to time, place (or both), and includes three or more deaths. It is very important to recognise at an early stage if individuals died by suicide were connected to each other in order to intervene and prevent further deaths. Adolescents (<25 years old) are more likely to be involved in a suicide cluster, which is a significant public health concern.

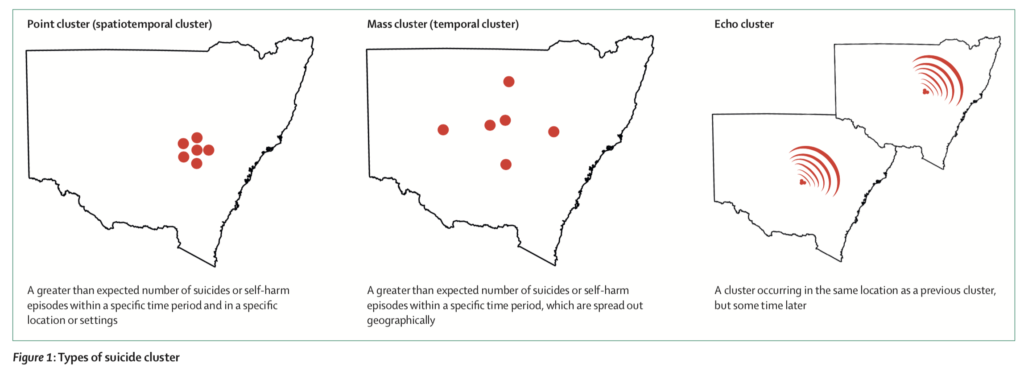

There are different types of clusters: point, mass and echo clusters (presented in the figure below):

- Point clusters occur in the same geographical location within the same time period.

- Mass clusters occur across different geographical locations but within the same time period. Increased online connections may be making mass clusters more prevalent.

- Less is known about echo clusters, which occur in the same geographical location as a previous cluster but sometime later.

Mechanisms

Four distinct mechanisms overlap to explain cluster suicide occurrence:

- Social Transmission: Otherwise defined as “suicide contagion”, exposure to death by suicide can increase suicidal ideation and behaviour in others. Exposure can occur directly, through knowing the deceased, or indirectly, through the media.

- Descriptive Norms: Perceptions around suicidal ideation and behaviour and how common it is among peers; thinking that suicide is more common among the community than it really is. Adolescents who believe suicidal behaviour to be widespread were indicated as more likely to consider suicidal behaviour themselves.

- Assortative Relating: Adolescents who are vulnerable to considering suicidal behaviour are more likely to be friends with one another. However, this would predict that adolescents closest to the deceased would be at the highest risk, yet research suggests that it is actually peers who are the least close who are at the highest risk. Therefore, the effects of assortative relating are relatively unknown.

- Social Integration and Regulation: The speed at which information is spread in close, tight-knit communities increases pressure to react to cultural expectations. This may create a tense environment for vulnerable teenagers, and therefore increase the risk of suicide.

Internet and social media influences

The rise of social media and the internet in general has led to increased concern regarding its influence, particularly on young people. Social networking may play a role in facilitating an increase in suicide. While it can help to memorialise the deceased and provide support, some students report that social networking hinders their recovery. This is due to seeing unexpected reminders of the deceased, or negative comments that interfere with their grieving process.

Since information can spread faster and further than ever before, the influence of suicide incidents can go beyond geographical boundaries. Young people within institutional settings may become aware of suicide before teachers and parents. This may affect a community’s efforts to respond to those affected and intervene properly. As a result, the prompt detection of a suicide cluster and its subsequent risks has become a challenge.

Nonetheless, the internet and social media have protective potential. They provide ways for young people to stay connected with others affected, promoting a sense of social connection and support. This may be useful for those who may not have access to face-to-face support in remote communities.

How we identify and respond to a suicide cluster

The aftermath of adolescent suicide is often significant and may cause community panic, while disorganised efforts to prevent suicides may be harmful. Careful advanced planning is important in trying to reduce a reactive response to a cluster suicide. Live monitoring of suicidal behaviour and interpreting any possible patterns enables early identification of potential clusters and prevention of suicide attempts. Concerns about potential clusters should then be reviewed by small response groups within communities.

