Happy New Year to one and all from down here in the woodland.

To start us off with a bang for 2024, we have a blog from Lizzie Furber, one of our social care elf editorial team, highlighting a scoping review that is the first of its kind in the UK.

Introduction

LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bi, Trans, Queer, Questioning, and other minoritised sexualities and gender identities) young people are overrepresented in residential social care settings (Schaub et al. 2022a) but their voices are largely absent from research into young people’s care experiences (Schaub et al. 2023). More broadly, social work practice with LGBTQ+ communities is an under-explored area with research finding that social work education does not prepare students for work with LGBTQ+ people (Inch, 2017) and that social care staff lack the relevant skills and training (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2020, Steels & Simpson, 2017).

In Residential Social Care Experiences of LGBTQ+ Young People in England Schaub, Stander and Montgomery build on a systematic scoping review (Schaub et al. 2022a) to address the significant knowledge gap relating to the voices and experiences of LGBTQ+ young people. This is the first study of its kind in England. The research shines a light on the institutional discrimination faced by LGBTQ+ young people in the care system, taking an intersectional and co-produced approach. Health inequalities are explored, with recommendations for improving the experiences of LGBTQ+ young people and including their voices in service design and delivery.

Research in young people’s residential settings highlight that many experience discrimination due to gender identity and sexuality.

Methods

The authors used their previous scoping review to develop the research questions:

- What are the experiences of LGBTQ+ young people in residential care?

- Do LGBTQ+ young people in residential care have particular needs and, if so, what are those?

The research used an intersectional minority stress framework to explore the residential care experiences of LGBTQ+ young people in the context of their multiple and intersecting identities. Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 2003) considers the impact of stigma and discrimination (experienced, anticipated, and internalised) and how chronic exposure to these stressors has a cumulative effect and can result in poor mental and physical health outcomes. Intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1989) looks at how different minoritised identities and forms of inequality intersect, exacerbating the oppression and discrimination experienced.

Co-production techniques were used in research design, data analysis and recommendations. Co-production took place with a group of LGBTQ+ young people with lived experience of social care and with other stakeholders.

20 LGBTQ+ young people (aged 16-24) who had lived in residential care settings for longer than three months were interviewed via Zoom. The interview covered care experiences, needs and relationships. Participants were able to have a supporter present during the interview and were able to check transcripts for discrepancies before analysis.

Data was analysed using a reflexive thematic analysis procedure (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021) to identify patterns across the dataset.

Results

Analysis of the interviews identified four themes:

- Widespread discrimination and marginalisation

Participants widely reported experiencing stressors relating their LGBTQ+ identity/identities while in residential care and did not feel protected from discrimination. Participants with multiple minority identities reported higher levels of discrimination. Many participants reported rejection due to LGBTQ+ identities or non-affirming environments as a main reason for coming into care. Most participants had experienced placement instability and reported lack of LGBTQ+ affirming support as contributing to this.

Bullying and harassment were common experiences both in residential care and in school, particularly when moving to new areas. Participants also experienced harmful attitudes and behaviour from social work and social care staff. Some of the young people described experiences where their LGBTQ+ identities were characterised as, “Pathological, predatory or circumstantial and due to trauma experienced before entering care.” (Schaub et al., 2023:8).

Some young people were told not to discuss their gender identity or sexual orientation with other residents as a way of managing risk. Trans and gender diverse young people reported gender policing, such as being prevented by a support worker from buying clothes that were too “masculine”. These issues were compounded for the young people who also needed support to explore racial identities and the intersection between race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

- Unmet mental and sexual health needs

Almost all of the young people interviewed described experiencing mental health problems while in residential care. The most common forms of mental distress were anxiety, depression, suicidality, and self-harm. Many participants connected these difficulties with traumatic experiences both before and while in care. Some participants reported positive experiences of counselling and therapeutic care, however most reported poor experiences with mental health services, particularly CAMHS.

