Depression and dementia are inextricably linked in my mind because my mother was diagnosed with both a few years ago; depression in 2010 and dementia in 2011. According to the timing of her diagnoses at least, depression came first.

A recent study by Mirza et al (2016) published in The Lancet Psychiatry with an accompany editorial (Reppermund, 2016) suggests that older people whose depression symptoms increase over time are at increased risk of developing dementia. According to the authors of this study, they come closer to establishing whether depression is a risk factor for dementia, or vice versa, because they follow a group of people with depressive symptoms over time, rather than assessing them at one time point.

The authors suggest that this is the first long-term study to assess the course of depression in relation to dementia risk.

Methods

The researchers carried out a study within a study, using people who were already enrolled in The Rotterdam Study; a population-based study of adults over 55 which has been ongoing since 1990.

The participants were people selected from the Rotterdam Study who had recorded depressive symptoms at one or more of three examination rounds in the mid-1990s, the late 1990s and the early 2000s, but had not shown symptoms of dementia. Using these criteria, the study included 3,325 people.

At each of the three time points between 1993 and 2004, potential participants were assessed to measure the severity of their depressive symptoms. During the third examination round they were also assessed for an array of other factors associated with depression and thought to be risk factors for dementia which gave the full baseline characteristics for the final cohort. These included APOE4 allele carrier status, educational level, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, cognitive score, use of antidepressants and disease status, including high blood pressure.

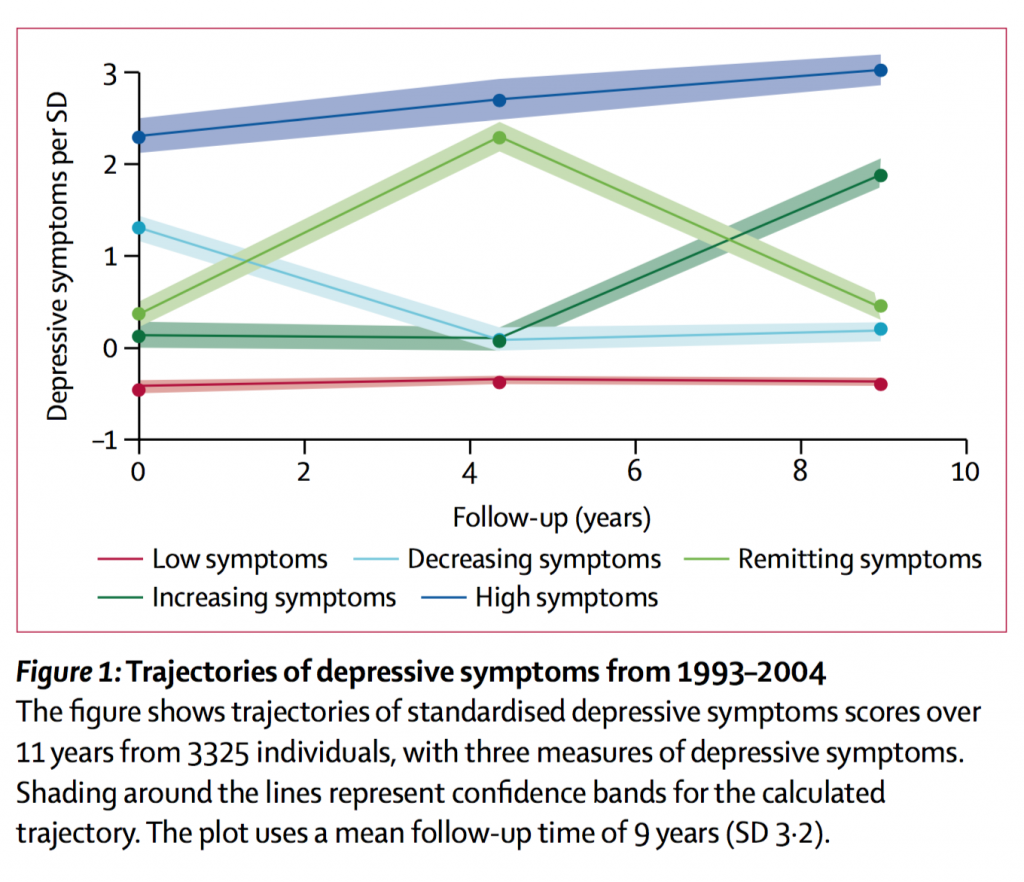

The data about their depressive symptoms gathered over the 11 years led the researchers to identify five trajectories of depressive symptoms. They illustrated these trajectories in what I was amused to learn is called a “lasagna plot”. And yes, since you ask, lasagna (shouldn’t it be lasagne?) is an alternative to spaghetti in the graphical display of longitudinal data. They have to make their own entertainment, these epidemiologists.

The five trajectories of depression symptoms and the numbers in each group were as follows:

- 2,441 (73%) had consistently low symptoms

- 369 (11%) had symptoms which decreased over time

- 170 (5%) had symptoms which decreased and then increased

- 255 (8%) had symptoms which increased over time

- 90 (3%) had consistently high symptoms

After the last examination round in the early 2000s, the participants were followed up for 10 years to track incidence of dementia. The follow-up examinations included home interviews and physical examinations at a research centre every 3-4 years plus continuous monitoring for major events via the Rotterdam Study database and their GPs.

Results

The 255 people in the group who had symptoms of depression which increased over time seemed to be at higher risk of developing dementia compared with the reference standard of people with consistently low symptoms.

Here are the numbers who developed dementia in each group, and the hazard ratios (HR) and confidence intervals (CI):

- 281/2441 (12%) with consistently low symptoms reference standard (HR 1.00)

- 52/369 (14%) with decreasing symptoms (HR 1.06; CI 0.79 to 1.44)

- 27/170 (16%) with remitting symptoms (HR 1.22; CI 0.82 to 1.82)

- 55/255 (22%) with increasing symptoms (HR 1.67; CI 1.24 to 2.24)

- 19/90 (21%) with consistently high symptoms (HR 1.50; CI 0.94 to 2.41)

The main conclusion drawn from this study is that the findings are consistent with the hypothesis that depressive symptoms in older age may represent an early stage of dementia. It is also consistent with the suggestion that depression and dementia might be manifestations of a common cause. So no surprises there.

There was no distinction made between different types of dementia which is frustrating as Alzheimer’s disease dementia and vascular dementia, for example, have different causes and therefore will have a different relationship with depression.

I also find it interesting that the trajectory is described as people with symptoms which gradually increase over time. According to the lasagna plot, the people on the increasing symptoms trajectory have low symptoms for the first two examination rounds, and then high symptoms in the last round. If it were a gradual increase, then the lasagne wouldn’t have a big hole in the middle.

This study shows that depressive symptoms that steadily increase in later life predict higher risk of dementia.

A personal perspective

As I mentioned at the start of this blog, my mother was diagnosed with depression in 2010 aged 83. This was the year when having been an active and energetic woman still doing a huge amount of voluntary work, and very rarely physically ill, she became cognitively and physically impaired almost overnight. It turned out that she had suffered a series of mini-strokes. Unsurprisingly, her mood was low. She was prescribed various antidepressants which didn’t help her, one of which is known to impair cognition; great job medicos! It was only through my intervention that she eventually got a diagnosis of vascular dementia over a year later. The antidepressant medication was continued however but thankfully changed and reduced in dose over the subsequent years of her illness.

The timing of diagnoses and treatment was driven by the emotional symptoms of depression which were ‘acceptable’ to her and her family at the time, and ignored the symptoms of dementia which were taboo.

If my mother had been in the Rotterdam Study (which incidentally she would have loved) I am not sure she would have been identified as having any depressive symptoms at all, so would not have been included in this study. She had symptoms of anxiety and depression throughout her life, but like many others of her generation, she was unlikely to seek help for non-physical ailments so there would be no record of it.

On a more upbeat note

However, this study must hold hope for present and future generations who are more willing to seek help with anxiety and depression. We can use the knowledge from this and future studies to continue to try and unravel the complex causes of dementia, and develop strategies to lower our risk of developing it if we can.

This research supports the theory that depression and dementia may both be symptoms of a common underlying cause.

Links

Primary paper

Mirza SS, Wolters FJ, Swanson SA, et al. (2016) 10-year trajectories of depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: a population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; published online April 29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00097-3.

Other references

Reppermund S. (2016) Depression in old age: the first step to dementia? The Lancet Psychiatry http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30022-0

The Rotterdam Study is a population-based study of adults aged 55 years or older in Rotterdam (Netherlands), ongoing since 1990. Its aim is to investigate factors that determine the occurrence of cardiovascular, neurological, ophthalmological, endocrinological, and psychiatric diseases in elderly people. http://www.erasmus epidemiology.nl/research/ergo.htm

RT @Mental_Elf: Don’t miss: Depression may be an early symptom of dementia https://t.co/bcMvnnRFsY #EBP

RT @Mental_Elf: #Depression may be an early symptom of #dementia

https://t.co/bcMvnnRFsY

Pls RT study in @TheLancetPsych https://t.co/RPLaR…

RT @PacificCove: Depression may be an early symptom of dementia https://t.co/XlMtd8JZez

Depression may be an early symptom of dementia https://t.co/KoAFqgf5I9

Depression may be an early symptom of dementia https://t.co/jngwR6OEMr

[…] Depression may be an early symptom of dementia- Mental Elf Blog post. […]

[…] Depression may be an early symptom of dementia […]

Another great @Mental_Elf blog- Depression may be an early symptom of dementia https://t.co/QkoLrdEkCe via @sharethis

[…] Depression may be an early symptom of dementia […]