In this blog, I preferred the use of the term inequities to inequalities, which is consistent with the existing literature.

This four-part Lancet Series explores the impact of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination on health. The authors, Devakumar et al. (2022), bring these issues into sharp focus, and examine how division, from a systems level right down to that between individuals, has influenced health outcomes unfavourably throughout history.

This series is informed by other series commissioned by The Lancet, such as Culture (Napier et al, 2014) and Migration (Abubakar et al, 2018). Indeed, this piece further progresses the conversation from a previous blog on race, ethnicity, and disparities in mental health experiences and outcomes written by Kam Bhui.

No longer can we ignore racism, xenophobia and discrimination as important social determinants and emergent public health priorities that all health professionals need to be aware of. Underlying all forms of discrimination are systems of categorisation, minoritisation and oppression; these may be manifest when considering matters of caste, colour, ethnicity, race, indigeneity, migratory status, religious faith and a multitude of other factors. The authors suggest that the root causes are motivated by efforts to maintain historic and existing power structures. In order to restore a sense of social justice, the authors emphasise the structural nature of racism and other forms of discrimination; they argue that we cannot address the consequences of racism, xenophobia and discrimination without an understanding, and weeding out, of the root causes.

Structural racism acts as a driver of racial and ethnic disparities in experiences and mental health outcomes.

Methods

The authors conducted a scoping review using Embase, MEDLINE, and PsychINFO across the study period, combining four umbrella search terms:

- Health outcomes, subcategorised into:

- Mental health

- Non-communicable disease

- Maternal and perinatal health

- Infectious disease

- Mortality

- Quality of care, subcategorised into:

- Health-care centred

- Patient-centred

- Mechanisms of action, including socioeconomic determinants of health

- Interventions that tackle health inequities from discrimination, with search terms relating to various forms of discrimination.

The authors only looked at reviews for evidence related to racism and discrimination based on migration, and took steps to avoid replicating the concentration of relevant literature in areas such as the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA).

Results

Contemporary definitions

Racism, xenophobia and discrimination are fundamental determinants of public health and have negative health consequences. These issues are associated with poorer mental and physical health outcomes (Paradies et al, 2015), and their effects have also been observed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Devakumar et al, 2020). The authors point out that discriminatory ideologies have historically shaped science and research. Ill health and health inequities are affected by these issues through structural factors (i.e., separation and hierarchical power) and their historical and political roots. Populist leaders and policies can exploit populations using racist, xenophobic, and discriminatory ideologies that lead to poor health. The authors argue that addressing these issues requires recognition of their complex and intergenerational nature.

