People in England and Wales with an active mental health problem, who are considered to show signs of risk to themselves or others, located in a public space, are sometimes apprehended by police and brought to a safe place under the auspices of the Mental Health Act for assessment and treatment. The power to do this is defined in section 136 of the Mental Health Act. Detention by police, conveyance to a designated 136 “suite”, lengthy assessments by nursing, medical and social care staff, and ensuing use of inpatient care, is extremely costly and labour-intensive, and tends to be reserved for the most acutely unwell people.

In 2013, the then Care Minister Norman Lamb announced several regional pilots of “street triage”, with a view to improving the experiences of people with mental health needs who end up interacting with police and caring professions (Department of Health, 2013). Street triage is a strategy to reduce 136 admissions, which involves having a mental health professional, typically a nurse travel with police officers and assess people, who might otherwise be candidates for 136 arrest, and instigate treatment.

March 2016 saw the publication of an NHS commissioned evaluation of the nine pilot schemes in England, which included quantitative and qualitative data analysis (Reveruzzi & Pilling, 2016). This evaluation concluded: “All but two of the nine Street Triage schemes resulted in a reduction in the use of s136 detentions, when compared with an equivalent timeframe from the previous year.”

The study that is the focus of this blog, published in BMJ Open in November 2016, quantitatively describes a street triage service in the North East of England, and the effect that this service had on the use of section 136 in that region (Keown et al, 2016).

Methods

The investigators present data on a street triage service that was established in the Northumberland, Tyne and Wear in September 2014. They examined street triage engagements in the first year after starting the service, and report uses of the 136 power for the same period, and use the same information for the year prior to September 2014 for comparison. Because the implementation of street triage was staged, starting first in the South of Tyne area, researchers make comparisons between 136 use in areas where street triage was in use with those areas where it had not yet started.

Data on admissions and uses of other Mental Health Act powers is also presented. Rates of street triage engagement are reported, based on estimates of population at risk from the Office for National Statistics.

Street triage involves health professionals working with police officers in responding to suspected mental health problems that present in public places.

Results

- The investigators found that use of Section 136 in the study area went down throughout the whole trust

- During first year, the rate of street triage was 138.7 per 100,000 people in the population

- The rate of S136 detentions fell:

- from 59.8 per 100,000 population prior to the introduction of street triage,

- to 26.4 per 100,000 in its first year,

- a reduction of 55.9%

- Areas with more street triage engagements also experienced greater reductions in 136 rate

- Closer examination of street triage areas where a year of data was available, suggested that the reduction of 136 use was spread throughout the year

- Against the background of rising accident and emergency (A&E) attendances throughout the trust in this period, 136 assessments in A&E also fell

- Outcomes of 136 assessments did not change over the study period.

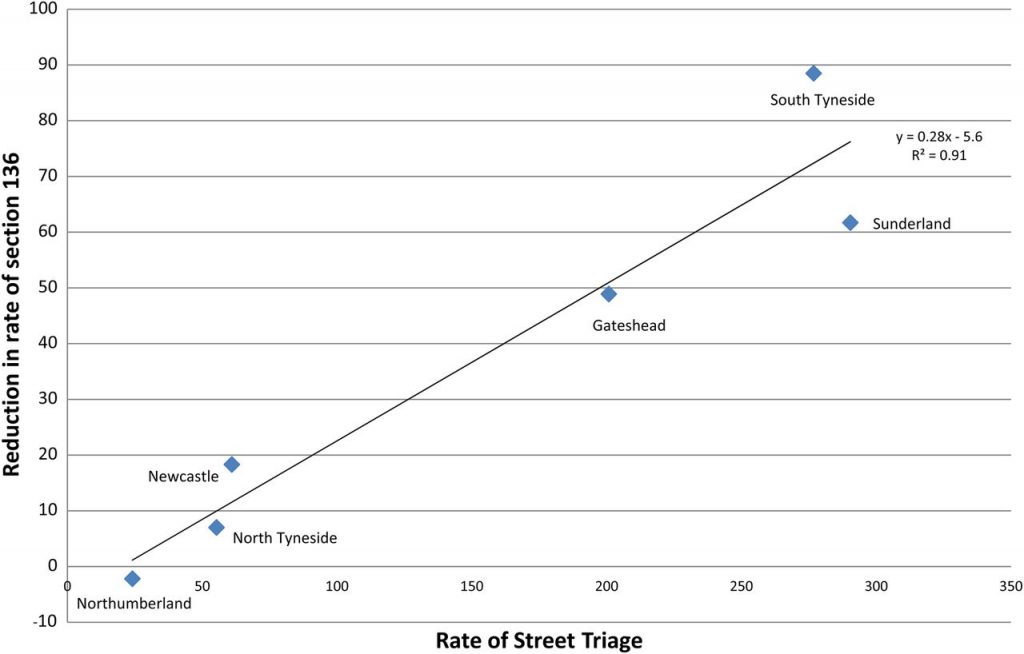

Reproduced from the paper, the authors show this scatter plot of reduction of 136 rate against the rate of street triage, based on six areas in Tyne and Wear:

