Over the past 4 years, I have spoken to well over 200 schools about the mental health and wellbeing provision in their school. Many of them talk about the Mindfulness sessions that they have built into the school day. How this is delivered can vary enormously from a 2 minute YouTube video, to app-based activities, to all teachers receiving formal training and being given time explicitly to deliver sessions. But does it work?

This blog will look at the results of the MYRIAD (My Resilience in Adolescence) Project, the largest Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial to research the impact of a school-based Mindfulness intervention on the mental health of young teens. It is a review of 7 papers published in a special issue of the Evidence Based Mental Health journal. The papers draw together a range of findings from the trial that not only focus on the intervention’s efficacy, but also the implications of the findings for universal interventions delivered in schools and what has been learned about how mental health interventions are researched.

There are seven new papers out today on the MYRIAD trial. This blog focuses on the methods and findings from the main trial (see the complete list at the end of this blog), but will make reference to other papers.

Mindfulness in schools is now commonplace, but does it work?

The Myriad Project

Meta-analyses of the research into mindfulness as a universal intervention delivered in schools to young people has so far suggested that it has positive outcomes. However the initial research done at the start of this project suggested that this research was of poor quality and so this trial set out to produce high quality, robust evidence on the effectiveness of a schools based mindfulness training intervention at a universal level.

Delivery of such a programme seems intuitively the right thing to do. Research has suggested that mental health amongst our young people is getting worse and so teaching them skills such as those in mindfulness training will support their mental health in a cost effective and easy to administer way. Not only this but by making it universal it reduces the stigma which can be a barrier to young people accessing targeted interventions. Whilst these universal interventions may not have a huge impact on wellbeing, they may just shift the normal distribution of mental health in a positive direction – just a little.

Methods

The main trial of the MYRIAD Project was a cluster (schools) randomised controlled trial. Schools were recruited across two academic years 2016/17 and 2017/18. Schools were eligible if they had a substantive appointed headteacher, had not been judged inadequate in their last inspection and had an adequate Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) Curriculum in place. In total, 85 secondary schools were recruited that were broadly representative of schools in the UK (i.e. selective/non-selective, small/large, co-educational/single sex etc.).

Schools were then randomised into the control arm (TAU: teaching as usual) or the trial arm (SBMT: School based mindfulness training). For both arms, the allocation of schools was balanced on variables such as region, type of school (boys, girls, mixed) and deprivation. There were 43 schools (N=3,678 students) in the SBMT arm and 42 schools (N=3,572 students) in the TAU arm. Each school also chose 15 teachers to start the personal mindfulness training with 5 of these going on to do the SBMT curriculum, only a proportion of whom would go on and teach the curriculum to students.

The SBMT comprised of 10 structured lessons (30-50 minutes in length) normally delivered over one term. It introduced students in either years 7 or 8 (aged 11-13) to a range of skills such as self-regulation of thoughts, feelings and behaviours. All sessions were recorded and assessed for quality. In the TAU arm of the trial all schools offered some form of SEL provision covering topics such as relationships, sex education and physical and mental health.

The outcome measures were measured at an individual level at school consent, pre-intervention, post-intervention, and at 1 year follow-up. Students completed the following co-primary outcome measures of:

- Self-reported risk for depression (Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression Scale; CES-D);

- Self-reported social-emotional behavioural functioning (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SDQ, Youth Self-Report Version, total difficulties score);

- Self reported well-being (Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale; WEMWBS) at the 1 year follow-up primary time point.

Also secondary outcome measures at post-intervention and the 1 year follow up of students’ executive function, self-reported drug and alcohol use, self-reported anxiety, teacher-reported social-emotional-behavioural functioning, self-reported self-harm and suicidal ideation, school climate, and self-reported mindfulness skills. Risk for depression, social-emotional-behavioural functioning and well-being post-intervention were also secondary outcomes.

Teachers also completed outcomes measures assessing their mental health and wellbeing, looking at teachers’ burnout, self-efficacy, mindfulness, mindfulness in teaching, stress, depression and anxiety. Teachers also reported on school climate which was assessed with the School Climate and Connectedness Survey, using three scales most relevant to SBMT: ‘School Leadership and Involvement,’ ‘Staff Attitudes,’ and ‘Respectful Climate’.

Finally teachers’ engagement with the SBMT was assessed in two ways:

- Their personal mindfulness training was assessed through two self-report items asking about the frequency of formal (structured) and informal (flexible) mindfulness practice.

- The extent to which participating teachers completed the full training/implementation route of the SBMT was recorded.

Results

There are a wide range of findings from this trial, so this is summary of the key findings. For details of statistical analysis refer to the original papers, which are all available open access in the Evidence Based Mental Health journal:

Results from the young people in the trials show:

- A large minority of young people face mental health challenges (33% of 11-14 year olds reported significant social-emotional-behavioural problems and depressive symptoms);

- There was no evidence that the mindfulness training programme used was more effective than usual social and emotional teaching in helping young people’s mental health or well-being;

- Students’ engagement with the SBMT (school-based mindfulness training), that is to say home-practice, was low at post-intervention and the one year follow up;

- In the secondary outcome measures there were some differences between the two arms with young people in the trial arm reporting:

- Higher hyperactivity/inattention (post-intervention and 1 year follow up)

- Higher panic disorders and obsessive-compulsive scores (post-intervention)

- Lower levels of mindfulness skills (post-intervention)

- Higher teacher-reported emotional symptoms on the SDQ (1 year follow up only)

- There were no statistically significant differences between the SBMT (school-based mindfulness training) and the TAU (treatment as usual) arms on any primary or secondary outcome;

- Young people who were identified as ‘High-risk’ of mental health problems and were in the SBMT arm of the trial reported significant detrimental effects on risk of depression and wellbeing (post-intervention and at 1 year follow up);

- The mean number of session attended by students was 9/10;

- The young people had mixed views about the mindfulness training and many did not engage with the training.

The MYRIAD trial found no evidence that the mindfulness training programme used in schools was more effective than usual social and emotional teaching in helping young people’s mental health or well-being.

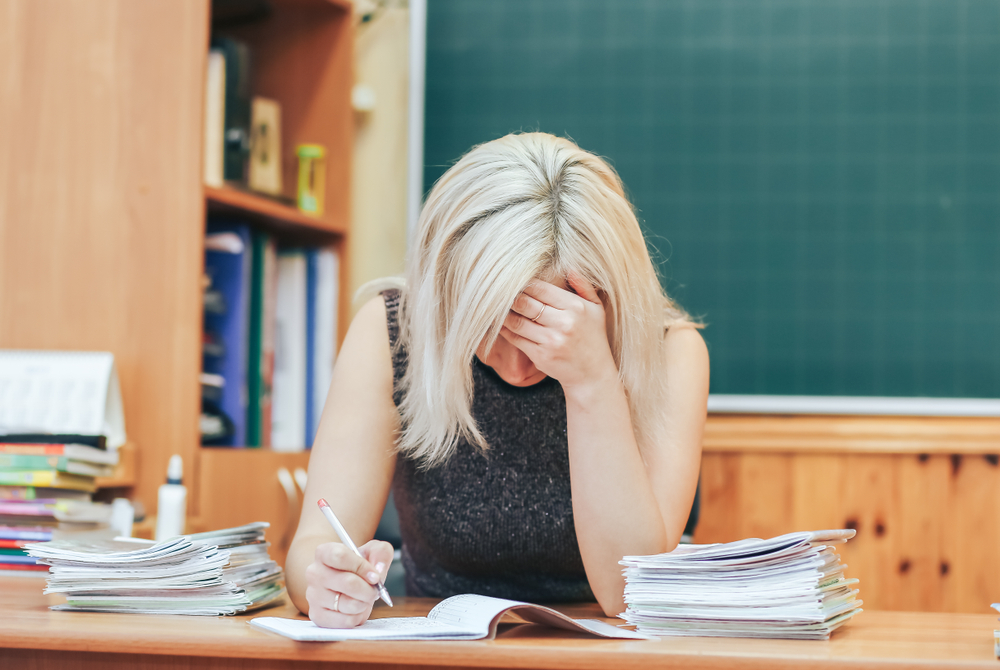

For teachers the outcomes were more positive, teachers in the SBMT arm reported:

- Greater student engagement (self-efficacy) following their teacher training, than those in the TAU arm;

- After delivering the curriculum to students, teachers reported less burnout (emotional exhaustion and lack of personal accomplishment);

- There was little evidence of a difference on other measures of mental health, perceived stress, self-efficacy, or mindfulness between teachers in the SBMT and TAU arms at either of these time points;

- After the Personal Mindfulness Training, teachers reported better school leadership and involvement;

- After the SBMT, teachers also reported a more respectful school climate;

- At the 1 year follow up only, the respectful climate scores remained significantly different to the TAU arm;

- 69% of teachers had continued to practise formal mindfulness at least occasionally at the one year follow up and 82% continued to practise informal mindfulness at least occasionally;

- Mean fidelity to the SBMT programme was 83.0% of the original content being taught;

- Mean quality in delivering the SBMT was 3.8 out of 6.

