Cannabis, the most widely used illicit drug in the UK, is on the decline amongst the adult population of England and Wales, but at the same time, and somewhat curiously, there are increasing numbers of people presenting to treatment services where cannabis dependence is stated as the primary concern. Similar patterns are apparent across Europe (EMCDDA, 2014).

Relatively little is known about the clinical interventions for cannabis. It is only recently, that clinical science has acknowledged that cannabis dependency actually exists. This is not a settled issue. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) makes no distinction between cannabis abuse and dependence, preferring to refer to a range of cannabis-related disorders. This poses an immediate problem for cannabis treatment and also the evidence-base for its efficacy.

It is extremely timely, therefore, that a significant step has been taken by Cooper and colleagues to address the knowledge deficit (Cooper et al, 2015).

The existence of cannabis dependency is still a hotly debated topic. Just check out the Mental Elf Twitter feed! :-)

Methods

Cooper and colleagues conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials assessing the clinical effectiveness of psychological and psychosocial interventions aimed at assisting regular cannabis users to reduce or cease their use.

Psychological interventions, broadly understood, are those that attempt to modify the behaviour of the individual. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and variants of Motivational Interviewing (MI) provide good examples.

Psychosocial interventions, meanwhile, are those that seek to adapt the behaviour not just of individuals, but significant others in their networks such as peers, friends and families.

The interventions assessed were for people aged 18 or above, delivered in an outpatient or community setting. Treatment delivered via a psychological treatment centre where participants were residing was included provided that cannabis treatment was not part of a broader package of interventions.

In total, 2 articles discussing 33 RCTs were included in the review. These studies were carried out in a range of countries, the bulk of which were the US (n=13) and Australia (n=7). Only English language trials were included.

Results

Where cannabis interventions are concerned the results are mixed and the picture is confusing. The authors looked at interventions in the ‘general’ population, which they contrast with those who had a diagnosed psychiatric condition. Often specific interventions are compared with other specific interventions so the efficacy of CBT is considered in comparison to Motivational Interviewing for instance. At other times specific interventions are compared with no intervention or with treatment as usual (TAU).

Where the ‘general population’ of cannabis treatment seekers are concerned:

- CBT tends work better in the long-run and is frequently seen to be more effective than offering no treatment at all

- It is unclear, however, as to whether it is more effective than just MI, but when combined with contingency management (the process of giving clients rewards such as vouchers to reinforce behaviour change), then CBT seems to be effective in the longer-term (12 to 15 months after the intervention has ceased to be delivered).

In the studies with people with psychiatric conditions, the results were more equivocal and limitations in the study designs of the original trials prevented more concrete conclusions from the review.

CBT courses and (to a lesser extent) 1-2 sessions of Motivational Interviewing improved outcomes in a self-selected population of cannabis users.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that more research is needed; a common refrain, but they do give a sense of where there are particular gaps in the evidence-base. Two main features are worthy of note.

Firstly, more research needs to be conducted on the efficacy of timings of interventions. It is often thought that the longer one spends in treatment, the more effective it will be. However, brief MI interventions, for instance, have been seen to be effective in certain conditions, so this is clearly something that warrants closer investigation.

Secondly, the routes into treatment need to be clarified. As it stands, it is unclear from a number of the trial studies how the participants were recruited because it was unclear whether they entered treatment voluntarily or not.

Future studies should consider the impact of recruitment methods and include inactive control groups and long-term follow-up.

Strengths and limitations

This is, however, a tremendously detailed and rigorous review. It benefits from the inclusion of a useful glossary and a plain English summary. It provides readers with the ‘state of the art’ of cannabis treatment. I use this phrase deliberately. Cannabis treatment in many ways represents an art or craft, much more than science. It is often unclear what kinds of provision there is for clients or their routes into treatment (Monaghan et al, 2016), but the review does a fine job of cutting a path through this jungle.