Cluster Response Groups: Small groups of representatives from relevant organisations, such as schools and universities, with the ‘responsibility’ to ensure all information is captured. Individuals within organisations may also be better able to gauge the effects of a suicide and subsequent interventions, compared to an external organisation. A key responsibility of response groups is identifying people who are bereaved, affected, and vulnerable.

There are different types of suicide clusters: point, mass and echo clusters. (Figure 1 from Hawton et al, 2020)

Conclusions

This review suggests that suicide clusters are a phenomenon that happen more often in young people than in adults, while they tend to occur more in certain community and institutional settings, such as schools, universities, inpatient psychiatric units and young offender units.

Literature indicates various risk factors for cluster suicides including exposure to suicide, perceptions that suicidal behaviour is more common than it actually is, already considering suicide, and the speed at which information about a suicide can be shared. The use of internet and social media is important as technology has been found to have a negative impact in spreading information around suicide occurring among populations.

A special response group can reduce the chances of cluster suicides occurring by carefully planning a response in advance. For example, by supporting those who were closest to the individual (bereavement support), improving access to general mental health support across communities, and improving media coverage.

The use of internet and social media is important as technology has been found to have a negative impact in spreading information around suicide occurring among populations.

Strengths and limitations

The search strategy followed by Hawton et al. (2020) was comprehensive and extensive evidence was reviewed from a wide range of sources. The study was evaluated using The Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA). A score of 10 was calculated demonstrating the review was of high quality and included key aspects of a narrative review.

However, a meta-analysis pooling together the results of several studies would certainly improve objectivity. In order to fully understand this phenomenon, more scientific studies should be carried out, especially following a qualitative design interviewing people who have attempted suicide and their unique experience. Additionally, there is a profound need to replicate these studies in different cultural settings, as the majority of studies on cluster suicides have been conducted in Western cultures and mechanisms may differ cross-culturally.

We need to replicate studies in different cultural settings, as the majority of research on cluster suicides has been conducted in Western cultures and mechanisms may differ cross-culturally.

Implications for practice

The portrayal of suicide in the media must be done in a sensitive and ethical manner. Guidelines on language use should be enforced for news reporting and television programmes. Suicide prevention teams also need to be aware of the increased risk social media connections may bring about, and the influence it may have on an individual in response to a suicide. Lastly, further research is needed to identify those deeply affected by a suicide, but who do not clearly appear being at-risk.

Guidelines on language use, especially in news reporting and television programmes may help in preventing suicide clustering in the future.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Karima Abdou (@KarimaAbdou), Zainab Dedat (@Zainy24), Charlotte Steel and Laura Courtney (@lauraaacourtney) and the rest Bisby B Group: Anna Allis, Si Ang, Tanya Garg, Chloe Holgate, Freya Koutsoubelis and Imelda Minnock.

UCL MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a group of students on the Clinical Mental Health Sciences MSc at University College London. A full list of blogs by UCL MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Hawton, K., Hill, N., Gould, M., John, A., Lascelles, K., & Robinson, J. (2020). Clustering of suicides in children and adolescents. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 58-67. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(19)30335-9

Other references

Bridge, J. A., Greenhouse, J. B., Ruch, D., Stevens, J., Ackerman, J., Sheftall, A. H., Horowitz, L. M., Kelleher, K. J., & Campo, J. V. (in press). Association between the release of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Whyand suicide rates in the United States: An interrupted times series analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Leas EC, Dredze M, Allem JP (2017). Internet Searches for Suicide Following the Release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3333

De Cates, A., Cole-King, A. and Kutcher S. (2017). Suicide-related internet searches following the release of 13 Reasons Why. Mental Elf. Retrieved: 28 January 2020 from: https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/suicide/suicide-related-internet-searches-following-the-release-of-13-reasons-why/

Photo credits

- Photo by Federico Beccari on Unsplash

- Photo by Gonzalo Arnaiz on Unsplash

- Photo by Tim Bennett on Unsplash

- Photo by Steven Su on Unsplash

- Photo by Gaelle Marcel on Unsplash