This week, I heard a Radio 4 discussion with Dr Aseem Malhotra, a senior cardiologist, who has widely spoken of his concerns of an ‘epidemic’ and culture of overprescribing of medication, which can lead to a subsequent increased risk of adverse reactions in patients. This is in part because we (doctors or patients) can be ‘misinformed’ by poor quality, biased evidence within the pharmaceutical industry.

Statins in particular have been named as a ‘culprit’ who, if overprescribed, can have possible adverse effects. In this recent Cochrane systematic review by McGuinness and colleagues, the efficacy and safety of statins is considered, in their potential role as preventative drugs for dementia.

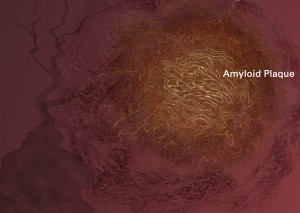

To recap, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, is related to build-up of amyloid plaques and β-amyloid peptide. Risk factors include cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease and hypertension, with some epidemiological studies showing mixed results for links between high serum cholesterol and increased rates of AD. Vascular dementia (VaD) is characterised by large and small vessel lesions and the risk factors are similar to those for vascular disease i.e. stroke, hypertension, diabetes, smoking and high cholesterol. Specifically, an association of VaD with decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL – ‘good’) cholesterol has been found, while the role of low-density lipoprotein (LDL – ‘bad’) cholesterol has remained controversial with research unclear as to its relationship with dementia risk.

Statins are prescribed for high cholesterol and for secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Given the above risks, it might be feasible to expect that statins, which specifically reduce LDL and increase HDL cholesterol, may help to prevent dementia. Initial evidence from observational studies was promising, but indication bias and heterogeneity of samples has been recognised to be a factor in these early studies.

As mentioned above, we also need to be aware of the possibility of adverse effects of statins, such as headaches, altered liver functions or gastrointestinal effects. Of note, there are even mixed results of a negative effect of statins on cognition and confusion, although these are generally not serious and stop after the medication is stopped.

The objective of this new Cochrane review by McGuinness et al (2016) was therefore to evaluate the efficacy and safety of statins for the prevention of dementia in people at risk of dementia due to their age. There was a secondary objective to examine whether this was dependent on cholesterol levels, genes (apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype) or cognitive level (not discussed widely here).

It has been suggested that high levels of cholesterol in the serum (part of the blood) may increase the risk of dementia.

Methods

Searches were conducted across ALOIS, a register of dementia studies maintained by the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, with some additional searches to ensure a comprehensive search.

Inclusion criteria

Double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trials in which statins were administered for at least 12 months to people at risk of dementia.

Outcomes

Primary: Objective diagnosis of dementia (AD; VaD); change in MMSE or another standardised test of cognitive performance; adverse reactions.

Results

Two studies (HPS 2002, PROSPER 2002) were selected. They included 26,340 participants, aged between 40 and 82 years old, with 11,610 aged 70 or older. All participants had a history of, or risk factors for, vascular events. The interventions were Simvastatin vs matching placebo (HPS 2002) or Pravastatin vs matching placebo (PROSPER 2007), with a mean follow up of 5 and 3.2 years respectively.

Incidence of dementia

Only HPS reported on the incidence of dementia. Of the 20,536 participants, there were 31 cases in each group (OR 1.00, 98% CI 0.61 to 1.65). The evidence was rated to be ‘imprecise’ (it was not made clear the criteria used to make this decision) and of only moderate quality.

Cognitive function

Although both studies assessed cognitive function, this was at different times with difference scales, so the results were not suitable for meta-analysis.

- HPS assessed cognitive outcomes using a Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-m) at final follow up. No significant difference was observed on the TICS-m between the treatment groups (MD 0.02, 95% CI -0.12 to 0.16, 20,536 participants, high quality evidence).

- PROSPER measured score on the MMSE, word recall on Picture-Word Learning Test, and time on the Stroop, across time points during the study. No significant differences were reported for change within the treatment groups.

Adverse effects

When data was combined in a meta-analysis, no significant difference was found for withdrawal rates between treatment groups (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.05), with 4.8/3.7% and 5.1/3.98% discontinuing due to adverse events for the treatment and placebo group respectively (HPS/PROSPER).

Quality of the evidence

The authors assessed the methodological quality of the trials using Cochrane’s tool for assessing risk of bias (GRADE). They found the quality of the evidence to generally be adequate and satisfactory with a low risk of bias.

Both studies assessed cognitive function, but at different times using different scales, so results could not be pooled in a meta-analysis.

Summary

The reviewers concluded that:

There is good evidence that statins given in late life to people at risk of vascular disease have no effect in preventing cognitive decline or dementia.

While statins reduce cardiac risks (i.e. reduced rates of stroke; HPS) and cholesterol (34% reduction in LDL cholesterol; PROSPER), there is limited evidence of a prevention of cognitive decline. Importantly, this group were an appropriate population to prescribe statins to (i.e. with vascular risks), and they showed no significant adverse risks, which is positive.

Unfortunately, only two studies were identified and these had cognition as a tertiary endpoint, and so they lacked true depth of change in cognition or incidence of dementia over time. Therefore, those in the early stages or with milder symptoms due to other protective factors may be missed.

Additionally, the follow-up was over a 3-5 years so it remains difficult to be conclusive about the protective value of statins in the longer term. This is particularly of interest because of the age of this population, between 40-80 (HPS) and 70–83 years old (mean age 75.4 years; PROSPER). Although they have vascular risks, they have yet to meet the age when their risk of dementia increases. A report by Dementia UK (2014) suggested that the population prevalence of dementia increases from 3% at age 70-74, to 6% at 75-79, to 11% at age 80-84 years and upwards with age. In order to gain an understanding of the impact of statins on those with the highest risk of dementia, either a longer follow up or different population sample would be required. Future RCTs should consider this, although as highlighted by McGuinness et al, there are financial pressures on high quality and long term RCTs.

The overall implications of this review suggest that statins can be tolerated in this population, but can be seen as evidence against any ‘myth’ that statins can be prescribed ad-hoc for the prevention of dementia. It supports the ideas presented by senior medical colleagues, that statins should be understood to be prescribed (at least for now) only for cholesterol reduction, to moderate any risk of adverse effects due to unnecessary overprescribing. In order to find ways to truly reduce the risk of dementia, I would be interested to see research that instead focuses on understanding the root causes of dementia, such as amyloid plaques, and how to prevent these, in order to inform future preventative treatment plans.

Amyloid plaques are sticky buildup that accumulates outside nerve cells, or neurons, which may hold the key for preventing dementia.

Links

Primary paper

McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003160. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003160.pub3.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003160.pub3/abstract

Other references

Dementia UK update: second edition. Alzheimer’s Society, 2014.

HPS (2002). Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20536 high-risk individuals: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360; 7-22. [PubMed abstract]

PROSPER (2007). Packard CJ, Westendorp RG, Stott DJ, Caslake MJ, Murray HM, Shepherd J, et al. Association between apolipoprotein E4 and cognitive decline in elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2007;11;17777-85. [PubMed abstract]

Statins for dementia prevention: well-tolerated, but Cochrane highlight lack… https://t.co/gHS2pvhtJU #MentalHealth https://t.co/AXSdbat2T7

RT @Mental_Elf: “Statins given in late life to people at risk of vascular disease do not prevent cognitive decline or dementia” https://t.c…

@cochranecollab find no evidence that #statins prevent #dementia https://t.co/b256diAP27

Don’t miss – Statins for dementia prevention: well-tolerated, but Cochrane highlight lack of evidence https://t.co/b256diAP27 #EBP

RT @mental_elf: Statins for dementia prevention: well-tolerated, but Cochrane highlight lack of evidence https://t.co/QpGjAF9kYq

Statins for dementia prevention: well-tolerated, but Cochrane highlight lack of evidence https://t.co/PwlKoNCwbe

Statins for dementia prevention: well-tolerated, but Cochrane highlight lack of evidence https://t.co/L9MRpKakyo