Stigma can be defined as a demonstration of power, through labelling, stereotyping, or discriminating against a group to establish their lower status (Link et al., 2004). Stigma towards individuals with mental health difficulties can have a range of harmful effects. One of these is to delay individuals from seeking the help they need (Corrigan, 2004; Rüsch & Thornicroft, 2014).

Previous evidence has found that public stigma, self-stigma and shame felt by sufferers contribute to compromised early recognition of symptoms, and avoidance of treatment in psychosis (Corrigan, 2004; Rüsch & Thornicroft, 2014). Psychotic disorders can have severe negative long-term outcomes, but sufferers have been shown to benefit greatly from early intervention, making this imperative (Tandon et al., 2010).

Evidence for the negative impact of stigma on access to care in psychosis is mounting, but this data has not yet been gathered together to provide an overall picture. In a newly published systematic review, Petra Gronholm and colleagues synthesise both quantitative and qualitative findings on the influence of stigma upon pathways to care for individuals who are either at risk of psychosis or actually experiencing their first episode (Gronholm et al., 2017).

Early intervention in psychosis is key, so it’s essential that barriers to help-seeking (such as stigma) are swept aside as quickly as possible.

Methods

The review protocol was pre-registered online to prevent changes after the fact. The authors followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement to ensure standards were met, and the quality of studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

The review separately considered qualitative (i.e. interview-based) and quantitative (i.e. numerical) data before merging them into a meta-synthesis. Quantitative data was summarised through a narrative synthesis, because statistical pooling of results was not possible with such a heterogenous set of studies.

The review identified and included 2 mixed methods research studies, 31 qualitative studies and 7 quantitative studies.

Results

- Most studies considered First Episode Psychosis (FEP) groups; some also recruited at-risk groups

- Qualitative studies were generally of good quality, while quantitative studies were mixed (e.g. unrepresentative samples, limited data)

- 33 qualitative studies (541 people included). These focused on 6 themes:

- Sense of difference

- Characterising difference negatively

- Negative reactions (anticipated and experienced)

- Strategies

- Lack of knowledge and understanding

- Service-related factors

- The principal findings of the quantitative research (692 people included) were:

- An increase in perceived stigma or stigma stress in at-risk groups at 1-year follow-up, which was associated with more negative help-seeking attitudes for psychotherapy and medication

- In FEP groups, service-stigma related to opposing psychiatric treatment, shame, and non-disclosure of symptoms. In relatives, worry that loved ones would be labelled ‘mad’ was a common reason for avoiding contact with services

