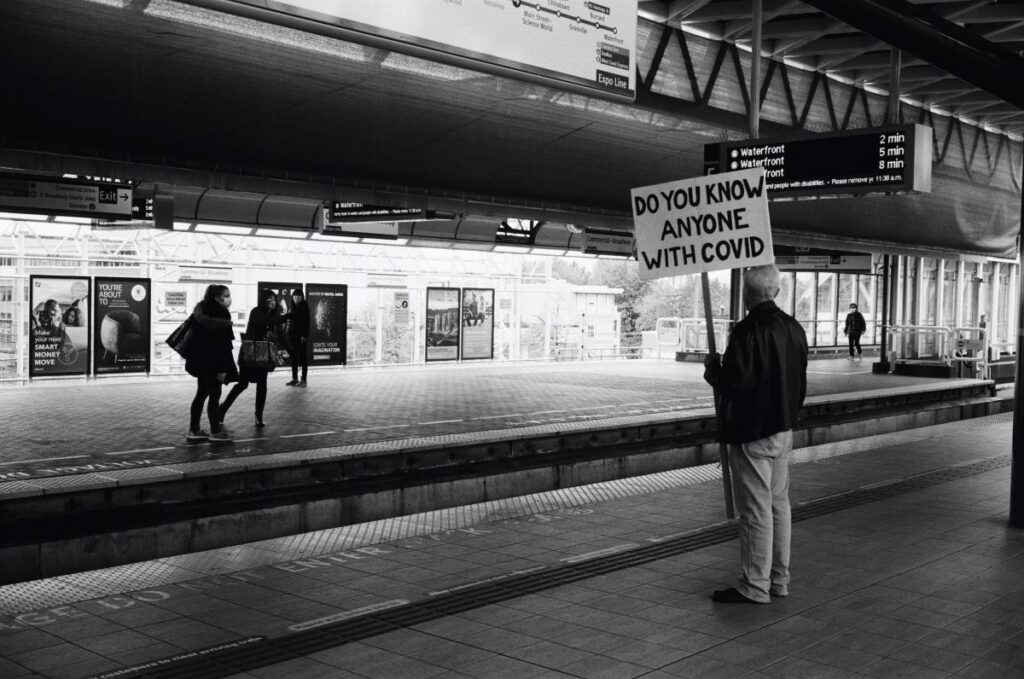

Vaccination offers the UK the best opportunity to control the COVID-19 pandemic (Majeed & Molokhia, 2020), but public scepticism and vaccine hesitancy poses a threat to this exit strategy.

The authors of a recently published study (Freeman et al, 2020) acknowledge this:

Vaccine hesitancy can have effects for both the individual (a greater risk of having the disease) and potentially the community (greater virus transmission).

Professor Daniel Freeman and his team at the University of Oxford aimed to estimate provisional willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, identify predictive socio-demographic factors, and determine potential causes. They described their primary focus to be explaining vaccine hesitancy at an individual psychological level.

“Beliefs, which are potentially amenable to change, are well-established drivers of actions.” Thus, by identifying a “broad cluster of cognitions that may inhibit or facilitate” vaccine uptake, they aimed to estimate the extent of the potential problem (delay or refusal), identify pockets of pronounced hesitancy (trends in the population), and determine the content driving factors for vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccination offers the UK the best opportunity to control the COVID-19 pandemic, but public scepticism and vaccine hesitancy poses a threat to this exit strategy.

Methods

A sample of 5,114 participating adults (over the age of 18) filled out an online survey (OCEANS II – Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey) between 24th September – 17th October, 2020. The non-randomised survey was done via a market research company. The quotas were based on UK Office for National Statistics population estimate data for gender, age, ethnicity, income, and region. Until the respondents had provisionally agreed to complete the survey, they did not know the topic in question.

As well as using already established measures, the authors devised a number of scales to be used in the survey:

- Oxford COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy scale (15 items; higher scores indicate a higher level of vaccine hesitancy)

- Oxford COVID-19 vaccine confidence and complacency scale (20 items; higher scores indicate a greater degree of negative attitudes)

- Oxford trust in doctors and developers questionnaire (16 items; higher scores indicated greater disrespect from doctors, and greater negative views of vaccine developers)

- Attitudes to doctors and medicine questionnaire (19 items; higher scores indicate greater positive attitudes to doctors or medicine)

- NHS experience questionnaire (8 items; higher scores indicate fewer positive NHS experiences and greater negative NHS experiences)

- OCEANS coronavirus conspiracy scale (7 items; higher scores indicate greater endorsement of coronavirus conspiracy beliefs)

- Following of UK government coronavirus guidance (participants were asked to rate how often they followed nine key aspects of government guidance; higher scores indicate greater adherence to guidance).

Results

Vaccine hesitancy

- 892 (76.1%) of participants did not show any clear vaccine hesitancy (a response rating of 4 or 5) on any of the seven items

- While 1,222 (23.9%) endorsed at least one of the items with a hesitant response

- 596 (11.7%) participants endorsed four or more of the seven items (i.e. over half) with a clear vaccine hesitancy response (a rating of 4 or 5). This group can be considered strongly vaccine hesitant

- 196 (3.8%) participants endorsed all seven items with a clear vaccine hesitancy response, and this can be considered a very extreme group.

