Survivors of the Sousse terror attack in Tunisia retell the event as “absolutely manic” with people running for their lives (Callaway quoted in BBC, 2015, para.45). Thirty British tourists were killed in Sousse in 2015, only three months after two Brits were involved in the Tunisian Bardo museum attack (Stephen, 2015). The following year, British nationals were caught up in the barbaric attacks in Paris and Brussels.

Following these four overseas attacks, a screen-and-treat programme was implemented. The programme sought to identify, assess and treat victims when they came back to the UK.

After terror attacks, most victims do not seek help (Stuber et al, 2006), and 30-40% will develop a mental illness within 2 years (Whalley and Brewin, 2007). Could Screen-and-treat be the game changer that helps people who need help, get help?

Gobin and colleagues (2018) review the ‘screening’ component of the screen-and-treat programme.

In 2018, a memorial sculpture, named ‘Still Water’ was installed in Staffordshire to remember British victims of terrorist attacks abroad.

Methods

Victims of the four attacks, and their contacts (e.g. partner, first degree relative) were eligible for screening. Participants were accessed through the Metropolitan Police records, self-referral from online sources, and those who were contacted were advised to share the screening information packs with family and friends who were also affected.

Screening was a two-part process:

- Self-report questionnaire asking about personal history, alcohol use, smoking and symptoms of psychological disorders. If the questionnaire showed potential mental illness, they were screened as ‘positive’, and moved onto stage two.

- Clinical assessment was conducted by the Traumatic Events team at Maudsley Hospital or by local NHS teams. Recommendations were given for treatment.

Results

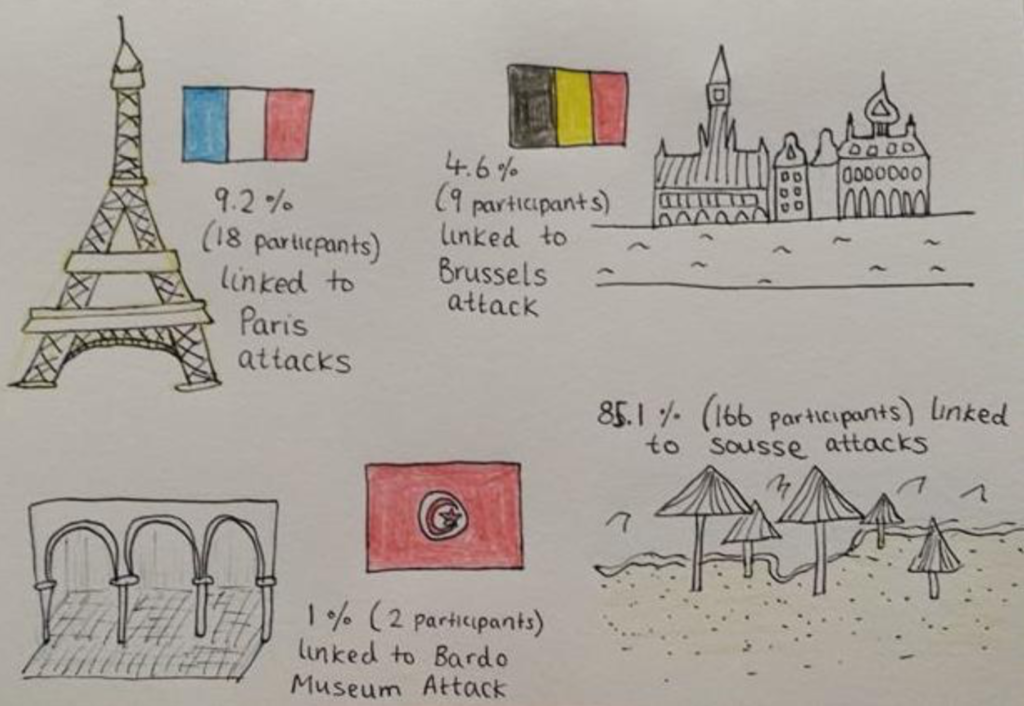

There were 195 respondents. Out of the 195 respondents, 167 were present at the attack and 28 were contacts. Eight participants were under the age of 17. The average age was 50 but ranged from 7 to 83 years. 61.7% of the respondents were female.

Stage 1 Questionnaire

- 179 adults screened positive (91.8%) to having potential mental health problems

- All 8 children screened positive

- More women scored positive than men, except in the alcohol use condition

- 72 adults and 3 children had not received any treatment prior to the screening

Stage 2 Clinical Assessment

179 adults and 8 children screened positive and were referred onto clinical assessment. However, the numbers decreased due to participants not being contactable (18), declining assessment (19), or no longer needing assessment (26).

- In total, 119 adults and 3 children were clinically assessed

- Of them, 78 were referred to treatment for a range of disorders

- 42: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and comorbid disorder

- 32: PTSD

- 4: Depression

- All 3 children assessed were referred to treatment for PTSD

The Traumatic Events team at Maudsley offered supervision and additional training to local NHS services to help provide trauma-focused interventions for individuals referred to treatment. 30% of local NHS services accepted further training and supervision.

The majority of participants in this research were associated with the Sousse attack in Tunisia, followed by the Paris attacks.

Conclusions

Gobin et al (2018) conclude that the screen-and-treat programme was a success. They suggest that without screening, many of the 78 individuals referred for treatment may not have sought help on their own accord. Gobin and colleagues (2018) recommended a few improvements for future screening programmes:

- Quicker implementation

- Data sharing between tourism companies and NHS trusts to improve access and services

- Wider advertisement to access more victims.