Rate of street triage contacts and reduction in rate of Section 136 detention per 100 000 population in the six localities Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust. Data are the first year following the phased implementation of street triage in 2014/2015 when street triage first started operating South of Tyne (South Tyneside, Sunderland and Gateshead) and 10 months later started operating North of Tyne (Northumberland, Newcastle and North Tyneside). Figure reproduced from BMJ Open paper.

Conclusion

The authors conclude:

Street triage leads to a reduction in 136 detentions.

Strengths and limitations

Indeed, the analysis is based on a large, densely populated geographic area, with a high background rate of 136 use. Statistical hypothesis testing suggested large differences in 136 rate in the before versus the after period. Given that 136 did not fall in areas where street triage was not happening, an effect of street triage on 136 seems plausible, under the assumption that nothing else important changed in those particular areas over the study period, that might have affected the occurrence of 136 detentions.

However, this assumption doesn’t seem to be covered in much detail in the paper. What information there is in the paper, indicating that one 136 suite closed during the study period, might be expected to reduce the detention rate on its own, although possibly not enough to account for the extent of change observed in this analysis.

Although the geographical area is large, the rate across six units is analysed, limiting statistical power. It is possible that had other units from neighbouring regions been sampled in the study, the association might have been different. There isn’t a great deal of information on measurement in this study; for example were street triage engagements more likely to be recorded correctly in areas with lots of police activity?

There are also important issues with generalisability here. There was not much description of the street triage intervention, so we do not know how this may be different to street triage in other areas, including how it was experienced by patients and the public. Finally, this study did not randomise units to the intervention, and there were only 6 units analysed, so we cannot be sure that it was street triage that was having the effect, and not other background factors. This means that the use of the quantity “number needed to triage”, which assumes a causal effect, is premature. However unlikely it might be, confounding factors that resulted in a reduction in 136 activity cannot be discounted as a cause for these results. Furthermore, it is very unclear how the changing demographic, local policy, and mental heath landscape might have influenced the results.

The methodology of this research means that we can’t be sure the reductions in section 136 activity are a direct result of the street triage work.

Implications

The main implications for this study are for research. Reducing section 136 use would appear to have been treated as an adverse outcome in this study, but is that necessarily true? Research on 136 needs to broaden out to adopt a variety of different approaches, with an emphasis on routine data and the experiences of patients. This must take the form of better descriptions of who is detained using this Section and for what reasons, in order to identify what reasonable clinical outcomes we should be measuring.

In clinical practice, we see many patients who, without the use of 136 powers, would not have seen a clinician until much further into an episode of illness. In a resource-poor NHS, how realistic it is to comprehensively roll out mental health staff to accompany police officers remains to be seen.

Research on 136 needs to broaden out to adopt a variety of different approaches, with an emphasis on routine data and the experiences of patients.

Links

Primary paper

Keown P, French J, Gibson G, et al. (2016) Too much detention? Street Triage and detentions under Section 136 Mental Health Act in the North-East of England: a descriptive study of the effects of a Street Triage intervention. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011837. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011837

Other references

Mental Health Act 1983: Section 136.

Department of Health (2013) Extending the street triage scheme: new patrols with nurses and the police.

Heslin M, Callaghan L, Barrett B, et al. (2016) Costs of the police service and mental healthcare pathways experienced by individuals with enduring mental health needs. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2016: bjp. bp. 114.159129.

Reveruzzi B, Pilling S. (2016) Street Triage Report on the evaluation of nine pilot schemes in England (PDF). Department of Clinical, Health and Educational Psychology, University College London

Most ‘street’ triage doesn’t happen in the street – what’s going on with the 55%-75% of encounters where s136 is simply not possible, legally speaking?

Most street triage encounters do not involve nurses meeting patients – many schemes involve the nurses working remotely in police control rooms and only undertaking face-to-face assessments in a minority of cases. That remains true even where schemes have a double-crewed car involving a nurse with an officer.

