Virtual Reality (VR) looks like something that will eventually develop into one of those weird growth pod-type things that Neo is hooked up to at the start of The Matrix.

The technology isn’t quite there yet (thankfully) – mostly because people can’t wear it for more than 15 minutes without feeling a little sick – but the software is definitely getting to the stage where a virtual world can be seamlessly given to our visual and auditory senses to create a new immersive environment.

It’s moved into the commercial scene relatively recently with entry level gear being available from quite a few companies – mostly in the gaming world – I wrote about this recently on my own blog.

This useful suspension of disbelief has meant that a number of practical and creative uses for it have started to be developed in the field of treatment and therapy. It’s been used in the realm of surgery in training for laparoscopic skills, and also operationalised to allow streaming of surgeries live from a 360-degree angle.

You probably recognise VR as something that looks like this, but with more arm flailing.

(Copyright TechRadar.net)

However, only in the last few years has this new technology been explored for use in the field of mental health.

Can virtual reality (‘In Virtuo’ exposure) provide a pragmatic and cost-effective solution to overcome distress, or will it pale to insignificance in comparison to ‘in vivo’ (‘real’ human) interaction?

Enter a new study published recently in the British Journal of Psychiatry by Bouchard and colleagues: Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a three-arm randomised controlled trial.

This three-arm randomised control trial aimed to help alleviate Social Anxiety Disorder; the typical treatment for which is gradual social exposure to overcome the fear of humiliation and judgement during social interaction.

Treatment is often conducted in a group setting, and therefore a number of practical challenges are often faced: therapy runs the risk of being less individualised, conducting group exposure therapy may be quite practically challenging for the therapist, and patients feel a lack of privacy during sessions.

The idea behind this study was to see if simulating social environments would be as effective as the standard therapy in vivo and thereby providing a pragmatic solution to the issue of privacy, while also enabling therapy to be contained in a single controlled space, as opposed to having to go to outside to different locations.

This novel study used virtual reality to expose people with social anxiety to virtual social situations to help them overcome their fears.

Methods

59 eligible participants recruited with Social Anxiety Disorder were randomly assigned to either VR exposure therapy, in vivo exposure, or placed on a waiting list.

All participants on the active arms (not on a waiting list) were given 14 weekly 60-minute sessions of CBT to accompany therapy as set out by Clark and Wells in 1995 (see other references); the only difference between therapies being that exposure sessions (weeks 7-14) were either conducted solely in VR or not.

In the VR condition, exposure time was mediated by the risk of ‘cybersickness’ experienced, and participants engaging in VR therapy were instructed not to engage in any exposure In Vivo.

All participants were given a series of nine clinical and experiential questionnaires to answer pre- and post-sessions, as well as followed up 6 months after therapy.

Measures included the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, and also the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire, and a couple of ‘presence’ questionnaires like this one that aims to define an individual sense of immersion in an environment.

Therapists also answered the Specific Work for Exposure Applied in Therapy (SWEAT) in an attempt to quantify the practical and financial benefit of each form of therapy.

Results

Results reported a highly significant drop in scores on all clinical measures between active arms and the waiting list.

The only significant difference between In Vivo + CBT and In Virtuo + CBT exposure was found on the Social Phobia Scale and the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; with In Virtuo exposure proving to be more effective.

After 6 months, no significant changes were found between post-treatment and follow up; the significant drop in scores were maintained. From follow-up scores, it was reported that In Virtuo therapy was only more effective compared to In Vivo when looking at the drop in scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale from pre-treatment to follow-up.

In addition to patient outcomes, therapists found In Virtuo significantly more practical and effortless as measured by the SWEAT.

None of the participants reported any significant sense of sickness through use of VR therapy. However, sessions may have varied in length depending of the ‘risk’ of cybersickness (between 20-30 minutes).

This small study suggests that virtual reality & CBT may be a viable alternative to exposure therapy & CBT for people with social anxiety disorder.

Conclusions

VR therapy doesn’t appear to be any better or worse than traditional CBT for social anxiety, but of course it may well more practical for patients and therapists. These results suggest that this form of therapy can be delivered in a controlled and simulated environment, and patients suffer virtually no loss of efficacy.

These results are more promising than an earlier randomised control trial for Social Anxiety Disorder that removed the cognitive component from each active arm to test the effect of the exposure alone. These results report that while compared to the waiting list, both VR and CBT therapy was effective, In Vivo was superior on most measures. This disparity in results is explained by Bouchard and colleagues to be due to the lack of the cognitive component in the trial that facilitates mental processing – essentially, being exposed to virtual characters only doesn’t cut it just yet.

Strengths and limitations

While these results look promising, the study doesn’t come without limitations. Namely:

- Lack of independent assessors to deliver the clinical and experiential measures

- Leaving out a comparison of group CBT

- Use of a relatively small sample – more than half of which had a university degree.

While reading the paper I wondered what the chances were of patients on the VR active arm giving self-administered ‘exposure therapy’ outside of sessions.

While participants were told not to engage in any ‘In Vivo’ exposure outside of VR training, it seems a little naïve to think that as confidence grows in the first 7 sessions through conversation with a therapist that patients aren’t going to venture into social situations outside of therapy to try their new found trust in themselves.

This might contaminate the efficacy of the VR treatment and mean that establishing a causal role in VR toward the reduction of symptoms of anxiety is harder, compared to just the existence of a safe and contained space, as symptoms may have dropped substantially before exposure.

Then again, ‘homework’ outside of sessions may not have been attempted if patients didn’t have the knowledge that they would be returning to the same contained space every week, and in that sense, VR therapy appears to provide that continued space as much as In Vivo exposure sessions.

If replication studies prove to build upon these results and try and look at the confounding factors outside of the sessions, e.g. the number of social situations encountered per week outside of therapy and a breakdown of symptoms reduction each week, the use of VR may be quite promising for use with individuals suffering social anxiety.

But how does virtual reality fare for other mental health difficulties?

Daniel Freeman and colleagues from Oxford University have also been using VR to treat persecutory delusions. A study conducted by his team was recently published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, and covered in a Mental Elf blog by Suzanne Dash: Virtual reality as a treatment for persecutory delusions.

Essentially, the authors concluded that VR provided a useful virtual world where individuals could encounter real-life situations, and that the skills learnt in this context could be transferred to the real world. Projects like Bravemind are also researching it’s use in PTSD.

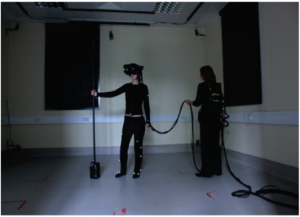

Daniel Freeman’s lab looks like this.

(Copyright Freeman et al., 2016)

Implications for practice

While VR has certainly made real leaps forward in the last few years, the current rigidity of its software, ‘cybersickness’ issues, and the ability for character interaction definitely has a way to go. The limitations of VR therapy alone are clearly illustrated in the Kampmann study (2016) mentioned earlier.

With the new developments in machine learning, artificial intelligence, and coupled with the rapid investment in the technology, I think we can expect VR to evolve into something much more complex and intuitive, and hopefully tackle the practical problems of cybersickness.

Given the connection made with a book, film, or computer game without being physically ‘immersed’ in the same way, it seems reasonable to think VR isn’t too far away, given the right narrative and design.

The next steps forward for research in this field of mental health rely heavily on the synthesis of technology, computing, neuroscience, and psychology, and more robustly establishing a link between VR exposure and lowering of symptoms.

Hopefully technology companies and academics can work together effectively to create a hybrid process to develop interventions to the benefit of patients.

André Tomlin caught up with Dan Freeman at the recent MindTech 2016 conference to talk about his lab’s use of VR:

Links

Primary paper

Bouchard S, Dumoulin S, Robillard G, Guitard T, Klinger E, Forget H, Loranger C, Roucaut FX. (2016) Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry Dec 2016, bjp.bp.116.184234; DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.184234 [Abstract]

Other references

Clark DM, Wells A. (1995) A cognitive model of social phobia. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment, 41(68).

Freeman D, Bradley J, Antley A. et al (2016) Virtual reality in the treatment of persecutory delusions: randomised controlled experimental study testing how to reduce delusional conviction (PDF). British Journal of Psychiatry 2016 1-6 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.176438.

Kampmann IL, Emmelkamp PM, Hartanto D, Brinkman WP, Zijlstra BJ, Morina N. (2016) Exposure to virtual social interactions in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour research and therapy, 77, 147-156. [PubMed abstract]

http://www.socialtech.org.uk/projects/bravemind/

[…] https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/anxiety/virtual-reality-for-social-anxiety-disorder… […]

just i want to give an observation, i think that vr can really heal all kind of fear and phobia, because those symptoms are developed by habit it’s an obsessed habit, it’s just a self negative image so VR can build fast a new positif self image that’s it, also we can develop all kind of new habits fast with VR reality.