In the US, suicide is between the second and seventh leading cause of death for females of reproductive age (10-54 years) (Heron, 2019). Whilst individuals with depression and/or previous suicidal ideation (SI) are known to be at the most risk, SI can vary considerably over short periods of time (Kleiman et al., 2017). Research has therefore attempted to identify factors that impact acute risk amongst these groups. Possible risk factors have been identified, such as daily negative affect (Gee et al., 2020), hopelessness, and loneliness (Kleiman et al., 2017); however, it is challenging to establish whether these factors just correlate with SI or actually predict its occurrence. Moreover, these factors are similarly varying over time and, as such, are equally challenging to predict.

The menstrual cycle has been proposed as a possible acute risk factor for SI following cross-sectional evidence of increased hospitalisations during particular menstrual cycle phases (Saunders & Hawton, 2006). Menstrual disorders (Kuehner & Nayman, 2021), including premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and premenstrual exacerbation (PME), also suggest that the menstrual cycle could be a trigger for depressive symptoms, perhaps due to enhanced hormone sensitivity (Schweizer-Schubert et al., 2021). Prospective studies however are needed to understand how SI varies with the menstrual cycle amongst at-risk populations and to explore whether the menstrual cycle could be a useful, time-varying predictor of acute suicide risk.

This study aims to assess daily suicidal ideation (SI) and other affective symptoms alongside menstrual cycle phase to explore two hypotheses: (1) the perimenstrual phase will be associated with higher SI and affective symptoms than all other phases; and (2) the periovulatory phase will be associated with the lowest SI and affective symptoms than all other phases.

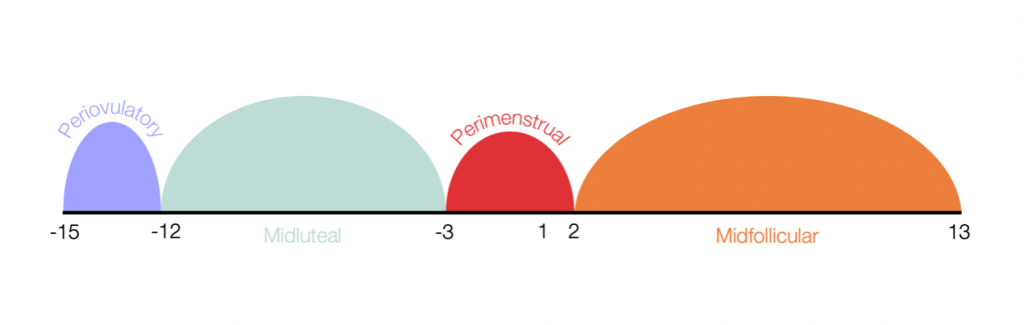

Previous research has suggested that suicidal ideation may fluctuate throughout different menstrual cycle phases [Figure by Sawyer (2023)]. View full size figure.

Methods

38 naturally cycling women with suicidal ideation in the past month responded to daily text messages asking whether they had menstrual bleeding that day. Based on this information, researchers applied forward/backward counting (Day 1 is first day of menstrual bleed) to calculate menstrual cycle phase:

- Periovulatory (Day -15 to -12),

- Perimenstrual (Day -3 to 2),

- Midluteal (all days between periovulatory and perimenstrual), and

- Midfollicular (all days between perimenstrual and next periovulatory).

Participants also rated seven items from the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire and eight items from the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (core symptoms of PMDD: depressed mood, hopeless, worthless/guilty, anxiety, mood swings, rejection sensitivity, anger/irritability, interpersonal conflict) each day. They were also asked to keep their medication use stable during the measurement period.

The researchers conducted multilevel regression to compare the daily suicidal ideation (SI) and affective symptoms of each participant between each of their own menstrual cycle phases (within-person analysis). Separate analyses were conducted to investigate whether pain influenced participants’ reported symptom severity but no substantive changes to the results were found.

Results

Hypothesis 1: The perimenstrual phase will be associated with higher suicidal ideation (SI) and affective symptoms than all other phases.

- The authors found that SI and all affective symptoms were higher in the perimenstrual compared with the periovulatory phase and all except worthlessness/guilt were higher in the perimenstrual compared with the midluteal phase.

- When comparing the perimenstrual with the midfollicular phase, only anxiety, mood swings, rejection sensitivity, anger/irritability, and interpersonal conflict were different (higher in the perimenstrual phase).

Hypothesis 2: The periovulatory phase will be associated with the lowest suicidal ideation (SI) and affective symptoms than all other phases.

- The researchers found that daily SI was similar between the periovulatory phase and the midluteal and midfollicular phases.

- Also, none of the affective symptoms differed between the periovulatory and midluteal phases.

- Depression, hopelessness, and worthlessness/guilt did differ between the periovulatory and midfollicular phases.

Overall, the models predicted that menstrual cycle phase could explain 25% of the variation in daily SI and between 10-30% of daily affective symptoms.

Menstrual cycle phase explained 25% of the variation in daily suicidal ideation and between 10-30% of daily affective symptoms in the 38 naturally cycling women studied.

Conclusions

This prospective study concluded that daily suicidal ideation (SI) (and other affective symptoms) are exacerbated by the menstrual cycle, peaking in the perimenstrual phase and reaching their lowest levels in the periovulatory phase.

Although this study explores longitudinal correlations, as opposed to causal relationships, it provides evidence that the menstrual cycle may be a predictable candidate risk factor for acute suicide risk, which could be utilised in clinical practice. In addition, it provides further justification for exploration of the causal relationship and underlying mechanisms.

The menstrual cycle could be a useful time-varying predictor of acute suicide risk amongst at-risk populations.

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by its use of prospective daily ratings, use of validated suicidal ideation (SI) and affective symptom measures, and the high response rate from participants (89% of possible daily ratings were completed). However, there are also a number of limitations that must be considered. Primarily, the observational nature of this study and the focus on longitudinal correlations means that conclusions about causality cannot be drawn from any of these findings.

The power of this study was limited by the small sample size (N=38), meaning only simple statistical models could be conducted. The sample may also limit the generalisability of the findings as it included only those with past-month SI but without a recent suicide attempt and primarily white participants with college-level education. Although participant medication use was held stable throughout the study, almost half of the participants were taking SSRIs (selective serotonin reupake inhibitors) which are an effective treatment for depressive symptoms and could therefore potentially reduce their variation across the menstrual cycle. Therefore, it is unclear whether the same patterns would be observed across different severity levels of suicide risk and within other demographic groups.

The measurement period was also relatively short (at least one menstrual cycle) and, although a longer measurement period may reduce the amount of daily ratings that are completed due to high participant burden, it would be useful to examine the relationship between daily suicidal ideation (SI) and menstrual cycle phase over a longer period of time.

This study is limited by the small sample size. The observational nature of this study means that conclusions about causality cannot be drawn.

Implications for practice

Primarily, this study provides implications for future research in this field by providing a strong case for further exploration of the menstrual cycle as an acute risk factor amongst women of reproductive age with ongoing suicidal ideation (SI), as well as identifying the mechanisms that may underlie the relationship. The authors of this study discuss hormone sensitivity as a possible mechanism, whereby subgroups of women have an abnormal reaction to normal hormonal changes that occur throughout the menstrual cycle. Whilst some research has supported the hormone sensitivity hypothesis (Pope et al., 2017), there are other promising mechanisms that should also be considered, such as inflammation and genetics (Tiranini & Nappi, 2022). Establishing how the menstrual cycle could impact SI and other affective symptoms could provide insights into possible treatment development to reduce the fluctuations in such symptoms.

However, as this paper is not able to make any causal inferences regarding the mechanisms through which SI and affective symptoms fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle, there are limited implications for practice at this stage. If future research provides support for the menstrual cycle as an acute risk factor for SI, then it may be useful for clinicians to consider the menstrual cycle when developing risk monitoring procedures and coping mechanisms with patients. Having an improved understanding of when SI severity may be at its peak will be useful for patients. This means support can be provided at appropriate times for women who experience these exacerbations.

The menstrual cycle may be useful for clinicans to consider in risk monitoring and when developing coping mechanisms with patients. Further research is needed however to understand how the menstrual cycle and suicidal ideation are related.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Owens, S. A., Schmalenberger, K. M., Bowers, S., Rubinow, D. R., Prinstein, M. J., Girdler, S. S., & Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A. (2023). Cyclical exacerbation of suicidal ideation in female outpatients: Prospective evidence from daily ratings in a transdiagnostic sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science.

Other references

Gee, B. L., Han, J., Benassi, H., & Batterham, P. J. (2020). Suicidal thoughts, suicidal behaviours and self-harm in daily life: A systematic review of ecological momentary assessment studies. Digital health, 6, 2055207620963958.

Heron, M. P. (2019). Deaths: leading causes for 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr70/nvsr70-09-508.pdf

Kleiman, E. M., Turner, B. J., Fedor, S., Beale, E. E., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of abnormal psychology, 126(6), 726.

Kuehner, C., & Nayman, S. (2021). Premenstrual exacerbations of mood disorders: findings and knowledge gaps. Current psychiatry reports, 23, 1-11.

Pope, C. J., Oinonen, K., Mazmanian, D., & Stone, S. (2017). The hormonal sensitivity hypothesis: a review and new findings. Medical hypotheses, 102, 69-77.

Saunders, K. E., & Hawton, K. (2006). Suicidal behaviour and the menstrual cycle. Psychological medicine, 36(7), 901-912.

Schweizer-Schubert, S., Gordon, J. L., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., Meltzer-Brody, S., Schmalenberger, K. M., Slopien, R., … & Ditzen, B. (2021). Steroid hormone sensitivity in reproductive mood disorders: on the role of the GABAA receptor complex and stress during hormonal transitions. Frontiers in Medicine, 7, 479646.

Tiranini, L., & Nappi, R. E. (2022). Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome. Faculty Reviews, 11.

Photo credits

- Photo by Towfiqu barbhuiya on Unsplash

- Figure by Gemma Sawyer

- Photo by Eric Rothermel on Unsplash

- Photo by Agê Barros on Unsplash

- Photo by LinkedIn Sales Solutions on Unsplash

- Photo by Gabrielle Henderson on Unsplash