In terms of access to sexual health services and information, “there was evidence of significant and concerning healthcare gaps” (Schaub et al., 2023:10). LGBTQ+ inclusive sexual health and relationships education was lacking. The education that was provided focused on heterosexual relationships between cisgender people, which leaves LGBTQ+ young people without the information necessary to make informed sex and relationship decisions. Schaub and colleagues flag this as a particular concern with neurodivergent young people who can be at higher risk of sexual exploitation. One autistic participant described seeking support from his social worker after being raped and not being provided with support or information about the risk of sexually transmitted infections and blood borne viruses.

- Importance of affirming professional relationships

A minority of the young people interviewed described positive relationships with professionals involved in their care. What the young people valued in the professionals supporting them was affirmation and celebration of their LGBTQ+ and other identities and supporting their rights as LGBTQ+ people. Positive examples of this affirmation and support included professionals challenging bullying, not presuming heterosexuality, using inclusive gender language, giving space for young people to explore their identities, and providing them with LGBTQ+ resources. Trans young people found support to access gender identity clinics of key importance. All of the young people who had supportive relationships with professionals cited them as central in their development of a positive LGBTQ+ identity.

- Resilience and self-relying strategies

Despite the adversity they had faced, participants demonstrated high levels of resilience and resourcefulness. The young people were able to describe coping mechanisms and informal support networks of friends, LGBTQ+ groups and family. Most participants described the most helpful support as being outside of care and formal support networks such as social workers, schools and CAMHS. Participants had developed high levels of skill in navigating education, health and care systems that were not responsive to their specific needs, and impressive self-advocacy.

LGBTQ+ young people widely reported un-affirming care and experiences of prejudice and discrimination.

Conclusions

“[O]ur findings demonstrate widespread interpersonal and institutional discrimination and prejudice; placement instability and sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression-related family and caregiver rejection. These challenges were particularly acute for those with multiple intersecting marginalised identities and trans and gender diverse young people, who experienced pervasive gender policing and regulation.” (Schaub et al., 2023:13).

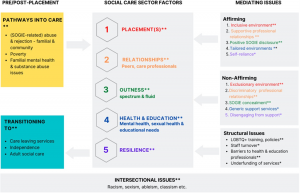

The conclusions of the paper build on the international evidence that affirming residential care experiences are crucial in order to promote the wellbeing of LGBTQ+ young people. The authors use the findings from this paper and their systematic scoping review to develop a model for understanding the key factors in shaping LGBTQ+ young people’s positive or negative experiences and wellbeing.

Figure 1 Conceptual model for understanding (un)supportive residential social care environments for LGBTQ+ young people. *, Findings from residential care qualitative study. **, Findings from both residential care study and international scoping review of the research evidence.

Source: Primary Article.

LGBTQ+ young people widely reported un-affirming care and experiences of prejudice and discrimination

Based on the findings the authors provide policy practice and research recommendations to improve the experiences of LGBTQ+ young people in care:

- Local authorities and residential homes to adopt targeted policies for supporting LGBTQ+ young people.

- Mandatory LGBTQ+ knowledge training for all residential staff and social workers, combined with coaching or reflective supervision.

- Assess care professionals and foster carer attitudes and competence in supporting LGBTQ+ young people to reduce risk of placement breakdown.

- Further research is necessary given the large gaps in knowledge in this area in the UK, including longitudinal research with LGBTQ+ young people.

- Young people should be involved in the development of services, practices and policies.

Strengths and limitations

The methodology used is a considerable strength and guards against the homogenisation of LGBTQ+ identities common in LGBTQ+ health inequality research (McDermott et al., 2021). An intersectional approach enables understanding of the “interdependent inequalities and power imbalances” faced by young people with multiple minoritised identities and allows the needs of LGBTQ+ young people to be considered holistically.

Use of the Minority Stress Model promotes a non-pathologising understanding of the increased sexual, physical and mental health risks for young LGBTQ+ people, framing these health inequalities within the context of ongoing discrimination, oppression and inappropriate service responses. This is of particular importance given that pathologising approaches were reported by participants as a common, harmful experience with professionals.