In terms of the economic impact, SBMT had a high probability of cost-effectiveness (83%) at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per quality-adjusted life year.

This research suggests that school-based mindfulness training can support changes in teacher burnout and school climate, but more work is needed to find out how best to sustain improvements over time.

Conclusions

The meta-analysis conducted as part of this research suggests that universal mindfulness based interventions delivered in schools may have some short-term positive benefits for mental health and wellbeing (e.g. improving symptoms of depression and anxiety) in young people. However, it appears that these findings are not sustained in the longer term. Of the 66 studies included in the meta-analysis, only a few were well designed adequately powered studies with a low risk of bias.

In light of the existing research, the MYRIAD trial provided a high quality, large scale study that demonstrates that a brief universal mindfulness intervention delivered to young adolescents does not appear to show that SBMT (school-based mindfulness training) has any greater impact on young people’s mental health than teaching as usual. It is, in fact, likely that for some young people who are at risk of developing mental health problems, it may worsen their scores on risk of depression and wellbeing.

It does seem however, that the effect of the mindfulness training on teachers was positive, improving their mental health. Mindfulness training also seems to impact the school climate, or at least the teachers’ perception of school climate.

Despite the findings this paper tells us a huge amount about the mental health of young people, the application of universal interventions, and the importance of high quality research.

The MYRIAD trial measured the possible adverse effects of school-based mindfulness training, and found that for some young people who are at risk of developing mental health problems, it may worsen their scores on risk of depression and well-being.

Evaluation

This high quality and adequately powered study has produced a null result for the main research question, which was to examine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a mindfulness training programme in schools compared with normal school provision.

The fact that a null result has led to the publication of a ‘special issue’ of a journal, however, reflects the importance of learning what can be taken from trials like this. In the first paper the authors reflect on the importance of optimising learning from large trials. If trials are based on sound theoretical underpinnings, we must consider not just finding evidence to support the theoretical model under investigation, but also how findings might drive future research. It’s vital that we collect a wide range of data so that a rich picture of events can be investigated, which can then support our learning. However, this will only happen if researchers are open and honest about their findings, report on all the data and manage expectations about a null result; so perhaps consider what to do in the event of a null or negative finding.

One of the biggest issues for research like this is the timescale that it takes; and this is something I have mentioned before in my forays in the woodland blogs. This research suggests that the mental health of our young people is getting worse and yet such high quality research takes such a long time to conduct and write up – this project being an example, taking 8 years from start to finish, a necessary but frustrating time scale. It is no wonder that small scale, poorer quality work has taken a lead, and school leaders and teachers, desperate to find cost effective, universal solutions to support the young people in their care are swayed by these results.

High quality research like the MYRIAD trial is always playing catch up with what is going on in practice in schools.

Implications for practice

For me this is where the MYRIAD trial comes into its own with a wide range of implications for practice in schools, further research and research practice itself.

First and foremost schools should consider whether universal mindfulness provision is a suitable intervention. The suggestion from this paper is that it makes little difference and can in fact make things worse for a small subset of at risk pupils. This highlights one of the challenges that schools face, they need to be seen to be doing something to support the young people within their community, but they are both time and cash poor. They do not have time to rigorously evaluate the evidence and high quality evidence is hard to access – behind paywalls and because it can be so jargon filled for non-specialists. It is probable that, even if teachers could access the research, they do not have the research literacy (most teachers’ degree background will not be in social sciences) to evaluate the research effectively. It is no surprise that they jump on simple, cash effective potential strategies even if the evidence is scant or poor quality, often trusting in external ‘experts’ who may have alternative motives. For the time being, schools should probably reflect hard on whether or not they should implement such universal mindfulness interventions. .

We need to reflect on this a little though – the trial took a specific age group and a specific training programme and robustly implemented it to reflect what it would look like in schools. With a high degree of certainty, we can therefore say that this particular universal mindfulness programme does not work on this age group as a whole, but may benefit some sub-groups and some young people not included (e.g. older children), or a different programme might work for example it may increase acceptability and effectiveness of the SBMT if it is co-designed with young people.