- Young people felt ‘not normal’ following contact with health professionals

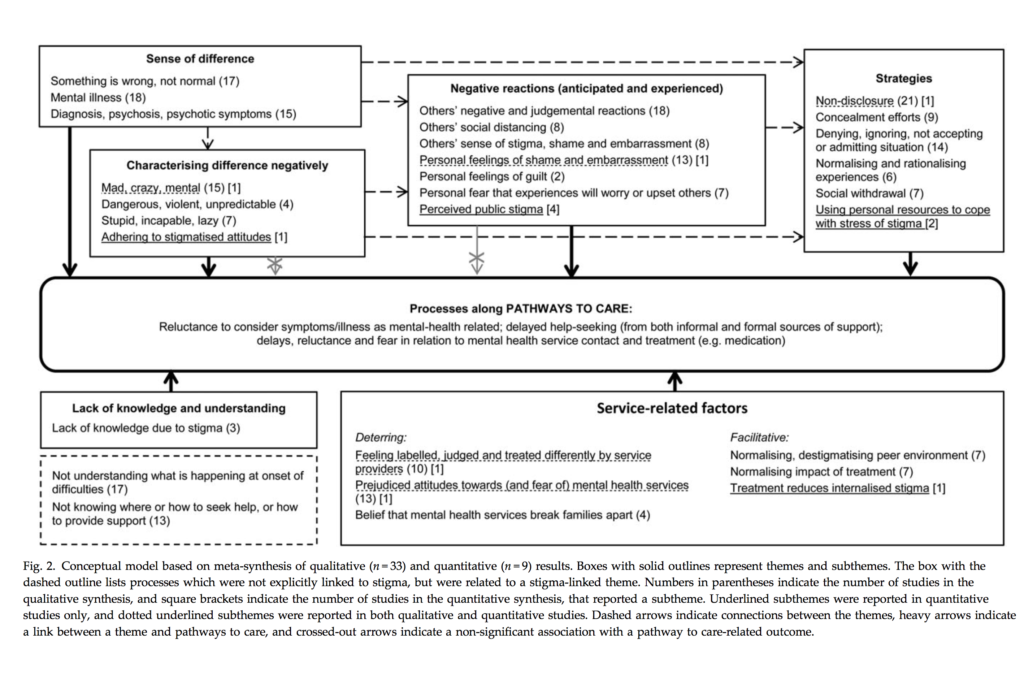

- The meta-synthesis led to a conceptual model of how the findings from qualitative and quantitative studies may fit together (see below).

The review found that stigma-related processes can influence help-seeking and service contact among first-episode psychosis and at-risk groups in many complex ways. Click the above figure to view in full size.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to investigate stigma in relation to pathways to care in the early stages of psychosis. The authors noted the interesting connections between findings. For example, feeling ‘different’ often led people to expect to be labelled and judged. This then related to denial or non-disclosure of difficulties, which could delay help-seeking. Consequently, efforts to increase awareness of mental health could seek to better understand the early signs, what they reflect, and how they can be supported.

Sadly, stigma was a constant in individuals’ help-seeking narratives, regardless of how much families knew about mental illness. Despite this, quantitative associations between stigma and pathways to care were often not statistically significant. What this contradiction means is unclear. The authors interpreted this as showing that quantitative approaches may struggle to capture the impact of stigma on help-seeking, as it is one of many complex variables. In this sense, qualitative approaches may be better at teasing out nuanced individual differences in experiences of stigma. Mixed-methods approaches (combining quantitative and qualitative) could help with this, but currently such evidence is lacking.

Conclusions

The authors summarise that:

The conceptual model derived from our findings can serve as a foundation for future research and efforts to mitigate the deterring influences of stigma on help-seeking and service contact.

Limitations

- The quantitative results were summarised in a narrative synthesis, so no statistical analyses were performed. Studies were too varied to be able to pool data statistically

- The studies were primarily from high-income Western countries, restricting the generalizability of the findings

- There were not enough studies looking at culture or ethnicity, which would enable subgroup comparisons

- The authors caution that findings should be interpreted within the context of wider structural/situational factors (e.g. service location, timing, availability) and financial reasons (e.g. cost of services, health insurance cover). There are also personal variables to consider, such as low perceived need for services, perceived ineffectiveness of services, or a preference to cope with a problem on their own.

Mixed methods research may be best suited to exploring how stigma can be minimised in people with first-episode psychosis or in those who are at-risk.

Links

Primary paper

Gronholm PC, Thornicroft G, Laurens KR, Evans-Lacko S. (2017) Mental health-related stigma and pathways to care for people at risk of psychotic disorders or experiencing first-episode psychosis: a systematic review (PDF). Psychol Med. 2017 Feb 15:1-13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000344. [Epub ahead of print]

Other references

Corrigan P. (2004) How stigma interferes with mental health care (PDF). Am Psychol. 2004 Oct;59(7):614-25.

Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY. (2004) Measuring mental illness stigma (PDF). Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):511-41.

Rüsch N, Thornicroft G. (2014) Does stigma impair prevention of mental disorders? Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:249-51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131961.

Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. (2010) Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 5. Treatment and prevention. Past, present, and future. Schizophr Res. 2010 Sep;122(1-3):1-23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.025. Epub 2010 Jul 23. [PubMed abstract]