The voice of LGBTQ+ young people is elevated, both through the co-production of the research with residential care experienced LGBTQ+ young people, and also through the diversity of the sample in terms of gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, neurodiversity, physical disability and location across England. Use of direct quotation throughout the paper brings nuance that is difficult to find in studies that don’t use an intersectional approach. For example, discussion of how religion can be both a source of discrimination and a source of strength and the need for LGBTQ+ young people of faith to navigate their experiences of community and religion.

This is a rich study, but with a sample group of 20, limited to England, it isn’t generalisable. It would be interesting to repeat the study in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to find out if different legislative and policy contexts lead to difference in experience.

The sample was self-selecting, responding to calls for participants. The study therefore doesn’t capture the voices of young people who are not “out” or who do not feel safe to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity in their current placement. Online interviews enabled LGBTQ+ people to participate from across the England and increased accessibility in many regards, but also excluded participants who are unable to access the internet or do not have a private space in their accommodation.

Schaub and colleagues note participant emphasis on self-managing their care journey as a surprising finding. The authors recognise the impact of trauma on mental and physical wellbeing through application of the Minority Stress Model. The core principles of Trauma-Informed Care state the importance of choice and control over healthcare decisions, alongside use of people’s strengths and collaborative working to empower them (Menschner and Maul, 2016). In this context, perhaps the importance for participants of self-managing care and being in control of their care journey is less surprising and should form the basis for recommendations on how to support LGBTQ+ young people to navigate health and social care systems.

The authors state that the findings are in line with anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive social work that, “involves not only tackling or reducing immediate discrimination (anti-discriminatory practice) but also challenging structural and systemic discrimination (anti-oppressive practice),” (Schaub et al., 2023:14). However, the recommendations focus mainly on inter- and intra-personal dimensions such as local guidance, assessment of frontline staff, training and reflective supervision for individuals. Wider structural issues could have been considered, not least because the support for LGBTQ+ specific sexual health and relationship education is currently directly contradicted by the Government’s plan for a review of sex and relationship education (DfE, 2023).

As the first study of its kind in the UK, this paper provides important insight into the experiences of LGBTQ+ young people in the care system. It is a strong foundation for further exploration of the discrimination and oppression faced by LGBTQ+ young people in residential care settings and how social workers can deconstruct the barriers to safe and supportive care.

Implications for practice

As referenced, research has consistently shown that social workers do not feel prepared for working with LGBTQ+ people. This study presents findings that develop key knowledge and understanding about the needs and experiences of LGBTQ+ young people. This is relevant to all in social care, not just those who work with children and young people. Schaub and colleagues explore how experiences of trauma and discrimination can have long-term impacts on health and wellbeing and state that LGBTQ+ young people in residential care are at heightened risk of “ageing out” of care and experiencing homelessness and social deprivation.

Anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive practice is central to social work. This research sets out widespread injustice faced by young people as a result of sexual orientation and/or gender diversity. It was interesting to note that the authors describe how other young people’s services such as homelessness and youth work programmes have made substantial progress in implementing targeted policies and practical recommendations for supporting LGBTQ+ young people but similar policies and guidance do not exist in English Local Authorities.

Earlier research has considered the problem of heteronormativity in social work practice (Cocker and Hafford-Letchfield, 2010). The potential reasons why social work is lagging behind other sectors in promotion of LGBTQ+ rights is something for us, as a profession committed to social justice, to reflect on. This is of particular importance given the current climate of Government resistance towards young people receiving affirming support in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity, evidenced most recently by the conversion ‘therapy’ ban being dropped from the King’s Speech.

What’s clear is that relationship-based practice, professional curiosity and advocacy are of pivotal importance to LGBTQ+ young people, all of which are skills that are already in the social work toolbox and ready to be developed in work with resourceful and diverse young people like the participants in the study.

Statement of interests

No conflict of interest.

Links

Primary paper

Other references

Improving Social Care with LGBTQ+ Young People – watch the authors discuss their research as part of Social Work England’s World Social Work Week programme.

Photo Credits

- Photo by Igor Omilaev on Unsplash

- Photo by Jordan McDonald on Unsplash

- Photo by Andra C Taylor Jr on Unsplash

- Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash

-

Photo by daniel james on Unsplash