There is strong evidence that mindfulness skills are associated with better mental health, but young people need to practise these skills which requires buy-in from them. This paper suggests that we need a different approach to get the buy-in which will encourage young people to learn these skills and apply them in their lives. In the interim, schools should reflect hard on any universal intervention implemented and consider whether there is risk of harm and if so how they might identify any sub-group at risk. So the picture is complicated.

This research does throw out some really interesting ideas that schools could explore. Mindfulness does seem to work for teachers – of course there is a need for caution before headteachers rush off and buy in training for all staff, these staff chose to do the course and so it was not a universal support, but optional. It also suggests that the benefits of teacher mindfulness training filter down to the students through teacher wellbeing, classroom instruction and school climate. Further evidence from this research is also emerging that school climate is a really important factor in mental health and wellbeing of young people and is something that should be further explored.

The final paper in the series by Pim Cuijpers reflects on what we can learn about universal interventions from this trial. It is firstly clear that researching mental health interventions in a robust way is really challenging and when it is done well it is time consuming and has the potential to produce a null result. Secondly we need to be cautious when we implement universal interventions around mental health as it is possible that even when we shift the normal distribution towards the positive it is possible that for a sub-group the intervention may prove harmful – and I would argue that for schools to identify these potential risks is nigh on impossible.

Finally, and for me most importantly, researchers and psychologists need to support school leaders and teachers to understand research and its implications for practice. It is essential that research, even if it yields null results, is published and that we learn from it. It is commendable that this research has been made open access in the Evidence-Based Mental Health journal special issue.

Researchers and psychologists need to support school leaders and teachers to understand research and its implications for practice.

Statement of interests

Lucinda Powell was part of the Trial Steering Committee for the Myriad Project from 2018.

Links

Primary papers

Kuyken, W. et al & MYRIAD Team Group. (2022). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: the MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2021-300396

- Covers the primary outcomes of the trial with a focus on the impact on young people.

Kuyken, W. et al (2022). Effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision on teacher mental health and school climate: results of the MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300424

- Covers some of the secondary outcomes such as the impact of Mindfulness training on the teachers delivering it and the school climate as a whole.

Montero-Marin, J. et al. (2022). School-based mindfulness training in early adolescence: what works for whom, and how in the MYRIAD trial? BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300439

- Digs a little deeper into the results for some of the sub-groups of young people.

Other references

Axford, N., Berry, V., Lloyd, J., & Wyatt, K. (2022). How can we optimise learning from trials in child and adolescent mental health? BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300500

- Considers why and how we should research child and adolescent mental health.

Dunning, D. et al (2022). The impact of mindfulness training in early adolescence on affective executive control, and on later mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300460

- Compares the impact of mindfulness training compared to psychoeducation on ability to mitigate against mental health difficulties during periods of stress (in the case the Covid-19 pandemic).

Dunning, D. et al (2022). Do mindfulness-based programmes improve the cognitive skills, behaviour and mental health of children and adolescents? An updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300464

- Looks at the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on young people’s mental health.

Cuijpers, P. (2022). Universal prevention of depression at schools: dead end or challenging crossroad? [Editorial]. BMJ Evidence-Based Mental Health Editorial. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2022-300469

- Reflects on the learning from this trial in terms of the way forward for universal mental health interventions delivered in schools.

Psychology in the classroom podcasts

Lucinda Powell who wrote this blog has also recorded a set of #PsychologyInTheClassroom podcasts with the MYRIAD Project Lead Prof Willem Kuyken, talking about “mental health in schools”, and “mindfulness: what is it, how might it help children, teachers and schools?”. Highly recommended!

Photo credits

- Photo by Maxim Berg on Unsplash

- Photo by Yustinus Tjiuwanda on Unsplash

You might like to have a look at this response from the Mindfulness Initiative, a totally independent group with no links to MYRIAD or to the programme that produced the curriculum used. https://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org/myriad-response

our summary says

MYRIAD (My Resilience in Adolescence) was a large scientific study of mindfulness in schools. It is a highly significant and useful contribution to a complex emerging field, and there is much to learn from it. However, the simplistic and dismissive media headlines it produced initially were unfortunate and misleading. They do not reflect the study’s important positive findings for teacher burnout and school climate, which are vital for school wellbeing and effectiveness. They also do not reflect that, as the researchers say, the findings for students are ‘unexpected’ in view of the positive picture emerging from long-term research and need investigation – we suggest the necessarily novice nature of the teachers in the trial may help explain this. We very much support MYRIAD’s call for more systemic approaches to mental health and wellbeing in schools, and in this document we explore the nuances of the results and some possible context and explanations for the student findings.