No-one seems to be asking the question about why the police were contacted and where the calls were coming from. In my evenings of shadowing street triage, 46% of the incidents were generated by the NHS itself, lacking the capacity in OOH GP services, community or crisis teams to respond to patient needs and deflecting demand to street triage ‘because the police have nurses now’. So we don’t know whether the demand faced would have been faced by the police if ST did not exist.

There appears to be little discussion of funding and resources: some models of street triage could easily be shown to involve the Chief Constable having to at least double the officer hours spent handling that original demand, plus whatever extra may or may not be generated by the initiative. And yet despite this, in some operating models, it is the police paying for the nurses, though funds often controlled by the Police and Crime Commissioner.

Finally(!), there seems to be no discussion of civil liberties and as your rightly point out: no evaluation to date has really touched qualitatively on patient experience. Some schemes who have sought to publicise their work, have shown themselves to be acting in an ethical dubious way – detaining people and subjecting them to coercion and ‘de facto’ detention, to create the time and space for ST schemes to get involved in advising or assessing. There is no legal power to ‘detain someone pending triage’.

I thank you for this short piece – it adds to the questions and demands further answers.

It’s mentioned how realistic it would be for the NHS to roll out mental health staff to police forces, but iirc, the police are funding the MHPs they’re using for both Street Triage and control rooms, not the NHS. I think there is even an issue where some constabularies are relying on volunteer MHPs to fill gaps in the rota because they can’t afford to employ somebody. Unless I’m wrong, it would seem the NHS is already unwilling to fund Street Triage…

[…] Street triage: all it’s cooked up to be? […]

Great blog. thanks for raising some important points.

As a patient who has been detained by Street Triage it’s hard to see reduction in s136 focussed on as the primary outcome by research studies. It’s also hard to see patient voices so excluded from research analysis, but conclusions about roll out of ST already made.

With ST, it seems there are lots of good people involved, with good intentions, and trying to help, but research so far hasn’t considered or asked what outcomes matter to patients. Detention under s136 is presumed a bad thing, but it can be lifesaving. It can also be a better outcome than a de facto detention as happened to me with ST, without any legal protection. I was held by police for several hours while ST took time to arrive and then interviewed me, preventing from leaving, but without any rights or the legal protection of the Mental Health Act as would have happened if s136 had been used. Police being part of the ST team that comes out also meant that everyone passing by saw that I was being interviewed by police.

Inspector Brown’s comment about who calls ST and why is one that needs more consideration. We need to look at causes, not causes of ST fluctuation, but causes of ST ‘demand’. Are ST coming out because they are the best service, for me, at that time, or because they are the *only* service?

Does the existence of ST teams mean police are now attending jobs they wouldn’t have without ST? Every contact with police in mental health crisis has potential to have unintended adverse consequences for the person which the research studies on ST so far appear not to have taken into account. In a time of limited health resource, does spending on ST teams reduce future crises or alleviate suffering or even risk, or does it displace mental health crisis spending from health to criminal justice?

Outcomes I’d like to see measured in crisis are whether an intervention resulted in me being able to access both crisis and follow up help. Whether I’m still alive and unharmed, including psychological harm caused by interventions. What the risks and harms were to me from the intervention, and what my experience of it was. Also the experience of my friends or family who may have initiated concerns.

ST may be the right service for mental health crisis, but it’s hard to see that conclusion being drawn when the outcomes that matter to me don’t feature in analyses and nobody has asked people like me who have experienced it what impact it had, and still has, on us.

Paragraph 4 should read:

*not causes of s136 fluctuation, but ST demand

Actually Street Triage isn’t simply about reducing The number of S136 detentions, it was always about reducing the number of inappropriate detentions. Within this locality, prior to Street Triage being operational approximately 65% of people detained on a 136 were subsequently discharged home, without the need for any psychiatric follow up. And now, around 65% are admitted to hospital, indicating the use of 136 detentions is used far more appropriately.

However, Street Triage does much more than focus on 136s, in fact it could be said that in his area, 136s are old news. This particular Street Triage team only takes referrals from police, though there are a number of models in operation in the Uk.

I agree we do need to gain service user feedback and that’s something that currently being looked into.

As for asking if ST come out because there’s no other team available, our crisis teams work 24/7, but if a person comes into contact with the police and it is thought there is a mental health component to the contact, then ST go out and see the person.

I would have huge concerns if any of the people seen by ST were coerced into doing so, or illegally detained until they were seen and I think this needs further exploration.

I must add that I do have a vested interest in this Street Triage Team, as I’m the team manager for the ST team you’ve discussed.