Vaccine hesitancy and socio-demographic factors

- Nearly 72% were willing to be vaccinated

- Nearly 17% were very unsure about vaccination, and nearly 12% were strongly hesitant

- Vaccine hesitancy was associated with lower age, female gender, lower education, lower income, black and mixed ethnicities, not being single or widowed, not being a homeowner, not being employed full-time, not retired, a change in working, and having a child at school. The R 2 scores indicate that each variable explains only a small percentage of vaccine hesitancy, with age explaining the highest amount (3.8%)

- When all the socio-demographic variables were entered into a multiple regression (see online supplementary materials), the R 2 was 0.098. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was significantly lower in those at very high risk of a severe COVID-19 illness course compared with those at moderate risk or low risk, and those at moderate risk were significantly lower in hesitancy scores than those at low risk of a severe illness course

- Hesitancy was not associated with political views, but more right-wing political views were associated with coronavirus conspiracy beliefs

- Higher levels of vaccine hesitancy were associated with less following of all guidelines and less likelihood of taking a diagnostic or antibody test.

Explanatory factors

One explanation is offered by the beliefs model which incorporates beliefs about the collective importance, efficacy, side-effects, and speed of development of a COVID-19 vaccine. Beliefs about a COVID-19 vaccine are a major predictor of vaccine hesitancy and accounted for 86% of the variance in vaccine hesitancy.

A second model, the mistrust model, highlighted two higher-order explanatory factors, which were termed ‘excessive mistrust’ (and conspiracy theories) and ‘positive healthcare’ (negative views of doctors, and need for chaos, and ‘positive healthcare experiences’) respectively. The authors stated that:

In essence, willingness to take a vaccine is about trust: that the vaccine is needed, that it will work, and that it is safe. Therefore, unwillingness to take a vaccine will be more likely when excessive mistrust is an individual’s default position. If an individual is mistrustful of experts, authority, and institutions, the same tendency will apply to attitudes to a vaccination.

Nearly 72% of people surveyed were willing to be vaccinated, nearly 17% were very unsure, and nearly 12% were strongly hesitant.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is relatively evenly spread across the population. Willingness to take a vaccine is closely bound to recognition of the collective importance. Vaccine public information that highlights prosocial benefits may be especially effective. Factors such as conspiracy beliefs that foster mistrust and erode social cohesion will lower vaccine up-take.

Vaccine public information that highlights prosocial benefits may be especially effective.

Strengths and limitations

This study is an excellent addition to the literature as:

- It highlights key issues around vaccine hesitancy and identifies trends that allow an estimate of the extent of the potential problem

- The methodology was logical and uses a large sample size (5,114 participating adults)

- The survey used a mixture of existing scales which were adapted to the current situation, and new scales that were designed accordingly

- The study has the potential to inform future research and policy, particularly for science communication and public messaging.

However, the full extent to which expressed intent to take a vaccine is associated with actual behaviour remains unknown. There is scope for further research to increase confidence in findings and confirm the relationship between an individual’s behaviour and their beliefs.

A further limitation to the survey data is the non-probability online quota sampling method which was used, that will have introduced bias to who was approached to take part. As a whole, the respondents in this survey were broadly representative of the adult general population on a number of basic demographic features (although, for example, levels of higher education were slightly high) but it is unknown whether individual respondents were representative of the general population. Thus, prevalence estimates in particular must be treated with caution, alongside identification of demographic predictors. Finally, the use of non-validated measures may challenge the external validity of these findings.

“We do not know whether the beliefs, attitudes, and perceived experiences actually cause willingness to take a COVID-19 vaccine.”

Implications for practice

For the authors, the plan is to: “use detailed qualitative interviewing, guided by the results of the survey, to deepen our understanding of vaccine hesitancy, and then conduct experimental tests to assess change and causation.”

In the short term, the overall implications from this study include the importance of stressing vaccine benefits in public health messaging. The necessity for transparency on vaccine safety and efficacy have also been highlighted.

“Careful testing and refining of messaging across the spectrum of hesitancy will be needed. The survey findings also indicate that materials may benefit from highlighting the many positive contributions that NHS staff make. There is an urgent need to counter misinformation, ideally by ‘prebunking’ or inoculation, and provide strong presentation of accurate information. The findings also reiterate the longer-term work needed to rebuild trust in experts and institutions.”

There is an urgent need to counter misinformation about the coronavirus vaccine.

Statement of interests

None.

Want to know more? Sign-up for the #OxfordMentalHealth webinar on 28th April

The first author of this paper (Prof Daniel Freeman) will be in conversation with Channel 4 journalist Jon Snow at the next #OxfordMentalHealth webinar which takes place at 6-7pm BST on Wednesday 28th April. You can sign up for a free ticket here.

Links

Primary paper

Freeman, D., Loe, B. S., Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., Waite, F., Rosebrock, L., … & Lambe, S. (2020). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychological medicine, 1-15.

Other references

Majeed A, Molokhia M. Vaccinating the UK against covid-19. BMJ. 2020; 371 :m4654. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4654

Photo credits

- Photo by Daniel Schludi on Unsplash

- Photo by Aljoscha Laschgari on Unsplash

- Photo by Ariana Suárez on Unsplash

- Photo by Martin Sanchez on Unsplash

- Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash

- Photo by Moses Lee on Unsplash