The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted upon every facet of our lives, and the putative effects on population mental health and well-being have recently been highlighted (Holmes et al., 2020).

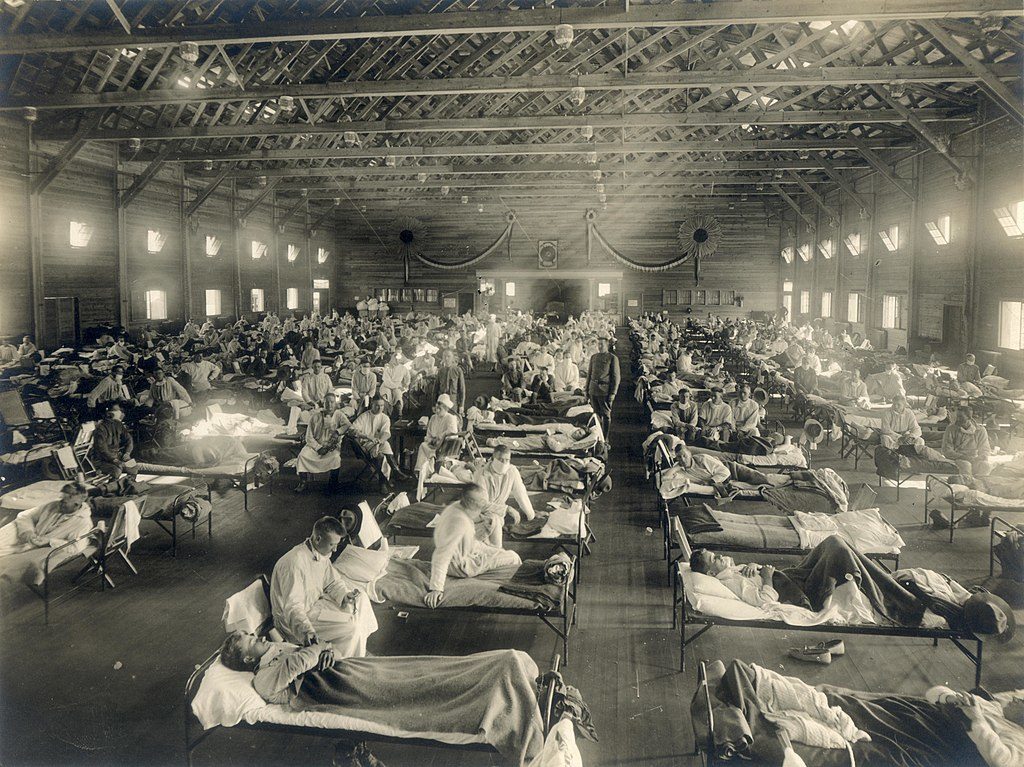

What some may not be aware of is that pandemics have long been associated with major mental illness, the best example being another respiratory infection; the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-9.

In this narrative review, written before the genesis of the COVID-19 pandemic, Kapinska et al (Kępińska et al., 2020) review the literature linking the 1918-9 pandemic to increased risk of schizophrenia. They go on to reiterate the possible effects of maternal influenza infection on subsequent development of schizophrenia in offspring (encompassing the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia), and discuss possible causal models between immune system dysfunction and schizophrenia.

Can the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-9 teach us something about the possible links between COVID-19 and severe mental illness?

Methods

This is a narrative review.

Results

Epidemiological data

The authors present the classic paper written by Karl Menninger in 1926, in which he outlined a case series of people who had experienced influenza, subsequently admitted to the Boston Psychopathic Hospital with acute psychoses. Of 80 people with full data available, 35 had an illness fulfilling criteria for a narrow definition of schizophrenia, “dementia praecox”, as opposed to delirium and other psychoses. Follow-up after 1-5 years indicated that two-thirds of these people had significant recovery, which would not have been the case in classical examples of dementia praecox (Menninger, 1926).

The authors then cover the “seasonality of birth” hypothesis of schizophrenia, where an excess incidence of schizophrenia was noted in children born in winter/spring, implicating a winter-borne virus in the aetiology of the illness. They cite work linking the 1957 influenza epidemic to increased incidence in offspring, using Finnish population data. The authors point out that these findings were not replicated in subsequent ecological studies. Given that identification of exposure to influenza is difficult to confirm, subsequent serological studies were conducted, a meta-analysis indicating increased risk of non-affective psychosis with childhood viral, as opposed to bacterial infections (Khandaker et al., 2012).

They also point out that this area is controversial, with discrepant findings amongst studies, for a variety of methodological and technical reasons. Furthermore, obstetric complications are more likely in those who have had influenza, and this is an independent risk factor for schizophrenia.

They postulate that influenza infection in utero could be a “hit”, i.e. a cumulative risk factor for later illness, linking this to the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia.

This narrative review suggests that influenza infection in utero could be a cumulative risk factor for later development of schizophrenia in the offspring.

Aetiological models

The review then focuses on relating the immune response to increased schizophrenia risk. This includes:

- Maternal immune activation (MIA), using animal models. Using these models, influenza infection in utero has been linked to changes in gene and protein expression, neurotransmitter levels and behavioural changes such as prepulse inhibition (PPI), which has been observed in schizophrenia. MIA is thought to possibly exert its effect through cytokines (signalling proteins which regulate biological functions, including innate and acquired immunity), produced by cells such as microglia. This is then linked to changes in brain development.

- Autoimmunity, where the immune system targets its own healthy cells and tissues. The authors use the example of autoimmune encephalitis, where antibodies are produced, the best example being NMDA receptor antibodies, which can produce psychotic symptoms. This model is suggested to have acute effects on the individual as well as maternal transmission. In essence, influenza is thought to provoke an autoimmune response, through mechanisms such as molecular mimicry.

This narrative review suggests that immune responses to influenza (e.g. maternal immune activation or autoimmunity) may increase the risk of the offspring developing schizophrenia.

Conclusions

Before drawing conclusions, the authors propose a number of new research questions brought up by their review. These include whether:

- There may be an association between influenza vaccination, seasonality of birth and risk of subsequent psychosis;

- MIA models are linked to an autoimmune response, if antiviral use in pregnancy is associated with decreased risk of psychosis;

- Studies of influenza vaccination in healthy volunteers may shed light on possible aetiological mechanisms.

They also consider the possibility of using pluripotent stem cells to examine the effects of influenza on induced pluripotent stem cell microglia.

They stress the importance of influenza vaccination, and suggest interventions for pregnant women who experience influenza infection that could be considered.

Finally, they make the point that understanding neuro-immune interactions has the potential to advance our understanding of the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia.

This review adds further weight to the importance of influenza vaccination, particularly in women who are pregnant or trying to conceive.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this paper is the serendipitous nature of its publication. When writing this to mark the centenary of the Spanish influenza pandemic the authors (like the rest of the world) could not have envisaged COVID-19 and its widespread effects.

The authors present a logical argument as to how one would examine a potential risk factor, in terms of putting together the epidemiological literature, and then discussing possible causal mechanisms. The section on the immune system and schizophrenia takes a very broad subject and makes an admirable effort to condense it into a few paragraphs.

The review is well-balanced; the authors present conflicting evidence for the epidemiological data, and leave it to the reader to make up their own mind. It is important to note that the literature here is difficult to make sense of, with a significant amount of heterogeneity amongst studies, and methodological limitations. It is worth noting that influenza did not come out as a strong risk factor for psychosis in a recent umbrella review (Radua et al., 2018), though this may have been due to the nature of studies included in the meta-analysis used for that review (Arias et al., 2012).

A limitation is the nature of the paper itself; a narrative review, as opposed to a systematic review. However, the nature of the topic and the disparate nature of a lot of the studies makes it difficult to see how a cogent systematic review could legitimately be written on this topic.

A valid case is made for causality, though this may have benefited from a structure, such as the Bradford-Hill criteria.

The section on the immune system, by having to cover such a wide topic, is at times difficult to follow for a non-specialist. Conversely, the comprehensive nature of this section could be viewed as a strength.

What is worth noting is the cautious nature of the review, which is to be welcomed.

When writing this review to mark the centenary of the Spanish influenza pandemic the authors (like the rest of the world) could not have envisaged COVID-19 and its widespread effects.

Implications for practice

The big question here, however, is not whether influenza infection has a causal relationship with the development of psychosis or schizophrenia in individuals or offspring. After all, influenza is relatively well-controlled, and effective vaccines are readily available.

The real question here is whether this may have relevance to the current COVID-19 pandemic. As with influenza, this could be thought of as direct effects on the individual, and possible effects on offspring.

Both influenza and COVID 19 are respiratory infections, though differ significantly in other ways. However, accumulating evidence does suggest COVID-19 involves the central nervous system (CNS), with retrospective data from Wuhan suggesting just over a third of patients had neurological symptoms, in addition to knowledge that other coronaviruses have effects on the nervous system (Mao et al, 2020).

The number of people infected by COVID 19 is potentially large, and therefore any small increase in risk could have larger effects at a population level. What will be vital is accurate assessment of psychiatric, and psychotic symptoms in people who have had mild and more severe forms of COVID 19, and use of techniques such as structural MRI or more novel imaging to ascertain possible markers of CNS involvement.

Another way of making sense of the relevance of influenza to the current pandemic is the suggestion that infection may be one of a number of “hits” along a causal pathway, and that it may confer increased risk, which may need to be mitigated against in the short and longer-term, to prevent development of psychotic illness.

It’s vital that we implement accurate assessment of psychiatric and psychotic symptoms in people who have had mild and severe forms of COVID-19.

Conflicts of interest

Sameer Jauhar (SJ) has received honorarium from Sunovian for educational talks, and King’s College London (KCL) has received renumeration for educational talks SJ has given for Lundbeck.

SJ has worked at the same institution as the authors (IoPPN, KCL), and published with one of the authors: Robin Murray.

SJ is funded by a JMAS SIM fellowship form the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

Links

Primary paper

Kępińska, A. P. et al. (2020) ‘Schizophrenia and Influenza at the Centenary of the 1918-1919 Spanish Influenza Pandemic: Mechanisms of Psychosis Risk’, Frontiers in Psychiatry. Frontiers, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00072.

Other references

Arias, I. et al. (2012) ‘Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis’, Schizophrenia Research, 136(1–3), pp. 128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026.

Holmes, E. A. et al. (2020) ‘Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science’, The Lancet Psychiatry. Elsevier, 0(0). doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1.

Khandaker, G. M. et al. (2012) ‘Childhood infection and adult schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of population-based studies’, Schizophrenia Research, 139(1), pp. 161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.023.

Menninger, K. A. (1926) ‘Influenza and schizophrenia’, American Journal of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Publishing, 82(4), pp. 469–529. doi: 10.1176/ajp.82.4.469.

Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China | Global Health | JAMA Neurology | JAMA Network (no date). Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/2764549 (Accessed: 20 April 2020).

Radua, J. et al. (2018) ‘What causes psychosis? An umbrella review of risk and protective factors’, World Psychiatry, 17(1), pp. 49–66. doi: 10.1002/wps.20490.

Photo credits

- Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine / Public domain