A conceptual model

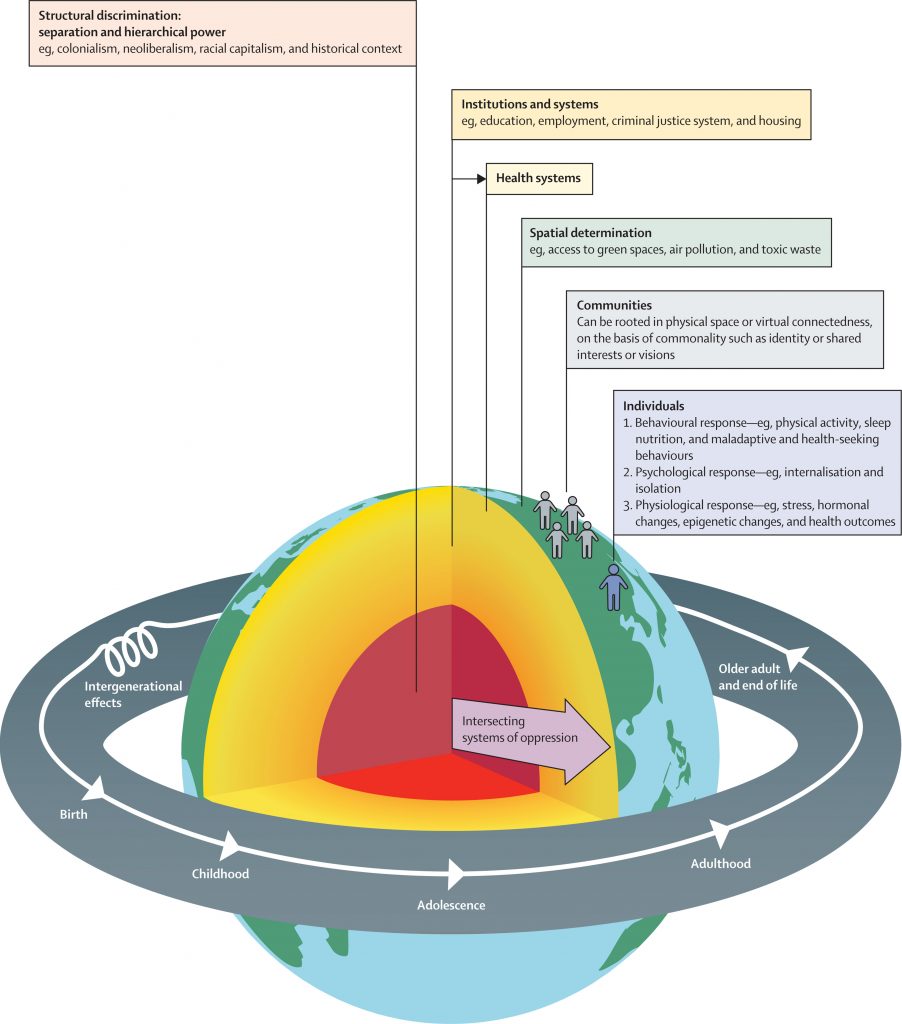

The authors propose a model for understanding how racism, xenophobia, and discrimination impact public health (see figure below). The model is based on six principles that recognise the active processes that determine health, the structural nature of discrimination, and the intersectionality of social categorisations. Discrimination affects individuals and communities through behavioural, psychological, and physiological responses throughout the course of life, and it can lead to health inequities through spatial and institutional determinants. At the broadest level, discrimination is enacted through structural processes such as laws, colonialism, racial capitalism, and exclusionary populism. The authors argue that public health has a responsibility to challenge and address these issues by centring antiracism, decoloniality, and equity.

The authors proposed this conceptual model for understanding how racism, xenophobia, and discrimination impact public health. [Click here to see full-sized figure]

Challenging the “inevitability” of increased mortality and morbidity

This section discusses how the timing of exposure to discrimination can impact health outcomes. Discrimination can occur at all stages of life, from preconception to older adulthood. Examples of discrimination over the life course include sexual assault, bullying, racial discrimination, and compulsory detentions of ethnically-minoritised individuals and migrants with mental health issues. The impact of discrimination is cumulative, hence can adversely impact older adults and end of life outcomes, including increased risk of being a victim of violence.

The authors further discuss the role of discrimination in determining health outcomes, particularly for minoritised groups, and the emerging understanding of neurobiological pathways that may provide clues to the pathogenic factors of discrimination. The authors argue that discrimination is a fundamental determinant of health, and that assessing discrimination scientifically can be complex and limited. They provide examples of health inequities, such as the higher maternal mortality rate among Black women in the UK and highlight the psychological effects of internalising discriminatory ideologies.

Understanding intersectionality

Intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, refers to how different systems of oppression like racism, gender, and class overlap and interact to create unique dynamics and effects that contribute to health inequities. This part provides five case studies from around the world to illustrate how discrimination and minoritisation are racialised processes and how racism is a form of structural violence. The authors argue that it is important to understand the historical and structural root causes of health inequities to effectively address them, rather than just focusing on improving access to services or health education, in isolation, for example.

Interventions thus far

This section discusses interventions needed to prevent and address the health effects of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination. The authors argue that a broader and deeper transformative action is required to dismantle existing political, economic, legal, and social systems that uphold and replicate racism and other forms of structural oppression. They suggest several specific actions, such as a commission to explore how to implement suggested approaches and building coalitions, expanding knowledge, highlighting inequities, and advocating for change. The interventions should target structural drivers of discrimination and consider the intersectional and generational nature of discrimination. The authors suggest that legal and human rights frameworks, and institutions and systems are also essential in preventing adverse health outcomes from racism. They call for more research to investigate the effect of various interventions that seek to prevent or address the consequences of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination on health.

Preventing and addressing the effects of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination will require concerted efforts.

Conclusions

This Lancet Series has sought to achieve four main aims:

- Building on the body of evidence to reinforce the importance of viewing racism, xenophobia and discrimination as public health priorities that all health professionals should be cognisant of.

- Addressing discrimination against minoritised populations due to the multiple and inter-related identities of caste, colour, ethnicity, race, indigeneity, migratory status, and religion.

- Situating racism, xenophobia, and discrimination as global health issues.

- Emphasising the structural nature of racism and other forms of discrimination.

The authors conclude with a call to action, whether supporting patients at an individual level, or advocating for national and international policy change.

Personal reflexivity and awareness of our own biases are critical to bringing change.

Strengths and limitations

The authors are to be congratulated on a wide-ranging and timely approach towards the issues of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination and their impact on health, including mental health.

Inherent in the nature of the study in this relatively nascent field is the element of subjectivity; the authors note the literature reviewed represents only a subset of more established scholarship on the health effects of discrimination, which is in itself limited by skewing of global research efforts towards the health needs of privileged groups and high-income countries (HICs), as opposed to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The authors also remark, quite appropriately, that “the absence of discrimination measured as exposure in academia does not mean the absence of discrimination in causing ill-health.” Regarding the centrality of knowledge production and scientific rigour, the authors further point out methodological limitations in the proportion of cross-sectional studies, which limits generalisability due to confounding and bias.