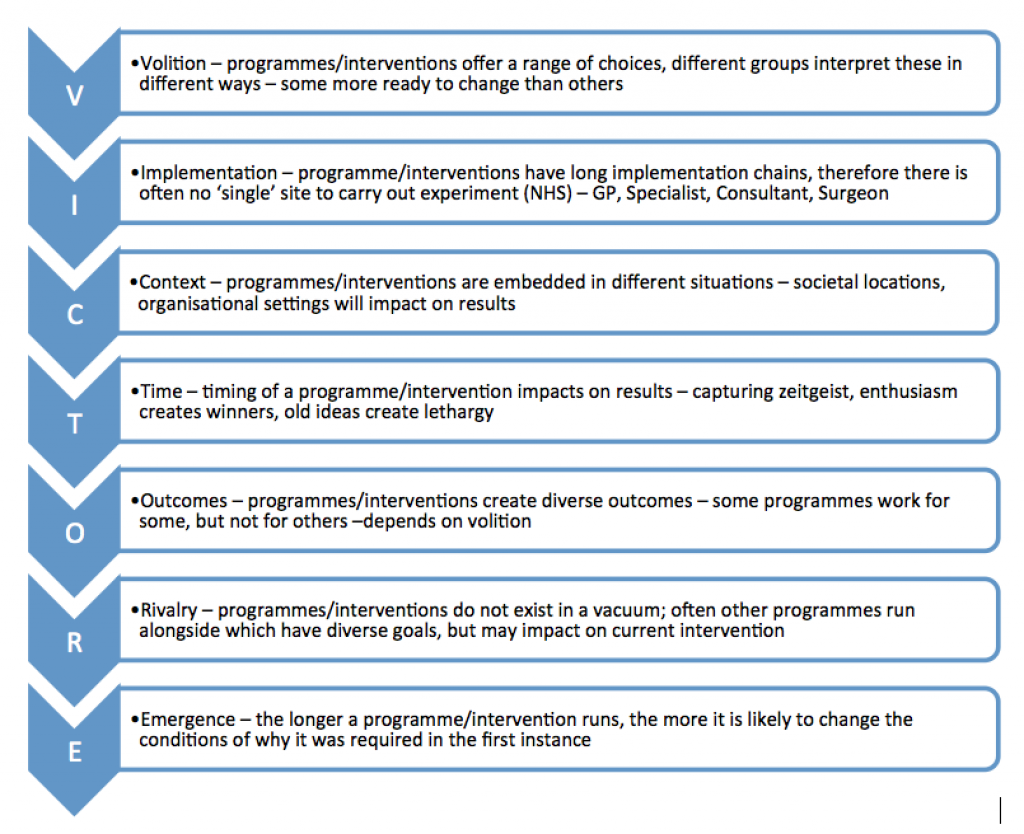

I am somewhat predisposed to be skeptical of the utility of RCTs to measure complex interventions. Space precludes a detailed account of the limitations here, but readers should turn to Pawson’s (2013) The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto for a thorough account of the drawbacks; reproduced here in diagram form.

Figure 1: Limitations of the RCT (Pawson, 2013)

There are 3 major issues worthy of note, which may impact on the findings. The first is that cannabis is a key part of the drug taking repertoires of many people, but not always in isolation (Parker et al, 1998). Polydrug use represents a challenge to RCT findings because the trialists cannot always be sure that those receiving the intervention are not receiving another intervention for other substances. The trialists cannot be sure because the clients may not be sure. Pawson refers to this as ‘rivalry’.

Secondly, in this review as most others there is a tendency to view cannabis as a heterogenous substance. This is misleading. A wealth of recent research on domestic cultivation (Decorte, et al, 2011; Potter) highlights how technological advances in both communications via the internet, but also horticultural equipment are producing new generations of cannabis connoisseurs who can tailor cultivation to personal taste. Furthermore, research on cannabis potency points to a variation in the kinds of cannabis available for consumers.

The final point relates to the inclusion of English language studies. Whilst this decision is perfectly understandable, it is, nonetheless, unfortunate. The recent EMCDDA (2014) report on cannabis treatment in Europe highlights how a number of cannabis-specific programmes are in existence in mainland Europe. Germany has four cannabis-specific programmes. These programmes use a range of modes of delivery including individual and group therapy as well as systems therapy and internet based counselling. Some are targeted at adolescents, but many also cater for adult substance users. It is possible that evaluations of these programmes would also yield valuable evidence.

Any systematic review that excludes non-English studies runs the risk of leaving out huge swathes of relevant evidence.

Summary

Declining frequent cannabis use in the UK and elsewhere exists alongside rising treatment presentations of cannabis dependence. However, relatively little is known about the efficacy of clinical interventions for cannabis treatment. Cooper and colleagues have taken significant steps to reduce this knowledge deficit. This is a welcome development, but there are still gaps in the evidence-base, which relate to the lack of clarity around cannabis consumption in light of significant changes to this market over recent years.

There remains considerable uncertainty about the kinds of cannabis now being consumed.

Links

Primary paper

Cooper K, Chatters R, Kaltenthaler E, Wong R. (2015) Psychological and psychosocial interventions for cannabis cessation in adults: a systematic review short report. Health Technol Assess 2015;19(56)

Other references

Decorte T, Potter G, Bouchard M. eds (2011) World Wide Weed: Global Trends in Cannabis Cultivation and its Control, London: Routledge

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2014) Treatment of Cannabis Related Disorders in Europe, available online at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/insights/2015/treatment-of-cannabis-related-disorders

Monaghan M, Hamilton I, Lloyd C, Paton K. (2016) Cannabis Matters? Treatment responses to increasing cannabis presentations in addiction services in England, Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 23 (1) 54-61

Parker H, Aldridge J, Measham F. (1998) Illegal Leisure: The Normalisation of Adolescent Recreational Drug Use, London: Routledge

Pawson R. (2013) The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto, London: Sage

Potter G. et al. (2015) Global Patterns of Domestic Cannabis Cultivation: Sample Characteristics and Patterns of Growing Across Eleven Countries, International Journal of Drug Policy, 26 (2) 226-237. [PubMed abstract]

Photo credits

- Neil. Moralee via Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND

- Jules Minus via DIYlovin / CC BY

- raym5 via Source / CC BY-NC-SA

- Rich Savage CC BY 2.0

- Pargon CC BY 2.0

- By nickolette from Bulgaria (the ganja cult) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons