It’s easy to become desensitised to truly shocking statistics when you live with mental illness or work in mental health. Every day we see headlines about the latest “crisis” or “epidemic” affecting people with mental illness, and yet life goes on for most of us.

Perhaps the starkest figures of all are those on suicide. About 6,000 people die by suicide every year in the UK, which means that someone takes their own life every 90 minutes. Of course, behind every one of those suicides is a complex story of pain and turmoil, love and loss, guilt and stigma.

We have blogged a lot about suicide prevention over the last few years, but very little of the evidence we’ve highlighted has focused on what happens in primary care. This is a problem because we know from research that about two-thirds of people who take their own lives aren’t in contact with mental health services in the year before they die (NCISH, 2018). However, a large number of people who die by suicide are in contact with their GP in the months before they die, with estimates ranging from 32-66% in the month leading up to their death and 75% in the 6 months before (Pearson et al, 2009; Saini, 2015; Leavey et al, 2017).

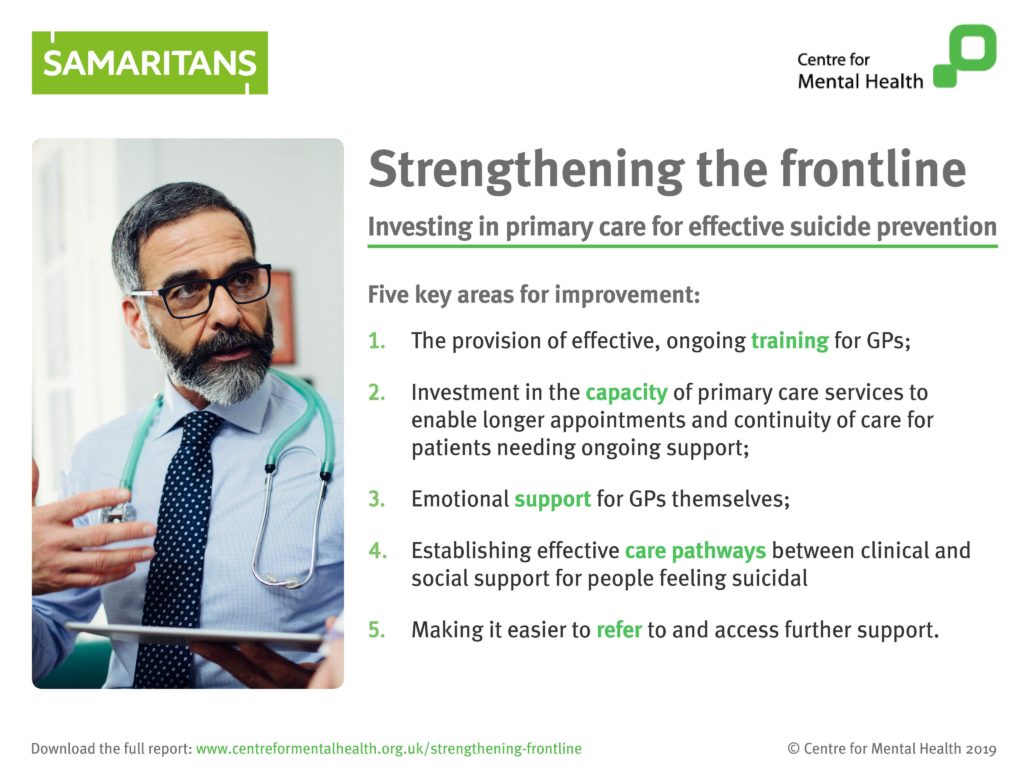

Centre for Mental Health and Samaritans have recognised the need for a summary of the evidence about suicide prevention in primary care, and have today published a report entitled: Strengthening the frontline: Investing in primary care for effective suicide prevention. The report is being launched at Westminster and you can follow the conversations on Twitter at #SuicidePreventionPC.

Most people who take their own lives aren’t in contact with mental health services in the year before they die, but many are in contact with their GP in the months before the suicide.

Methods

This report has been produced by Lauren Bear, Andy Bell and Jo Wilton from Centre for Mental Health, and Harriet Edwards, Carlie Goldsmith, Mette Isaksen and Jacqui Morrissey from Samaritans.

The team have used evidence from four sources to inform their recommendations:

- A literature review

- An online survey (completed by 38 people (82% female), which was completed by people who had visited their GPs when they were experiencing suicidal thoughts and feelings

- A ‘call for evidence’ which generated responses from 16 organisations and individuals involved in the field of suicide prevention

- Semi-structured interviews with 9 experts in suicide prevention and/or primary care.

Results

The report covers:

- Identifying and supporting people at risk of suicide (psychosocial assessment, safer prescribing, monitoring and follow-up)

- Embedding best practice in primary care (education and training, suicide awareness, clinical and communication skills, policy and procedures, postvention, safety planning, continuity of care)

- Empowering GPs to make use of best practice (supporting patients beyond primary care, professional and emotional support for GPs).

It’s short, very readable and has clear recommendations for government, policy makers and primary care.

Suicide prevention in primary care: areas of improvement

- Education and training: there is consensus that education is crucial to suicide prevention and that more needs to be done to enable GPs to access effective, ongoing training.

- Primary care practice and staffing: people told us that the therapeutic relationship between patient and GP needs to be a priority. However, many aspects of primary care, such as short appointment times and staff who are already working at full capacity, are not compatible with this.

- Emotional support for GPs: many GPs are not getting the support they need with their own emotional wellbeing, particularly following the death of a patient by suicide.

- Effective care pathways for people who are feeling suicidal: there is little evidence of effective pathways between primary care and both clinical and social support.

- Ease of making referrals and accessing further support: many GPs face considerable challenges referring patients on to further support. These include high thresholds for eligibility, variation in availability of services and lack of access to expert advice.

Recommendations

To address these issues, government should:

- Roll out evidence-based suicide prevention training for existing GPs on an ongoing and easy-to-access basis, and ensure that it is sufficiently covered in the curriculum for new GPs.

- Expand training for GPs so all trainees are given adequate exposure to patients who are at risk of self-harm and/or suicide, and are provided with the skills to recognise, treat and manage depression.

- Invest in emotional support services to ensure that all GPs have the support they need with their own wellbeing.

- Develop and evaluate care pathways for people with suicidal feelings and people at risk of suicide, as part of the implementation of the NHS Long-Term Plan and the national suicide prevention strategy.

- Direct social prescribing towards local areas with the highest rates of suicide as a priority, to improve access to social and community support for people experiencing suicidal thoughts and/or at risk of suicide.

- Ensure safer prescribing for people at risk of suicide, in order to improve and strengthen risk assessment by prescribers and to reduce access to potentially harmful medication.

Local policymakers, including Integrated Care Systems, should:

- Establish liaison arrangements with mental health professionals to offer guidance and support when GPs need specialist input for working with suicidal patients.

- Ensure primary care representatives and social prescribing link workers are represented in multi-agency suicide prevention groups and consult widely with these groups when determining priority interventions.

And GP practices should:

- Support continuity of care, monitoring and follow-up of people identified as being at risk of suicide by, for example, offering appointments with the same GP, establishing practice-wide policies on suicide prevention and actively seeking contact with at-risk patients who disengage.

Improving suicide prevention in primary care is possible, with evidence-based training, better therapeutic relationships, emotional support for GPs, effective care pathways, easier referrals to further support.

Conclusions

The report concludes that:

Urgent changes are needed to strengthen suicide prevention in primary care. The picture that emerged from our research is one that gives reasons for hope, while also demonstrating that much work remains to be done to ensure all at-risk groups and people experiencing suicidal feelings receive the support they so crucially need, when they need it.

There is a growing evidence base around suicide and what works to prevent it which provides a strong starting point for suicide prevention strategies. However, much more needs to be done to ensure this knowledge is having an impact on the day-to-day working of primary care, enabling GPs to more effectively support patients at risk of suicide.

Urgent changes are needed to strengthen suicide prevention in primary care.

Strengths and limitations

As always with reports produced by Centre for Mental Health, this is a very useful and practical document that sets forward a sensible and evidence-informed set of recommendations for action. The team have used a variety of methods to inform their recommendations and have ensured that the publication is usable for busy politicians, policy-makers and primary care professionals.

The methodology section of the report is very short, which is fine for a publication like this, as most readers don’t want to drown in database search strategies and the like. However, nerdy information scientists like me do appreciate links to appendices where this kind of information can be found. Ideally I’d like to see where and how they searched to retrieve the academic and clinical literature that went into this report, the survey questions and methodology, the methods behind the ‘call for evidence’, and also how the semi-structured interviews took place; i.e. how people were recruited, what questions were asked, how the findings were synthesised and written up.

Suicide prevention is a contentious field with considerable commercial interests, so evidence producers should always ensure that their publications have clear conflicts of interest statements and transparent methodologies.

Implications for practice

All of the recommendations included in this report seem sensible and evidence-based. The $6 million question is: Will this evidence reach the people who need it; those who can make the policy changes required to improve services for people at risk of suicide who present to primary care services?

The parliamentary launch today (follow #SuicidePreventionPC) is a good start, but this will have to be followed up by concerted action across government, policy-makers (including Integrated Care Systems) and of course in primary care itself, where time is always at a premium and there are plenty of barriers to implementing new approaches.

As is often the case in mental health, the solutions are not rocket science; they are about implementing evidence-based interventions (e.g. safer prescribing, safety planning), better training, more joined up working between primary care and secondary care or other community-based services (e.g. evidence-based referral options, access to social prescribing).

We will improve the lives of those affected by severe mental illness who are at risk of suicide if we improve therapeutic relationships between GPs and their patients. What’s happened to primary care over the last decade (shorter appointment times, little continuity of care, poorer communication, less tailored support) has conspired to make things worse. Systematic changes are needed in primary care if we are serious about preventing suicides.

Conflict of interest

I am a Trustee at Centre for Mental Health, but had no involvement in the production of this report.

Links

Primary paper

Centre for Mental Health (2019) Strengthening the frontline: Investing in primary care for effective suicide prevention.

Other references

NCISH (2018) National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide into suicide and safety in mental health. University of Manchester.

Pearson, A., Saini, P., Da Cruz, D., Miles, C., While, D., Swinson, N., Williams, A., Shaw, J., Appleby, L. and Kapur, N. (2009) Primary care contact prior to suicide in individuals with mental illness. Br J Gen Pract, 59(568), pp. 825- 832.

Saini, P. (2015) Suicide Prevention in mental health patients: The role of primary care (PDF). University of Manchester.

Leavey, G., Mallon, S., Rondon-Sulbaran, J., Galway, K., Rosato, M. and Hughes, L. (2017) The failure of suicide prevention in primary care: family and GP perspectives –a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), p. 369.

Photo credits

- Photo by Japheth Mast on Unsplash

- Photo by Pedro Gabriel Miziara on Unsplash