Strengths and limitations

This screening programme can be praised for opening its arms to those who wanted to be involved. Gobin and colleagues (2018) encouraged questionnaire sharing between family and friends and they put resources easily accessible online. As a result, they managed to recruit 51 participants outside of the Met Police records. This widened the scope of the screening programme gaining access to participants who may not have been contacted otherwise and subsequently may never have received treatment.

This research highlights the strengths of screening when 91.8% of the sample screened positive at stage one. However, approximately 21% did not attend clinical assessment either because they could not be contacted, or they declined the offer. This could perhaps be attributed to stigma. Screening has been used in the military in America, Australia and Canada post-deployment but it has been largely ineffective (Milliken et al., 2007; Rana et al., 2017), perhaps attributed to perceived stigma (Fertout et al, 2011). It might be fair to assume that stigma is more pervasive in the military, but this highlights why the impact of stigma must not be underestimated in any screening programme. Gobin and colleagues (2018) would not be able to eliminate stigma, however they could reduce its impact by directly addressing the issue in information provided or by increasing anonymity to elicit more honest answers (Fear et al, 2012).

Gobin et al (2018) sent screening packs in three waves, including additional reminders. This persistent approach may have caused further distress to victims if they did not want to be involved nor reminded of the event. For victims of disasters, secondary stressors can cause further harm to their mental health (Lock et al, 2012).

Rana et al (2017, p.1410) found that post-deployment screening was not effective at reducing the number of soldiers suffering from mental health problems. It also did not improve the likelihood that a soldier would seek help.

Implications: future research and recommendations for clinical practice

Outcomes from ‘screen-and-treat’ research studies in the UK have been encouraging (Brewin et al, 2008; Gobin et al, 2018). But, as the current evidence is exclusively small UK-based samples, more research is needed before taking the programme worldwide. Research needs to ask:

- Would screen-and-treat be effective post-natural disaster?

- How big of a population can we viably screen?

- If we undertake wide scale screening, do we have the required resources and skills to provide treatment?

This study found that only 16 out of 51 local NHS services agreed to have additional supervision and training provided by the Maudsley Traumatic Events team. We need to find out why so few services took up this offer and use any answers to inform future practice. There could be a standardised training programme for screen-and-treat to ensure consistency across NHS services. This would improve clinical practice.

Finally, more attention should be paid to anniversaries of traumatic events. Gobin et al (2018) conducted follow-up appointments where possible and found they were particularly helpful around the anniversary of the event. Anniversaries can cause an ‘anniversary reaction’ where people become distressed when reminded of the traumatic event (Myers, 1994). Future screen-and-treat programmes should look to use anniversaries as a time for outreach to actively engage with survivors. One year after the Manchester attack, memorial events helped survivors collectively commemorate, whilst directing people to help. This could be modelled for the future.

For the one-year anniversary of the Manchester bombing, there was a music concert and remembrance service to remember the victims of the attack.

Conflict of interest

Dr James Rubin (second author on this paper) is my lecturer at Kings College, London.

King’s MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a student on the Mental Health Studies MSc at King’s College London. A full list of blogs by King’s MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Gobin, M. Rubin, J. Albert, I. Beck, A. Danese, A. Greenberg, N. Grey, N. Smith, P & Oliver, I. (2018) Outcomes of Mental Health Screening for United Kingdom Nationals Affected by the 2015-2016 Terrorist Attacks in Tunisia, Paris, and Brussels (PDF). Journal of Traumatic Stress 31 pp.471-479

Other references

BBC. (2015) Tunisia Attack: Survivors’ story Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-33313022

Brewin, C. Scragg, P. Robertson, M. Thompson, M. Ardenne, P & Ehlers, A. (2008) Promoting Mental Health Following the London Bombings: A Screen and Treat Approach. Journal of Traumatic Stress 21 pp.3-8

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, Ministry of Defence & Ellwood, T. (2018) Dedication event for victims of overseas terrorism.

Fear, N. Seddon, R. Jones, N. Greenberg, N & Wessely, S. (2012) Does anonymity increase the reporting of mental health symptoms? BMC Public Health 12(797) pp.1-13 doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-797

Fertout, M. Jones, N. Greenberg, N. Mulligan, K. Knight, T & Wessely, S. (2011) A review of United Kingdom Armed Forces ’approaches to prevent post-deployment mental health problems. International Review of Psychiatry 23 pp.135–143

Lock, S. Rubin, J. Murray, V. Rogers, M B. Amlot, R & Williams, R. (2012) Secondary stressors and extreme events and disasters: a systematic review of primary research from 2010-2011. PLoS currents 4

Milliken, C. Auchterlonie, J & Hoge, M. (2007) Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Problems Among Active and Reserve Component Soldiers Returning From the Iraq War. JAMA 298(18) pp.2141-2148

Myers, D. (1994). Disaster Response and Recovery: A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals. Monterey California: Copy Editor

Rana, R. Burdett, H. Khondoker, M. Chesnokov, M. Green, K. Pernet, D. Jones, N. Greenberg, N. Wessely, S & Fear, N. (2017) Post-deployment screening for mental disorders and tailored advice about help-seeking in the UK military: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389 pp.1410-1423

Stephen, C. Shaheen, K & Tran, M. (2015) Tunis museum attack: 20 people killed after hostage drama at tourist site. The Guardian.

Stuber, J. Galea, S. Boscarino, J A & Schlesinger, M. (2006) Was there unmet mental health need after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41 pp.230–240. [Abstract]

Whalley, M & Brewin, C. (2007) Mental health following terrorist attacks. British Journal of Psychiatry 190 pp.94-96

Photo credits

- Photo by Jilbert Ebrahimi on Unsplash

- Angus Mills CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Benjamin Faust on Unsplash

- Ardfern [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons