Crisis Resolution Teams (CRTs) for working-age adults have been implemented across England since 2000. Their aim is to treat those in mental health crisis at home, reducing the need for hospital admissions. A recently published national survey (Lloyd-Evans et al, 2018) produced a snapshot of the care provided by CRTs across England in late 2016, testing how far they reflect the model set out in the policy guidance for their implementation.

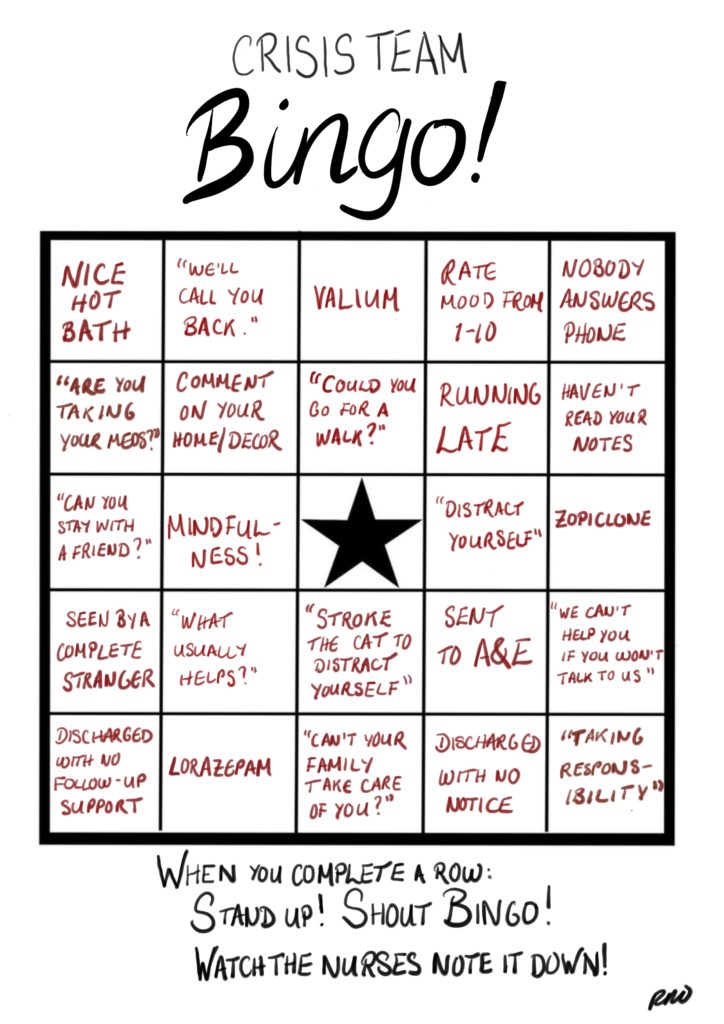

Crisis teams are not a well-loved intervention among service users and survivors: the common advice to have a bath and a cup of tea has become a running joke in online mental health communities; I made a Crisis Team Bingo Card based on my own and others’ experiences from the #CrisisTeamFail hashtag on Twitter.

The Crisis Team Bingo Card by Rachel Rowan Olive.

Methods

A 91-item questionnaire, involving a mixture of quantitative questions and questions requiring free-text responses, was sent out to CRTs, with a 95% response rate. This amounted to responses from 190 of 198 adult CRTs, 13 of 15 CRTs for children and young people, and 30 of 31 CRTs for older adults. Questionnaires were completed by team managers or senior staff.

Questionnaires mapped how closely CRTs adhered to policy recommendations for their implementation: this covered staffing levels, caseload size, referral and access arrangements, eligibility criteria, staff training and team philosophy of care, and the team’s role in “gatekeeping” hospital admissions. These metrics were compared to a similar set of criteria from a 2012 survey of CRTs.

Results

There is huge variation in how far CRTs adhere to the policy recommendations:

- Only 1% (one team) adhered to all the recommended staffing and access requirements

- Only 9% of CRTs adhered to all the recommended staffing requirements

- Only 42% had “easy referral processes” including accepting direct referrals from GPs, patients and families

- 69.5% of adult CRTs set a target for time to respond to a referral. 86% set a target for starting an assessment, but that target varied from 1 hour to 1 week. The median minimum number of visits per week to someone on the caseload was 2 for both adults and CYP, and 3 for older adults

- CRTs operate in widely varying acute care system contexts, with 32% of adult teams being ‘gatekept’ themselves via a separate triage/crisis assessment service; 22% having access to an acute day hospital; and 46% having access to residential non-hospital crisis beds.

When compared to the results from 2012, several things had changed:

- Provision of home visits 24/7 had increased from 39% to 69%

- Acceptance of self referrals from known patients increased from 55% to 69% and for new patients from 20.9% to 43%

- But the percentage of CRTs meeting minimum staffing requirements on the day of the survey had fallen from 87% to 76%. The 2016 level also dropped to 55% of teams when calculated on their reported highest typical caseload. However, the study authors note that this apparent decrease in staffing could reflect a higher response rate on the relevant questions in the later survey.

Conclusions

This study confirms the postcode lottery reported by service users in terms of access both to CRT care and to other crisis/acute care.

It also makes clear that top-down policy guidance is not enough to consistently implement an intervention; a conclusion familiar to any service user who has tried to access NICE-guideline compliant care.

This study confirms the postcode lottery reported by mental health service users in terms of accessing Crisis Resolution Teams and other crisis or acute care.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this paper is its high survey response rate, suggesting it provides a solid overview of how teams are (not) implementing the policy guidance. It provides a useful snapshot of CRT care. The question is what happens next with this information? (see the implications below).

A major limitation is the lack of data on CRTs’ ability to cater for those with specific needs relating to race or gender, for example. There is clear evidence that women with mental health problems are particularly likely to have experienced or be experiencing domestic and/or sexual violence (Khalifeh et al, 2014). It is important that this is reflected in research on teams like CRTs where service users may meet a large number of new staff very quickly, and where those staff may be making home visits: traumatised women are unlikely to respond well to a strange man coming into their home, even if they are wearing an NHS lanyard. Personally, it took several years and several crises to work out how to get my gender-related needs met; which need not have been the case if my local CRT had been able to anticipate that frightened women may have good reason to be more frightened of men. Given the recently much publicised fact that BME service users are disproportionately likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act (CQC, 2018), it would also be logical to look at what is going wrong in the community crisis care for this group.

It would therefore have been helpful to have a question in the survey on whether CRTs had a specific plan for meeting needs relating to gender or race. This reflects a broader issue where research on protected characteristics is often consigned to separate, focused studies; but to impact mainstream policy, they also need to be integrated into mainstream research.

Another limitation is the lack of data on how often CRTs were seeing people on their caseloads, or how long people were typically on their caseload for. Data was collected on whether teams set a target response time and the minimum number of visits per week; but there is no information on the extent to which these targets were met or the typical number of visits per week. The impact of greater accessibility for patients while teams have fewer staff is therefore unclear.

There is no information on any service user or survivor involvement in this paper. As a rule, this means there was either none or very little. I can’t help wondering whether co-producing the questionnaire with a diverse group of people might have anticipated some of these limitations. Relatedly, questionnaires were completed by team managers or senior members of staff who in practice are likely to have less contact with service users. For purely quantitative measures this is unlikely to have introduced bias, but it would be interesting to see whether service users and/or more junior staff gave the same responses as a manager on whether the team works to a named model, for instance.

Finally, there is a limitation inherent in using policy guidance as the starting point, which takes as read the idea that conforming to said guidance is positive. But the priorities of policy makers are not necessarily those of service users and survivors. For instance, my experience of CRTs’ “gatekeeping” role for hospital admissions has been negative, appearing focused on services’ need to reduce bed days rather than on my needs. It has generally meant making a plan when acutely distressed with either the Emergency Department Psychiatric Liaison or my regular care team, only to have to go through another assessment with a stranger from the CRT who may or may not confirm it. This process is disempowering and on occasion has left me quite unsafe. It is important for this survey to be backed up by more qualitative research to investigate the relationship between adhering to CRT policy guidance and providing meaningful support.

It would have been helpful to have a question in the survey on whether CRTs had a specific plan for meeting needs relating to gender or race.

Implications

There are implications for both policy and research.

The clearest implication for research, highlighted by the study authors, is that more information is needed:

- firstly, on the care system context in which crisis teams operate;

- secondly, on the care CRTs are actually providing and how effective this is, for all three age brackets;

- thirdly, on the impact of apparently providing greater access to CRTs when fewer are meeting minimum staffing requirements;

- and fourthly, on any measures to improve the implementation of CRTs.

I believe there is a need to ground future research in existing knowledge around race and gender, and for quantitative data to be backed up by solid qualitative research which can place them in the context of service users’ experiences.

The variability of CRTs’ implementation has implications for the evidence base of much clinical practice. From my perspective as a service user, I wonder how my care can truly be evidence-based, when so much is clearly lost in translation from policy to practice.

How can my care truly be evidence-based, when so much is clearly lost in translation from policy to practice?

Conflicts of interest

No formal conflicts of interest. However, Rachel is a member of the Lived Experience Working Group for UCL’s Mental Health Policy Research Unit. Prof Sonia Johnson and Dr Bryn Lloyd-Evans are the director and deputy director of this unit respectively. Membership of the working group has not to date involved working on papers authored by either.

#MHNR2018 conference

Prof Sonia Johnson is giving a keynote talk at the #MHNR2018 conference in Manchester today. She is also featured on the conference podcast featured below.

Links

Primary paper

Lloyd-Evans B, Lamb D, Barnby J, Eskinazi M, Turner A, Johnson S. (2018) Mental health crisis resolution teams and crisis care systems in England: A national survey. BJPsych Bulletin, 42(4), 146-151. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2018.19

Other references

Khalifeh, H., Moran, P., Borschmann, R., Dean, K., Hart, C., Hogg, J., . . . Howard, L. (2015). Domestic and sexual violence against patients with severe mental illness. Psychological Medicine, 45(4), 875-886. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714001962

Care Quality Commission (2018) The Rise in the Use of the MHA to Detain People in England (PDF).

Photo credits

- Peter Ward CC BY 2.0

- The Crisis Team Bingo Card by Rachel Rowan Olive.

- Photo by dylan nolte on Unsplash

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

Thanks for your interesting blog. Understaffed Crisis Resolution & Home Treatment Teams will respond to individuals in a variety of ways- sometime helpful, sometimes not. Their skill sets will also vary. I recognised your Bingo Card of responses…

I believe that a key issue is that these services lack a coherent overarching philosophy to guide practice. Many managers focus on throughput and want these teams to act as little more than ‘medication delivery services’ and to just provide short-term advice and support. Unfortunately few CR&HTTs work to the original systemic philosophy of care (cf. service developed in Barnet, London in the 1970s; theoretical papers by R.D. Scott) and very few services recognise the importance of developing therapeutic relationships with the person seeking help and their support network. The mental health service in Western Lapland, Finland, provides a good model for what CR&HTT could become- they provide an immediate intensive response to the individual/ support network and maintain this therapeutic relationship. In effect the small CR&HTT which is formed in each case then coordinates the care package. Their outcomes appear to be excellent and their more responsive model of care also works out cheaper than our services which are structured around different mini-services with their separate waiting lists. Services based on this ‘Open Dialogue’ model of care are being trialled in the UK and internationally and hopefully this model will become more widely available in the future.

I’ve just purchased A is for Awkward, so apt. I totally agree with your views as a service user with PD.