It is noteworthy that part of the review methodology avoided replicating the concentration of relevant literature in areas such as the UK and the USA; they are not monolithic, as evidenced by the fact that, while racism and structural racism has not been a well-supported area of scholarship in the UK, race-related and cultural psychiatric research in the USA and Canada attracts significant state, federal and research commissioner funding. A further limitation is the omission of grey literature, such as government publications and policy documents, which often provide context-specific data and analysis that can complement traditional published literature. Studies not published in English were not considered in the review, hence limiting the intended global coverage of the work.

Longitudinal and context-specific studies, utilising a range of implicit/explicit and direct/indirect measurement approaches, to capture intersectionality, represent potential future research opportunities to advance the field. Far from being limited, qualitative and mixed methods research can align with proactive, scholarly and pluralist approaches and make valuable contributions (Greenhalgh et al, 2016).

Intersectionality allows us to examine multiple processes simultaneously, it values diversity and respects multiple ways of knowing and knowledge production.

In the UK (compared to the US and Canada), race-related and cultural research is not a well-supported area of research in academia.

Implications for practice

The issues of racism, xenophobia and discrimination resonate deeply within my area of practice in Transcultural Psychiatry and with my lived experience of being a migrant to Australia, with the associated experiences of what it is like to be part of a minority group. Oftentimes in clinical practice, we may find that we have contributed to making a positive difference to our patient’s lives, but are left with the feeling that this is akin to a tiny drop in the ocean. I often wonder if the broader impact of healthcare professionals would be magnified by intervening at the wider levels of community and society, with more of an emphasis on preventative measures, rather than hoping for the prospect of (heroic) cure?

From the pioneering work of Frantz Fanon and the notion of Othering (i.e. The construction of differences between groups of humans and the differential allocation of power and resources to these groups, and the naturalisation of these differences through social hierarchies), there is now a need to shift the focus on experience-near research based on the humanities, arts and social sciences. Critical Race Theory (CRT), with its origins in American legal scholarship, provides one such example area of study from which we can develop an awareness of a framework for understand how race and racism intersect with other forms of oppression and shape the experiences of diverse peoples in everyday life; at the same time, we must be aware of the critiques of the theory and consider the implications, spectrum-wide, in deciding on practical application. The forthcoming Lancet Commission on Reparations and Restorative justice is also anticipated and will further contribute to the body of knowledge. Within Transcultural Psychiatry, we also recognise the significant impact of the social determinants of mental health (Shim and Compton, 2020). These are tricky areas of study, but one that I feel we are ethically and morally compelled to explore and continue the dialogue at this critical juncture in our history.

As healthcare professionals and clinicians, I would humbly persuade you that we can only seek to understand the root causes of discrimination if we cultivate a sense of personal reflexivity and critical thinking, as a start. In Australia, I would further propose adapting anti-discrimination approaches suggested internationally (Bracken et al., 2021), taking into account local contexts:

- Nurturing critical thinking amongst peers and trainees alike.

- A non-defensive and inclusive approach to teaching the history of Australasian Psychiatry, integrating Colonial, Indigenous and Immigratory influences.

- An openness to exploring non-Western ways of healing that complement existing and emerging evidence-based practices, noting the current value of Eastern-derived third-wave therapies.

- A move away from cultural competence training towards appreciation of the structural sources of health inequities.

- Clinical, scientific and pedagogical leadership aligned to advocacy and policy advancements, with relevant stakeholder involvement and engagement.

More than the knowledge, skills and attitudes that are cultivated through current discourse, an authentic valuing of the diversity of perspective and political will is essential to working towards better public health and the promotion of social equity.

As Albert Einstein famously said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” I would persuade you to consider this in terms of our broader humanity.

“An authentic valuing of the diversity of perspective and political will is essential to working towards better public health and the promotion of social equity.”

Statement of interests

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Devakumar, D. et al. (2022). Racism, Xenophobia, Discrimination, and Health. Lancet 400(10368): 2097-2108. [The paper is free to view, but you have to create an account on The Lancet website to gain access].

Other references

Napier, A.D.P. et al (2014). Culture and Health. Lancet 384: 1607-1639.

Abubakar, I. et al (2018). The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 392(10164):2606-2654.

Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., et al (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 10(9):e0138511.

Devakumar, D., Bhopal, S.S., Shannon, G. (2020). COVID-19: the great unequaliser. J R Soc Med 113:234-35.

Greenhalgh, T. et al (2016). An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ;352:i563

Shim, R.S. and Compton, M.T. (2020). Addressing the Social Determinants of Mental Health: If not now, when? If not us, who? Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ)18(1): 75-76.

Bracken, P., Fernando, S., Alsaraf, S. et al (2021) Decolonising the medical curriculum: psychiatry faces particular challenges. Anthropol Med 28(4): 420-428.

Photo credits

- Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

- Photo by Eden Constantino on Unsplash